Top Museum Acquisitions: 2017 in Review

A year’s worth of museum news is inevitably a mixed bag of good and bad. For instance, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City reported its largest ever number of visitors—seven million—but still found itself dealing with a $40 million deficit and causing the institution to delay the building of a new $600 million wing. On the other hand, in September, the struggling Danforth Art Museum in Framingham, Massachusetts, and its 3,000-object collection was taken over by the nearby Framingham State University and renamed the Danforth Art Center at Framingham State University. Those who had donated money and objects to the former museum might be upset at the change of direction and ownership, but presumably an art space is better than no art space. Something or nothing was the argument made by the director and trustees of the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which decided to sell a group of its most prominent artworks—including prized pieces by Norman Rockwell, Frederic Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Alexander Calder—to augment the institution’s endowment and refocus the museum’s basic mission from an art museum exclusively to a museum of science, history and the arts. Public outcry has resulted in an injunction through January 29, 2018.

|

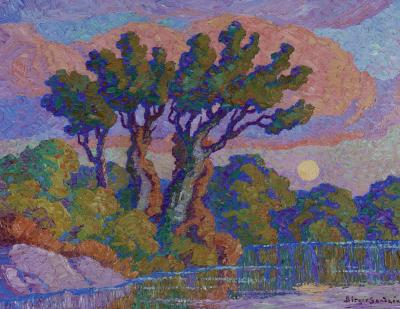

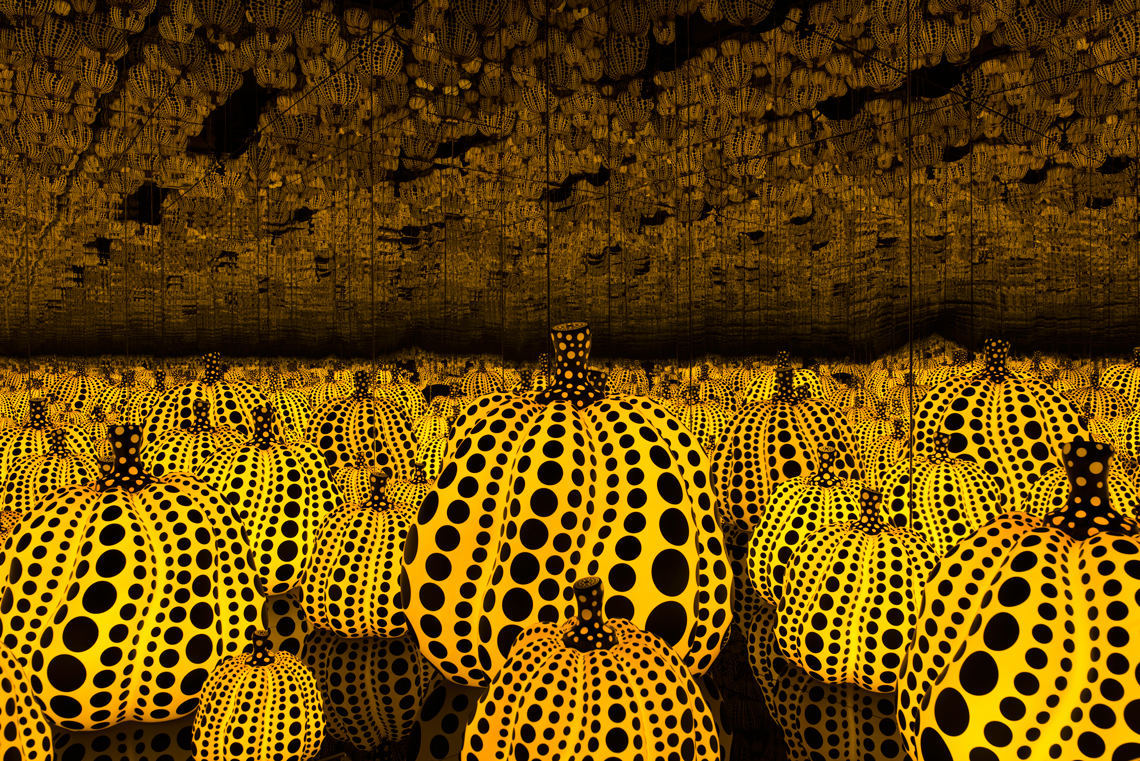

| Fig. 1: Yayoi Kusama (b. 1929), All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins, 2016 Wood, mirror, plastic, acrylic, LED. Courtesy Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / Singapore and Victoria Miro, London. © Yayoi Kusama, pending joint acquisition of the Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through TWOxTWO for AIDS and Art Fund. |

Despite rising museum costs, existing institutions continue to expand and new museums continue to open. Among the former, in Sarasota, Florida, the Ringling Museum’s Kotler-Coville Glass Pavilion, opening in January 2018, will house their growing studio glass collection; the New Museum in New York’s Bowery announced that Shohei Shigematsu of OMA will design their expansion; and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles will add 40,000 square feet by 2020. New museums include the Magazzino in Cold Spring, New York, focusing on contemporary Italian artwork; the Marciano Art Foundation in Los Angeles, which Paul and Maurice Marciano (founders of Guess jeans) will fill with their collection of contemporary art; and the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art, which the actor and comedian plans for Los Angeles in the near future. After facing opposition in San Francisco and Chicago, “Star Wars” filmmaker George Lucas received the go-ahead from Los Angeles city officials to build a Museum of Narrative Art, based on his collection of illustration, fantasy, and comic book art.

Curators and directors of institutions continually want to add to their permanent collections, either through the generosity of donors or by using specified funds. The following are just some of the material acquired during the past year.

In 2017, contemporary art was celebrated by purchases at many institutions, including New York’s Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), which continued its commitment to supporting contemporary craft through the acquisition of thirty-nine objects from established and emerging artists. Newport Beach, California, real estate developer Gerald E. Buck donated to the University of California at Irvine his 3,200-piece collection of modern and contemporary artworks, valued at tens of millions of dollars, by artists associated with the state, including Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, Joan Brown, Gilbert “Magu” Lujan, and Sam Francis.

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms (Fig. 1) employ the repeated use of objects and paintings in an environment of mirrors that induce a hallucinogenic experience. The Dallas Museum of Art now has the only Infinity Mirror Room, featuring polka-dotted pumpkins, of its kind in a North American collection, from a pending joint acquisition with the Rachofsky Collection and the Dallas Museum of Art through TWOxTWO for AIDS and Art Fund. American sculptor and furniture maker John Cederquist also likes to trick the eye. He uses elaborate inlays and airbrush paint techniques to create cabinets, chairs, and other items that appear to be something else. From a distance, his 2010 Double Fuji cabinet (Fig. 2) looks like a kimono, but is an actual working cabinet; it now belongs to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Among LACMA’s other acquisitions was a joint purchase with the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens of two prototype chairs (1979–80) by American artist Donald Judd. The two institutions will share ownership of these pieces. The Huntington's Art Collectors' Council purchased two paintings for the museum: Albert Herter’s Woman with a Fan (ca. 1895), and Bathers (Bath Houses) by realist painter George Tooker, the first example of the artist's work to join a museum collection in the western United States.

|  | |

| Fig. 2: John Cederquist (b. 1946), Double Fuji cabinet, 2010. Various woods, aniline dyes, epoxy resins. Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Gift of the 2017 Decorative Arts and Design Acquisitions Committee (DA²) with Suzanne and Ric Kayne. © 2017 John Cederquist, photo by Gary Zuercher, courtesy of the artist. | ||

2.jpg) | .jpg) |

| Left: Donald Judd (1928-1994), Prototype Desk and Chairs, 1978-1980. Donald Judd Furniture © 2017 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; joint acquisition between the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and The Huntington Library, Art Collection, and Botanical Gardens. Right: George Tooker (1920-2011), Bathers (Bath Houses), 1950. Egg tempera on gessoed board, 20 3/8 x 15 3/8 inches. Courtesy The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Web exclusive: These two images have been added to the online version of this article. |

| |

| Fig. 3: Miniature painted chest, Grayson County, Virginia, 1825-1850. Inscribed on the inner lid: “William, M, Mitchell / Was born Sept. the 1st 1825.” Tulip poplar and paint. H. 10½, W. 17, D 9 in. Anne P. and Thomas A. Gray Southern Decorative Arts Purchase Fund (5898). Courtesy MESDA. Mitchell (1825-1888), a minister, physician, farmer, and member of the Virginia infantry, saw action under General Stonewall Jackson. |

A significant group of early colonial American furniture received by the Philadelphia Museum of Art from collectors Anne and Frederick Vogel III is installed in an exhibition in the museum’s American galleries. The Seminarians, a Boston-based collector group, purchased and gifted a Campeche chair to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, acquired a miniature painted box (Fig. 3) with the name of the original owner and his birthdate (on the inside). It is the only example from a recently discovered group (previously attributed to Pennsylvania) with identifiers, securely placing the box and the group in southwestern Virginia. MESDA also acquired a pair of rare North Carolina fraktur (Fig. 4) that are not only visually arresting, but relate to the family of craftsmen responsible for the architecture in two of MESDA’s galleries. Moreover, Noah A. Moose, the artist, was also a tailor, which perhaps explains the exuberant clothing. Other acquisitions included a chest of drawers signed by furniture maker Karsten Petersen, making it the Rosetta stone for identifying his work.

Longtime patrons Charles and Valerie Diker, promised ninety-one examples of important Native American art to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which will be integrated into the American Wing. Toledo Museum of Art’s Georgia Welles Apollo Society made possible the acquisition of three significant Native American works: an Acoma embroidered manta (circa 1850, one of only thirty-five known); a Cheyenne tipi; and a Santa Domingo Pueblo polychrome clay jar (Fig. 5).

| |

| Fig. 4: Noah A. Moose (1817-1874), one of a pair of fraktur for the Sigman and Bost Families, Catawba County, North Carolina,1840. Watercolor and ink on paper, 13 x 15 inches. Courtesy MESDA Collection; Gift of Betty and Jim Becher and the MESDA Purchase Fund ( 5919.1-2). |

The Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame now has a pair of porcelain Monteiths—crenelated vessels used for cooling wine glasses—from 1861, acquired through a decorative arts purchase fund. The Cleveland Museum of Art purchased a group of Nabeshima porcelain, the finest Japanese porcelain ever produced and representing the pinnacle of Japanese aesthetics in the medium. One of the dishes, with ginkgo leaves, was made for the Shogun in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and his retinue (Fig. 6).

Though not recent acquisitions, some items are being reintroduced. This past year, following renovations at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, three hundred objects— including examples of American silver and Chinese export porcelain from the George Washington Memorial Service—were brought up from storage to the museum’s 3,275 square-foot decorative arts gallery, while the New Orleans Museum of Art, following its renovations, is highlighting selections from its collection of glassware, furniture, lamps, and other decorative pieces.

The Cleveland Museum of Art, one of the many museums seeking to expand their permanent collections in African-American art, purchased Norman Lewis’ 1960s Alabama, and was given Robert Colescott’s 1980 Tea for Two (The Collector) by Agnes Gund. In early December, the McNay Art Museum announced three major acquisitions, all collages, by African-American artists Benny Andrews, McArthur Binion, and Rashaad Newsome. The Saint Louis Art Museum received eighty-one works by contemporary African-American artists, including Stanley Whitney’s 1992 Out in the Open, from Ronald Maurice Ollie and wife Monique McRipley Ollie. The Baltimore Museum of Art added to its growing collection of works by African-American artists, with Mark Bradford’s 2016 mixed-media painting My Grandmother Felt the Color (purchased through anonymous donations) and the 2005 video Niagara (gift of the artist), also Autumn Flight (1956) by Norman Lewis (gift of several donors and acquisition funds).

|  |

| Left: Stanley Whitney (b. 1946), Out in the Open, 1992. Acrylic on canvas, 53 1/2 x 60 inches. Courtesy Saint Louis Art Museum; the Thelma and Bert Ollie Memorial Collection (E14521.79). © Stanley Whitney. Right: Norman Lewis, Autumn Flight, 1956. Autumn Flight is an exemplary painting by the influential artist. It evokes a flock of birds moving through a mottled autumnal sky, referencing the natural world through the artist’s signature brand of abstraction. The paint was applied to the canvas in several layers by brushing and spraying, either directly or with the use of a sharp stencil. Courtesy Baltimore Museum of Art. Web exclusive: These two images have been added to the online version of this article. |

|  | |

| Fig. 5: Polychrome pottery jar, Santo Domingo Pueblo, 1865-1875. Native clay, pigment, 19 x 16 in. Courtesy Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, Ohio); Gift of The Georgia Welles Apollo Society (2017.16). | Fig. 6: Dish with Ginkgo Leaves. Japanese, Edo period (1615–1868), Genroku era (1688−1704). Porcelain with underglaze blue (Hizen ware, Nabeshima type). Diam. 8 in. Courtesy The Cleveland Museum of Art. The complex, abstracted design of ginkgo leaves and “Chinese grasses” (karakusa) is among the most interesting of the underglaze blue designs of its era. This type of dish was produced in sets of five and used along with sake cups for dining services. |

|  | |

| Fig. 7: Thornton Dial (1928-2016), Shack Town, 2000. 92 x 76 x 70 inches. © Estate of Thornton Dial. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio. Courtesy New Orleans Museum of Art. | Fig. 8: Jessie T. Pettway, Bars and String-Pieced Columns, ca. 1950s. Cotton, 95 x 76 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Museum purchase, American Art Trust Fund, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection. Artwork: © 2017 Jessie T. Pettway / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. |

The High Museum of Art in Atlanta purchased Kara Walker’s fifty-eight- foot-long cut-paper silhouette installation The Jubilant Martyrs of Obsolescence and Ruin (2015), and acquired fifty-four works by thirty-three contemporary African-American artists from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, a nonprofit organization whose aim since 2010 has been to expand the recognition of leading contemporary African-American artists in the Southeast through support for exhibitions, programs and publications. In 2014, the Foundation began a program to transfer its collection to leading American and international museums. Another beneficiary of the Foundation’s gift-purchase arrangements in 2017 was the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF), which acquired sixty-two works of art made by twenty-two African-American artists, which are currently in an exhibition that runs through April 2018 (Fig. 8); the New Orleans Museum of Art (Fig 7) and the Ackland Art Museum were also in receipt of the foundation’s collections, with the acquisition of ten and twelve works respectively.

The Whitney Museum of American Art was given a 1932 Edward Hopper painting, City Roofs (Fig. 9), by an anonymous donor, as well as a wealth of archival materials from the Arthayer R. Sanborn Hopper Collection Trust. The Huntington Museum of Art in Huntington, West Virginia, acquired a rare English Chinoiserie sugar and tea caddy set by Royal goldsmith Thomas Heming (1722–1801) (Fig. 10). The Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, acquired Portrait of the Art Dealer Heinrich Thannhauser by Lovis Corinth (1918). Corinth was an artist revered as a critical figure in the history of German expressionism; in 1904, his sitter founded Moderne Galerie in Munich, which was at the forefront of the art scene. Also entering the collection was Head (circa 1913), one of less than thirty sculptures carved by Amedeo Modigliani (Fig. 11).

|

| Fig. 9: Edward Hopper (1882–1967), City Roofs, 1932. Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Promised gift of an anonymous donor (P.2016.11). © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by Whitney Museum of American Art. The painting depicts the rooftop of Hopper’s Greenwich Village studio, which he maintained for more than 50 years. |

| |

| Fig. 10: Three-piece sugar and tea caddy set by Royal goldsmith Thomas Heming (1722–1801), England, 1757. Silver with original fitted box. Photo by John Spurlock. Courtesy The Huntington Museum of Arts, Huntington, West Virginia. |

A work by French artist François-Pascal-Simon Gérard (1770-1837) enters The Frick Collection in New York (Fig. 12). The full-length portrait of Prince Camillo Borghese, the brother-in-law of Napoleon Bonaparte, is the museum’s most important painting acquisition since 1991 and will be part of an exhibition opening in October 2018. With the passing of banker and art collector David Rockefeller in March, a promised gift of Camille Pissarro’s 1868 oil Landscape at Les Pâtis, Pontoise (Fig. 13) entered the collection of the National Gallery of Art, bringing to sixty-seven the number of works by the artist in the museum’s permanent collection.

Longtime benefactors Peter and Paula Lunder saw that they could make a transformative difference at Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, through their gift of 1,150 artworks, estimated at more than $100 million, by 150 artists, among them, Mary Cassatt, Albrecht Dürer, Vincent Van Gogh, Jasper Johns, Maya Lin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Claes Oldenburg, Rembrandt Van Rijn, James McNeill Whistler, and Ai Weiwei.

|  | |

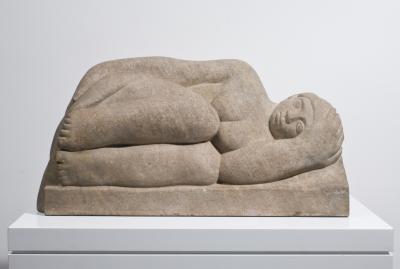

| Fig. 11: Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), Head, ca. 1913. Limestone, 20⅝ x 9¾ x 14¾ in. Courtesy Kimbell Art Museum; Given in honor of Ted and Lucile Weiner by their daughter Gwendolyn (2017). | Fig. 12: François-Pascal-Simon Gérard (1770–1837), Camillo Borghese, ca. 1810. Oil on canvas, 83⅞ x 54¾. Courtesy The Frick Collection, New York. |

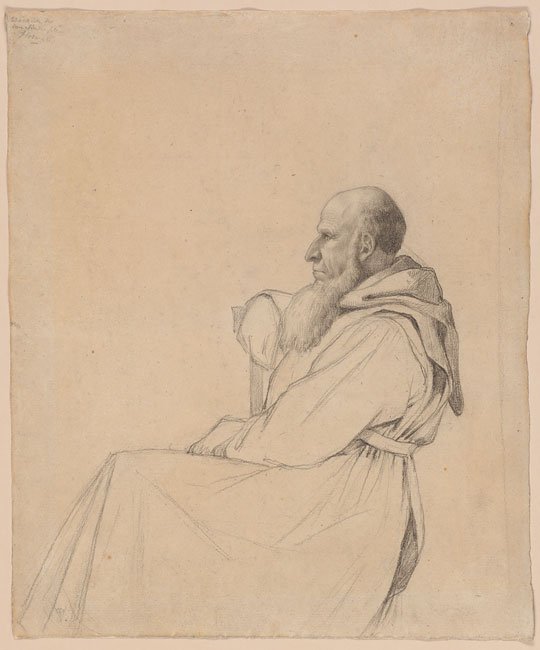

The Morgan Library & Museum added a drawing by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (Seated Camaldolese Monk, 1834, gift of Jill Newhouse), Martin Schongauer’s Death of a Virgin (ca. 1470s), and works by David Hockney and Martin Puryear, the latter two acquired through purchase funds. The Meadows Museum, which oilman Algur Meadows founded at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, in 1962 to house his collection of Spanish art and which received an additional $45 million gift two years ago from the Meadows Foundation, purchased an early fifteenth-century altarpiece attributed to Catalonian painter Pere Vall. The gilded tempera on wood panel features Saints Benedict and Onuphrius. This painting is one of only six extant panels that once formed the bottom row of an altarpiece in one of Catalonia’s many churches (two others are in the collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art).

|  |

| Left: Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), Seated Camaldolese Monk, 1834. Graphite on paper. Courtesy The Morgan Library & Museum; Gift of Jill Newhouse. Right: Pere Vall (Spanish, active ca. 1400–c. 1422), Saints Benedict and Onuphrius, ca. 1410. Tempera on Softwood Panel. Courtesy Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas; Museum Purchase with funds generously provided by Richard and Luba Barrett (MM.2017.01). Photo by Kevin Todora. Web exclusive: These two images have been added to the online version of this article. |

A donation of 113 Dutch and Flemish Golden Age works (Fig. 14) by seventy-six artists (including Rembrandt, Rubens, Gerrit Dou, Frans Hals, Albert Cuyp and Jan Steen) from collectors Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo and Susan and Matthew Weatherbie to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is intended to be shared with wide audiences and help nurture the next generation of scholars and curators. To support this intention, the donors made a substantial gift of funds to establish a Center for Netherlandish Art at the MFA, and the museum is committed to displaying and lending the collections generously. This center is the first of its kind in the United States; its programs are expected to launch in 2020.

|

| Fig. 13: Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), Landscape at Les Pâtis, Pontoise, 1868. Oil on canvas, 31⅞ x 39⅜ inches. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Gift (Partial and Promised) of Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art. |

|  | |

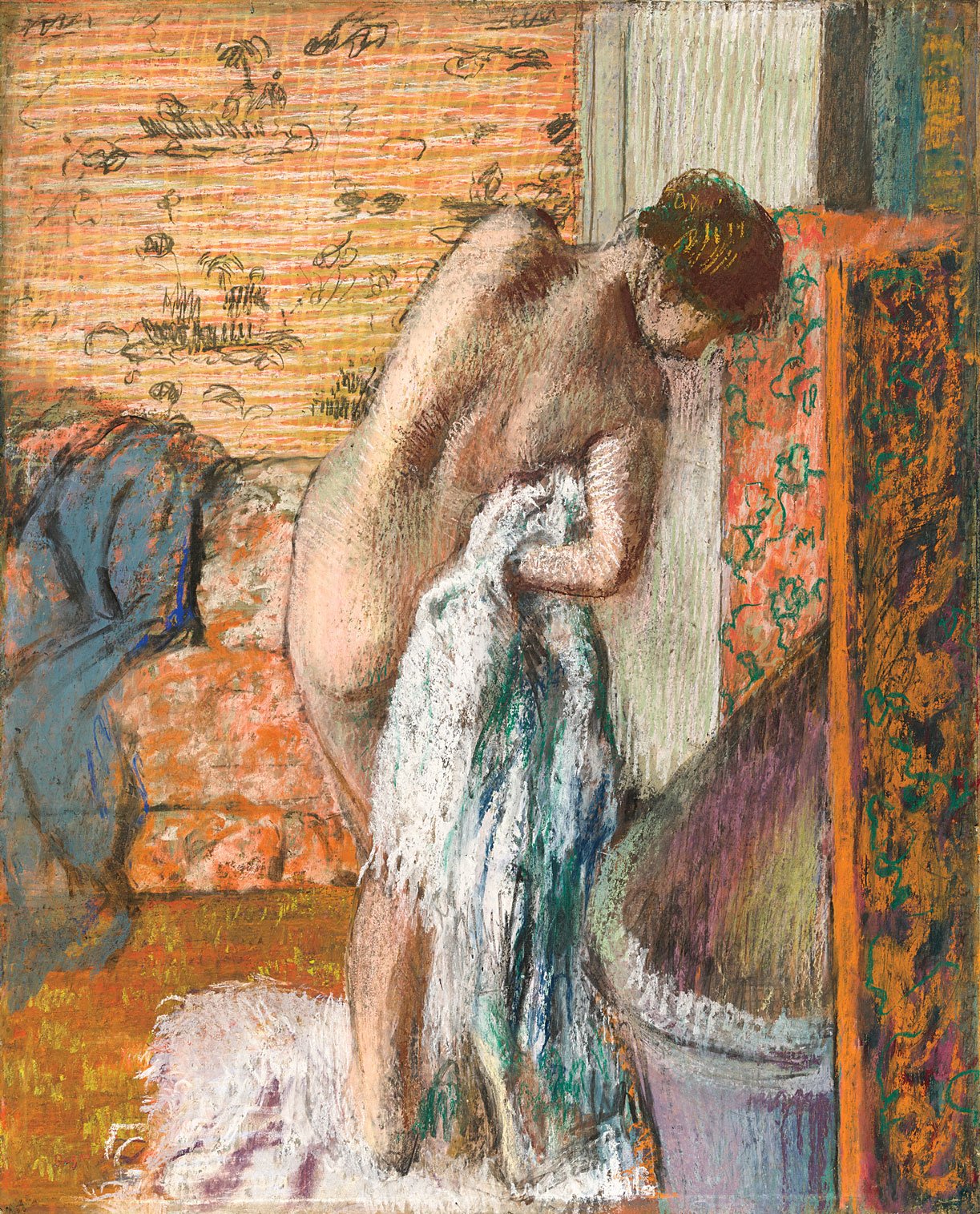

| Fig. 14: Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669), Portrait of Aeltje Uylenburgh, 1632. Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Collection. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. | Fig. 15: Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917) After the Bath, ca. 1886. Pastel on paper, laid down on board, 72 x 58 cm. Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Trust. |

The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles made what it referred to as “one of the most spectacular acquisitions in its history,” with sixteen drawings (Fig. 15) by such artists as Michelangelo, Lorenzo di Credi, Andrea del Sarto, Parmigianino, Rubens, Barocci, Goya, and Degas, as well as a 1721 painting by Jean Antoine Watteau (The Surprise) and Parmigianino’s circa-1535 The Virgin and Child with Saint Mary Magdalen and the Infant Saint John the Baptist. The Getty bought the latter in 2016 for £24.5 million from the Dent-Brocklehurst family of Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire. An export license was not granted for eight months while the British government sought, and failed, to find institutional buyers to match the price. The Getty also received from Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser 386 works by seventeen different photographers, including Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunningham, William Eggleston, Andreas Feininger, and Dorothea Lange.

Sometimes, permanent collections are impermanent. In 2017 the Boston Public Library was required to return to the Italian government two fifteenth-century illustrated religious manuscripts stolen from its owners in Sicily. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also returned to the Italian government a 2,300-year-old Greco-Roman vase looted from a tomb in Italy in the 1970s. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston reached an out-of-court settlement with the estate of Emma Budge, allowing the institution to keep seven pieces of eighteenth-century German porcelain sold under Nazi duress in Berlin in 1937. And then, some acquisitions make worldwide headlines for other reasons, such as when the United Arab Emirates (identified as the purchaser after much speculation) acquired Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, for $450 million. The painting will be on view at the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

Daniel Grant is a freelance writer specializing in the arts industry.

This article was originally published in the 18th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.