Upholstery CSI: Reading the Evidence

|

| Fig. 1: Sofa, London, England, ca. 1760. Mahogany and beech. Museum purchase (1963-191). The reproduction upholstery visually equates the sofa’s original appearance. See figure 12 for details as to upholstery techniques. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. |

In the eighteenth century, a chair or sofa’s upholstery, including both the show material and foundation, constituted a major portion of its value. The expense lay in the high price of the materials, especially the wool or silk show cloth, and the upholsterer’s labor. The various techniques used by the upholster required extensive hand stitching to create the high, low, rounded, boxed, or angled profile as well as any loose mattresses (long sofa cushion), bolsters, or cushions (Fig. 1). When the foundation remains on a piece of seating furniture, the upholsterer’s original intent for the chair or sofa’s appearance is clear. But when these soft fabrics are missing, then curators, collectors, and conservators become detectives.

Understanding the techniques in an upholsterer’s tool box is essential for being able to read the evidence on a bare frame. To achieve softly rounded profiles, stuffed rolls were stitched and nailed along the edges of seats, backs, and arms (Fig. 2). Sewing through the stuffed roll to create a stitched roll provided a more rigid edge (Fig. 3). And a web or canvas-raised edge provided a stiff, boxy profile (Fig. 4). The center of the seat or back, whether or not it contained a roll or edge on one or more faces, was filled with loose stuffing that provided the softness and loft contained by the top linen and then covered with show cloth (woven textile or leather). Alternative choices of stuffing materials, from curled hair to straw to rush, added to the upholsterer’s effects, as did wooden blocks and peaks positioned at the corners to support the profile shape, and the quilting or tufting that helped to keep the loose stuffing in place while also adding a decorative effect. Additional techniques like raised stitched pads could be used where wooden blocks and peaks were not in evidence. Tapes, welting, fringe, tassels and decorative nails rounded out the upholsterer’s decorative tools.

|  | |

| Fig. 2: Easy chair, England, 1750-1760. Mahogany, beech, deal; linen, iron tacks, hair and straw stuffing, and wool fragments. Gift of Edward T. Lacy (1986-267). The original upholstery on this easy chair includes the stuffed roll on the wing crest that provides the softly rounded profile to the upholstery foundation. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. | Fig. 3: Back stool, England, ca. 1765. Walnut, oak; linen, iron tacks, hair stuffing, and silk threads. Museum purchase (1982-188). Stitching through a stuffed roll creates a more rigid edge. This example has come loose from the front seat rail of the chair. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. | |

|  | |

| Fig. 4: Upholstery conservator Leroy Graves stitches a web-raised edge on the seat of a reproduction back stool. The use of webbing along the edge combined with an integral stitched roll creates an angular, boxy, rigid edge for the upholstered seat. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. | Fig. 5: Armchair, Norfolk, Va., 1790–1810. Mahogany and ash. Gift of the Sealantic Fund (1988-390, 1). Modern brass nails partially inserted into the original holes show the box-and-swag decorative pattern used on the seat rails of this armchair. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. |

When all soft materials are missing from a seating frame the only evidence of what they were and what foundation element they created includes nail holes, corrosion residue in the holes, parts of nails, impressions from materials or tacks, and possibly threads or larger bits of fluff left under a nail or in a hole. Clusters of nail holes on top of the seat rails might indicate where webbing strips were nailed; an uneven row of nail holes across the upper half of a rail might suggest the attachment of the linen used in a stuffed or stitched roll; decorative patterns or rows of holes might indicate the use of brass nails (Fig. 5).

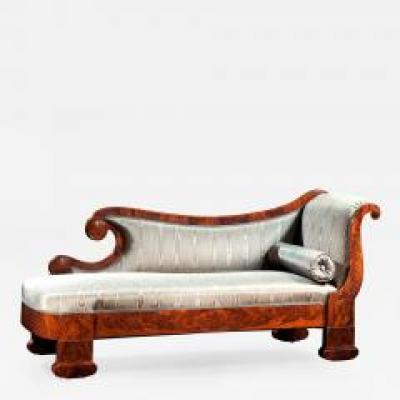

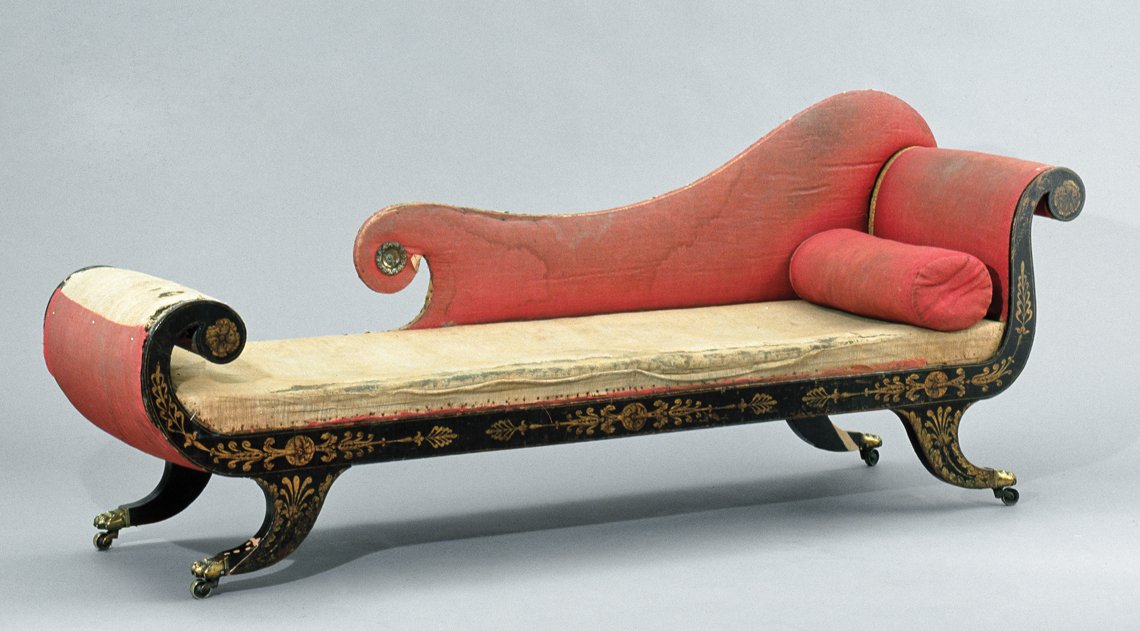

When much of the original upholstery survives on a piece like the circa-1820 Baltimore painted couch (Fig. 6), it is possible to detect upholstery changes at the macro level. The couch survived with all of its foundation, much of its original red worsted show cloth, and its original bolster intact. When looking at the back, there is a cleaner diagonal section of fabric visible that aligns with the bolster and scrolled head of the couch; a clue that something, now missing, protected that area from soiling. Like other Grecian couches of the period, this example originally had a cushion, which when laid over the bolster, covered that diagonal section of the back (Fig. 7).

|

| Fig. 6: Couch, attributed to Hugh Finlay, Baltimore, Md., 1819–1821. Tulip poplar, paint, and brass; linen, iron, hair stuffing, wool, and silk. Museum Purchase, Acquisition funded by Bridget and Alfred Ritter in honor of Milly McGehee and Deanne Deavours (2003-1, 1). Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. |

|

| Fig. 7: Couch shown in figure 6 but with reproduction upholstery and replacement pillow. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. |

|  | |

| Fig. 8: Back stool, England, ca. 1765. Mahogany, beech; linen, canvas, straw and hair stuffing, leather, wool threads, brass, and iron. Museum Purchase (1980-186). Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. | Fig. 8a: Front corner of figure 8, showing the top section of the leg that was left uncut. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. |

In the case of a circa-1765 English leather back stool with a Maryland history, the slumping of the boxy back profile and the alterations to the seat’s foundation tell us that the original upholsterer took short cuts in his construction that caused the upholstery to fail (Fig. 8). A chair with a boxy upholstery profile like this should have a web or canvas-raised edge around the seat and back to provide the structure and support to the foundation. This chair lacks that element. The upholsterer skipped the important steps of cutting the square blocks (which the chairmaker would have left for purposes of shaping by the upholsterer) into triangular peaks and creating rigid stitched rolls inside the canvas edges (Fig. 8a). Without the rigidity of the stitched rolls, the side and particularly the front edges of the seat failed, thus causing the seat’s loss of its leather show material and subsequent changes to its foundation. Did the upholsterer make a rookie mistake or consciously choose to save time and money by cutting corners? We will never know. But if the English upholsterer knew that his chair was being ordered from faraway Maryland, he may have thought that he could get away with shoddy workmanship. Colonial clients, including George Washington, did complain about the costs and workmanship of English goods, but it is unclear how often their concerns were satisfactorily addressed.1 A Philadelphia armchair attributed to Thomas Affleck with a history of ownership in the Penn family illustrates how the edges of a properly upholstered boxy seat should appear (Fig. 9).

When a chair survives in only its bare frame, the search for evidence is far more difficult than when some or all of the textiles survive in place. The myriad of nail and tack holes in a circa-1760 Williamsburg, Virginia, easy chair made in the Anthony Hay shop (Fig. 10) may initially seem impossible to decipher, but a closer examination of the holes allows us to identify where webbing strips and linen were tacked to the frame. This evidence supports the use of stuffed rolls along the front of the seat rail, the curved elements of the wings, and the crest (top of the back). These stuffed rolls combined with the chamfer on those upper elements of the frame would have provided a softly rounded profile for the back and arms of the chair.

|  |  | ||

| Fig. 9: Armchair, attributed to Thomas Affleck, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany and white oak. Museum purchase (1930-170). Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. | Fig. 10: Easy chair, attributed to the Anthony Hay shop, Williamsburg, Va., 1750–1770. Mahogany, ash, yellow pine, tulip poplar; iron, linen (fragment). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Vernon M. Geddy, Jr. (1989-372). Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. | Fig. 11: Reproduction easy chair, Leroy Graves, Williamsburg, Va., 2003. Mahogany, yellow pine, ash, tulip poplar (R2005-97). Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. |

|

| Fig. 12: “Deconstructed” sofa illustrated in figure 1. Although this sofa looks like it was upholstered using traditional methods, senior conservator of upholstery, Leroy Graves, created a nonintrusive upholstery system to replicate the original appearance. The system gives the look of the traditional upholstery without adding new nail holes and thus damage to the frame. The system is fabricated with conservation safe materials such as Ethafoam, copper, epoxy-infused linen, and plastic covered in a reproduction silk damask. Courtesy the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. |

Distinguishing iron tack holes from brass nail holes can be as simple as seeing a line of perfectly spaced holes, impressions of the round heads, or even finding a hole with a brass nail shank remaining. This easy chair had a very large number of brass nails ornamenting it that were utilitarian as well as decorative. A green corrosion product was discovered in these brass nail holes indicating that they were used with leather. The corrosion product is due to the chemical reaction of the brass and the acids in the tanned leather hides. Leather upholstery was often nailed to the frame in places where textiles might have been seamed. Brass nails were often used to secure the leather in these locations and hide the joints. The location and number of brass nail holes on this chair combined with the green corrosion product indicate that the chair was originally upholstered in leather. It would have looked identical to this reproduction easy chair that was upholstered in leather using the traditional methods indicated on the antique frame (Fig. 11).

Once the evidence is read, a conservator can reconstruct the original appearance of an upholstered seat using nonintrusive methods and conservation safe materials. A circa-1760 London sofa upholstered in reproduction blue silk damask illustrates how the nonintrusive treatment pioneered by Senior Conservator Leroy Graves at Colonial Williamsburg recreates the original intent of the maker without further damaging the frame as would traditional nailed-on upholstery (Fig. 12).

Upholstery CSI: Reading the Evidence at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum at Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, opens on May 26, 2018, and runs through December 2020. The upholstery evidence included in this article is based on research by Leroy Graves and published in his book, Early Seating Upholstery: Reading the Evidence (2015).

Tara Gleason Chicirda is curator of furniture at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Leroy Graves is senior conservator of upholstery at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

All images courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.