For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design

Founded in 1825 by Samuel F. B. Morse and a group of forward-thinking fellow artists, the National Academy of Design has a simple yet powerful mission: to provide means for the training of artists and to promote and exhibit their art. Since its founding, the Academy has upheld a rule from its first constitution and by-laws: every elected National Academician (NA) must donate a work to the Academy’s collection, in keeping with the conventions of the royal academies of art in France and England. In 1839, the Academy’s governing council decided that all individuals nominated to the preceding rank of Associate National Academician (ANA) must also present a portrait of themselves for the collection, whether painted by their own hand or that of a fellow artist. Such gifts of “diploma works” and “diploma portraits” are the defining feature of the Academy’s collection and the conceptual spine of the exhibition For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design, a collaboration between the American Federation of Arts and the National Academy of Design. The exhibition offers an unprecedented glimpse into the ways a group of American artists have defined themselves and their painted worlds through the past two centuries.

By presenting academicians’ two diploma submissions side by side, the exhibition outlines a unique story of American art from the 1800s to the present day written by its makers—an artists’ art history, so to speak. The installation also demonstrates academicians’ painterly concerns and visual experimentation across time by pairing paintings that would otherwise be relegated to separate movements or epochs. Additionally, responses to works by current NAs as well as a distinguished roster of scholars, recorded in the accompanying catalogue alongside the paintings that inspired them, form another pairing of sorts.

|

|  | |

left: Ferdinand Thomas Lee Boyle (1820–1906), Eliza Greatorex, 1869. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25¼ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; ANA diploma portrait, presentation date unknown (145-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. right: Will Barnet (1911–2012), Self-Portrait, 1981. Oil on canvas, 31⅛ x 45½ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; ANA diploma presentation, April 6, 1981 (1981.630). | ||

Eliza Greatorex (1820–1897) may be lesser known today, but in her lifetime, she achieved a remarkable degree of success for her graphic work, which she frequently exhibited at the Academy’s annual exhibitions. She even travelled the American West in 1873 in search of inspiration—an extraordinary feat for a woman artist of the time. As a pupil of Henry Inman (1801–1846) and a sought-after portraitist, Boyle was a natural choice to render Greatorex’s likeness. Will Barnet is now widely regarded as a leading modernist, known for the economical facture of his painted forms. Though separated by 112 years, both artists are depicted in their Academy portraits with stylus and sketchbook ready at hand. The pairing reveals timeless truisms: painting is a mode of inhabiting the world, mark making a way of recording all that and more.

|

|

William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), The Young Orphan [or] An Idle Moment [or] Portrait, 1884. Oil on canvas, 44 x 42 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, November 24, 1890 (221-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. |

|  | |

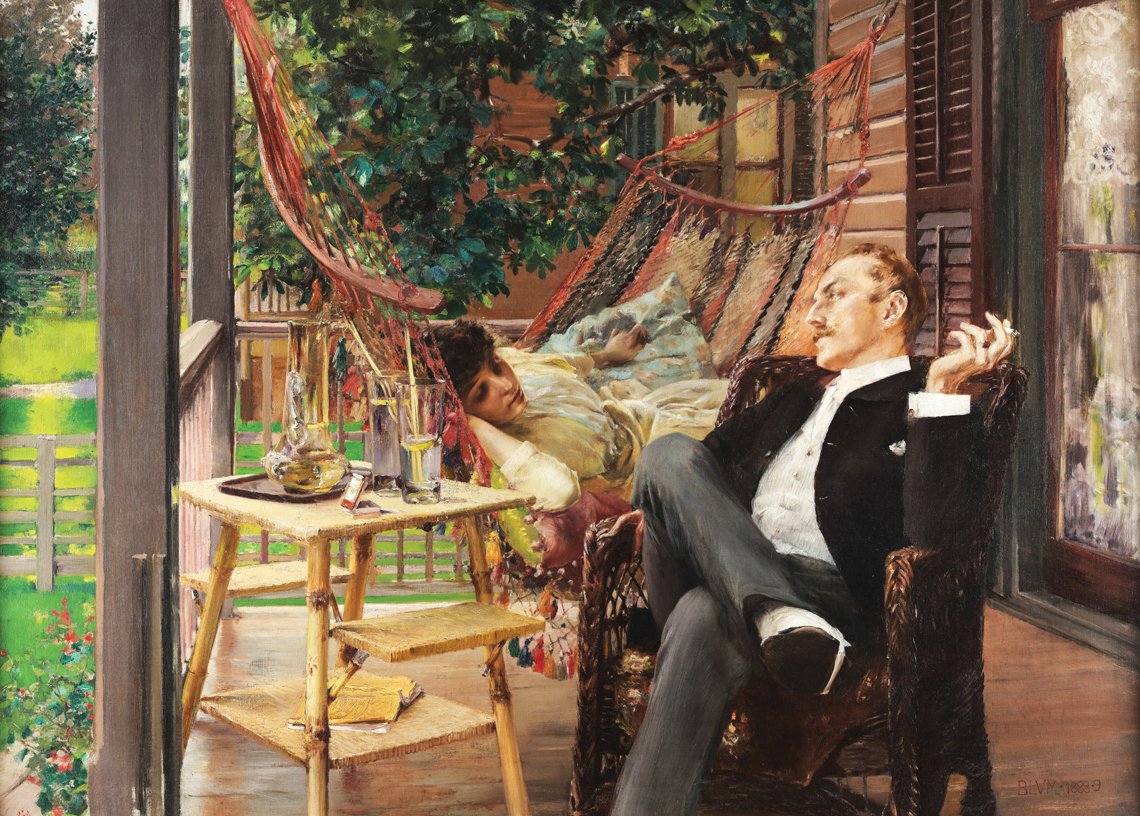

left: William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), Robert Blum, 1888. Oil on canvas, 21⅛ x 17⅛ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; ANA diploma presentation, March 18, 1889 (228-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. right: Robert Frederick Blum (1857–1903), Two Idlers, 1888–89. Oil on canvas, 29 x 40 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, March 26, 1864 (108-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. | ||

Blum and Chase were intimate friends: the two traveled throughout Europe together in the first half of the 1880s, frequently depicted one another, and were elected ANAs in the same year. The Young Orphan (above) likely depicts a model Chase found at the Protestant Half-Orphan Asylum, near his studio in New York City, while Two Idlers pictures the prominent painter William Jacob Baer and his musician wife, Laura Schenk, lounging at their home in Brick Church, New Jersey. Although he is beloved today, many of Chase’s critics perceived an aloofness in his figures—some even going so far as to claim his work “never sounded those notes that come from the depth of the human heart.” 1 The emotionally stirring portrait of Blum forges a deeper connection between the duo’s well-known works.

|

|

George Bellows (1882–1925), Three Rollers, 1911. Oil on canvas, 39⅝ x 41¾ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, December 1, 1913 (79-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. |

|  | |

left: Reuben Tam (1916–1991), Monhegan Landform, 1974. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; ANA diploma presentation, October 1, 1986 (1986.214). (c) Estate of Reuben Tam. Courtesy American Federation of Arts. right: Robert Henri (1865–1929), George Wesley Bellows, 1911. Oil on canvas, 32 x 25⅞ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; ANA diploma presentation, December 4, 1911 (561-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. | ||

Bellows, a student of the influential teacher Robert Henri, painted this seascape (above) during a trip the two took together in the summer of 1911 to Monhegan Island, fifteen miles off the coast of Maine. That same year, Henri depicted Bellows in the latter’s Academy portrait. Like Henri and Bellows before him, Reuben Tam felt the pull of Monhegan, visiting and living there for decades. Tam believed that landscape was not only a subject for representational painting, but also a medium to convey ideas and concerns related to memory, identity, and subjectivity, and he submitted this work (below) in lieu of a diploma portrait. Departing from convention, the Academy’s governing council accepted it, perhaps because it consciously harked back to Bellows’ Three Rollers.

|

|  |  | ||

left: Walter Ufer (1876–1936), Self-Portrait, n.d. Oil on canvas, 30¼ x 25 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; ANA diploma presentation, December 6, 1920 (1271-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. center: Walter Ufer (1876–1936), Jim, 1918. Oil on canvas, 40⅛ x 36¼ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, October 4, 1926 (1272-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. right: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (b. 1940), Snake Dance, 2011. Oil, collage, and mixed media on canvas, 72 x 48 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, November 7, 2012 (2012.79). Photo Credit: Image by Google © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Courtesy Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and American Federation of Arts. | ||||

Jim Mirabel, a member of the Taos Pueblo and Walter Ufer’s friend, domestic employee, and model, is depicted in this expressive portrait. Ufer was a political radical and a passionate Trotskyite who frequently protested the U.S. government’s treatment of American Indians. Upon the artist’s death, Mirabel and another of Ufer’s friends distributed his ashes, in accordance with his wishes, into the winds over the Taos Valley in New Mexico. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana, became the first Native Academician in 2011. Of her diploma work, Snake Dance, she has said, “In a way I was painting a diary of my life.” 2

|

|  | |

| left: Charles White (1918–1979), Mother Courage II, 1974. Oil on canvas, 49¾ x 39⅞ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, March 3, 1975 (1779-P). Photo Credit: Neighboring States © The Charles White Archives. Courtesy American Federation of Arts. right: Charles White (1918–1979), Matriarch, 1967. Oil on canvas, 20 x 17 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; ANA diploma presentation, February 5, 1973 (1765-P). Photo Credit: Image by Google © The Charles White Archives. Courtesy American Federation of Arts. | ||

An academy, by its nature, is an exclusionary organization, and throughout its history, on occasion, the National Academy has been resistant to change in one form or another. That said, as it is a collection built by artists, and not by acquisition committees or museum officials, there are remarkable portents within the Academy’s holdings, years ahead of their time. For example, rather than a likeness of himself, Charles White submitted Matriarch—a portrayal of his great-aunt Hasty Baines, born into slavery in 1857 on the Yellowley plantation in Ridgeland, Mississippi—to the Academy as his diploma portrait. Painted 110 years after her birth, in the thick of a decade rife with political and social unrest, the deeply personal work stood for White as a symbol of wisdom and courage—universal themes also explored in his mature work Mother Courage II. After extensive conservation, Matriarch will be on view for the first time in nearly four decades, and today, as ever, the colloquy between the two paintings is edifying.

|

|  | |

left: William Clutz (b. 1933), Self-Portrait (Walking), 1980. Oil on canvas, 35⅛ x 30¼ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; Gift of the artist, September 23, 2009 (2009.4). Photo Credit : Image by Google © William Clutz. Courtesy American Federation of Arts. right: William Clutz (b. 1933), Autumn Street, 1999. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, May 17, 2006 (2006.11). © William Clutz. Courtesy American Federation of Arts. | ||

Although the world faced by contemporary painters may be infinitely different from the one inhabited by artists of the past, much of the academic training surrounding the human figure has endured. For over half a century, William Clutz has painted figures. Seen in doorways, windows, or street crossings, often faceless, they appear to glimmer and glint as if caught in a quick glance. “When I moved to NYC, it was the people in the street, a stage set with people moving back and forth. I rode my bicycle around so I could catch lighting effects and return the next day, same time, to continue collecting facts and then develop them at home…. People always want to read a face, but, in the street, personalities shine through posture, clothes, hands, a tilt of the head…. You think, ‘I know someone like that.’” 3

|

|  | |

left: Samuel F. B. Morse, Self-Portrait, ca. 1809. Watercolor on ivory, 3¼ x 2⅝ inches. National Academy of Design, New York; Gift of Samuel P. Avery, John G. Brown, Thomas B. Clarke, Lockwood de Forest, Daniel Huntington, James C. Nicoll, and Harry W. Watrous, 1900 (894-P). Courtesy American Federation of Arts. right: Peter Saul (b. 1934), Self-Portrait, 2013. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 55 inches. National Academy of Design, New York; NA diploma presentation, August 7, 2013 (2013.10). © Peter Saul. Courtesy American Federation of Arts. | ||

For America ends with paintings by current academicians whose work addresses contemporary concerns while harking back to the storied history of both this institution and this nation. Although the portrait requirement for academicians was eliminated more than two decades ago, many have continued to pay homage to it. Peter Saul’s diploma work, the only true self-portrait the artist has made up to this point, is a witty and wonderfully gruesome rejoinder to founder Samuel F. B. Morse’s self-portrait, painted when he was not yet twenty years old. Such paintings can provide mirrors for the present, ways of imagining and grappling with the past, and, finally, dreams for a possible future.

|

For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design, organized by the American Federation of Arts and the National Academy of Design, is on view at the New Britain Museum of American Art, Conn., October 16, 2019 to January 26, 2020. The exhibition continues through September 2021 at the Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, Fla.; Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, Tenn.; New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe; Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa; and Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, Calif.; visit www.amfedarts.org/national-academy for dates. The exhibition is curated by Jeremiah William McCarthy, Associate Curator, AFA, and Diana Thompson, Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs, NAD. It is accompanied by a 304-page catalogue, published by the American Federation of Arts and distributed by Yale University Press., which includes essays by Susan Rather, Elizabeth A. Spear, Kenneth Haltman, Akela Reason, Jennifer A. Greenhill, Kimia Shahi, Jonathan Frederick Walz, Alona Cooper Wilson, Alexander Nemerov, Patricia Hills, Jeremiah William McCarthy, and Jarrett Earnest. For more information about the exhibition and accompanying catalogue, call 212.988.7700 or visit www.amfedarts.org.

1. Wendell Stanton Howard, “A Portrait by W. M. Chase,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine 113 (June 1906): 698.

2. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Questionnaire” (2012), National Academy of Design artist file.

3. Conversation with the author, June 2018.

Jeremiah William McCarthy is associate curator at the American Federation of Arts, New York.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2019 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.