Top Museum Acquisitions: 2019 in Review

|

Fig. 1: François-Jules Bourgoin (1786–1821), Family Group in a New York Interior, ca. 1805. Oil on canvas, 30 x 42 inches. Courtesy of Winterthur; Purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle (2019.0006 A). |

|

e live in polarizing times, and the cultural sphere has not been immune. Protests at museums have marked the year, particularly at those with ties to the Sackler family, owners of the Purdue Pharma, makers of Oxycontin. At least seventeen institutions have associations with the Sackler family and Oregon Democratic Senator Jeff Merkley called for the Sackler name to be removed from museums and universities in the United States; Harvard Art Museums, the Jewish Museum of Berlin, the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, and the Tate Museum in London, have announced they were cutting their ties. Frick Collection supporters Bernard and Lisa Selz were “outed” for their $3 million-plus support to organizations that promote anti-vaccination campaigns. At MoMA, the activist feminists The Guerilla Girls staged protests against board of trustee members with ties to convicted sex-offender Jeffrey Epstein. And demonstrators occupied the Brooklyn Museum to demand a more racially and ethnically diverse staff in the wake of the hiring of a white curator of the institution’s African art collection. Life at the major art museums abroad this year has been no less fraught, with demonstrations at the Louvre in Paris, the British Museum and Tate Modern, and the National Gallery protesting sponsorship by oil companies.

The Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library in Delaware acquired two paintings, Family Group in a New York Interior (Fig. 1) by François-Jules Bourgoin (active 1796–1812), and Self-Portrait of John Lewis Krimmel with Susannah Krimmel and her Children by the Philadelphia artist John Lewis Krimmel (1786–1821), whose principal value may be on the light they shed on life in the still new United States of America.

|  | |

Left Fig. 2: Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933), Side Chair, ca. 1891-93. Primavera and American ash, varicolored wood and metal micro-mosaic marquetry, glass balls in brass claw feet. 35¼ x 18¼ x 18½ in. Courtesy, Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right Fig. 3: A Pair of German Parcel-Gilt Silver Torah Finials, Jurgen Richels, Hamburg circa 1688-89. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Purchase with funds by the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation and Jetskalina H. Phillips Fund. | ||

The Morgan Library & Museum took possession of a collection of eighteenth-century manuscripts and books bequeathed by Jayne Wrightsman in honor of her friend and longtime Morgan board member, Mrs. Annette de la Renta. Among the illustrated books are the two editions of La Fontaine, the four-volume folio with plates after Jean-Baptiste Oudry, and the Fermiers Généraux two-volume octavo with plates after Charles Eisen, both bound in gilt-tooled dentelle morocco. Also included are books on politics, religion, court entertainments, music, and military strategy.

The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, added to its decorative arts collection with a circa 1891–93 side chair by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), better known for his stained glass Art Nouveau pieces. The side chair (Fig. 2), purchased from a dealer, is ornamented with intricate mosaic, marquetry, floral carvings, and tapered legs that terminate in small glass balls. While this chair’s form is based on traditional early nineteenth-century British furniture designs, its ornament takes inspiration from East Indian woodwork that was a popular import at the time. The Tiffany chair strengthens the links between the Huntington’s American decorative arts display and the works on view in the Huntington Art Gallery, where objects from the British Aesthetic Movement are highlighted.

|  | |

Left Fig. 4: Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment, 1833–34. Oil on canvas, 18⅛ x 153⁄16 in. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Purchase funded by the Brown Foundation Accessions Endowment Fund. Right Fig. 5: Salvador Dalí (Spanish 1904-1989), Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936 (cast 1971). White paint on bronze, 15 x 3⅛ x 3⅞ in. Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas. Gift of Daniel Malingue (MM.2019.3). Photo by Kevin Todora. © 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society. | ||

|  | |

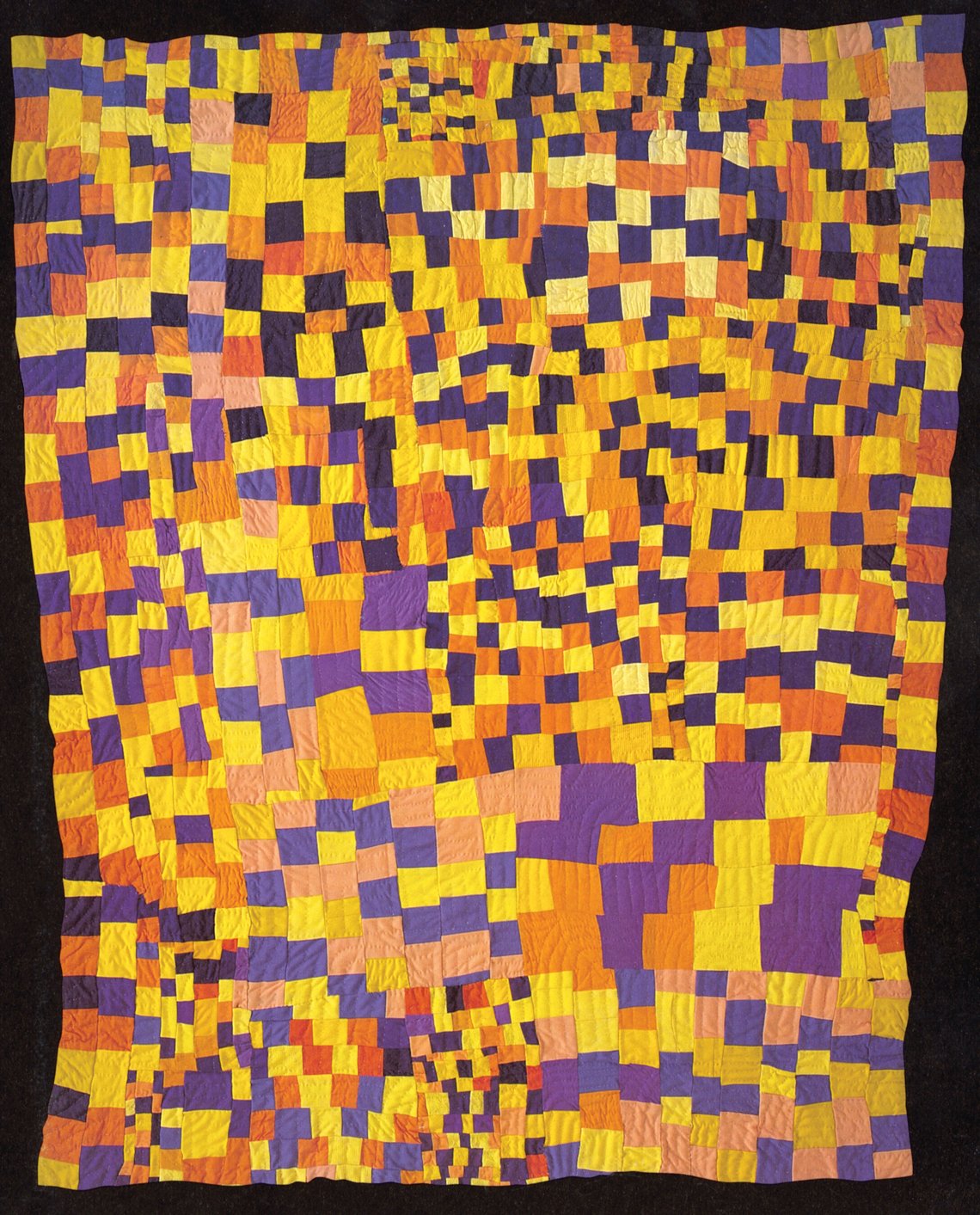

Left Fig. 6: Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641), Queen Henrietta Maria, 1636. Oil on canvas. 41⅝ × 33¼ in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Bequest of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman in honor of Annette de la Renta, 2019 (2019.141.10). Right Fig. 7: Rosie Lee Tompkins, Three Sixes, 1986; quilted by Willia Ette Graham. Polyester, polyester double knit wool jersey, and cotton muslin backing; 97 x 81 in.; Bequest of the Eli Leon Living Trust, University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Photo: Sharon Risedorph. © Estate of Effie Mae Howard. | ||

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, may be principally known for its Egyptian artifacts and its decorative arts and paintings by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American artists, but the museum has been expanding its reach into other areas, such as contemporary art and objects by African-American artists. It also has sought to increase its holdings of Judaica, acquiring from a Sotheby’s auction two silver parcel-gilt Torah finials: a pair from Hamburg, Germany (ca. 1688–89) (Fig. 3), and a pair by British silversmith Edward Aldridge dating from 1764. The English pair, purchased for $187,500, was sold to benefit the Central Synagogue, London.

In May, the J. Paul Getty Museum purchased a group of seventeen ancient engraved gems from the collection of Roman art dealer Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1965). (The Getty has made it clear that the great majority of the Sangiorgi gems were acquired before World War II and were in no way Holocaust loot.) The group acquired by the Getty includes Greek gems of the Minoan, Archaic and Classical periods, as well as Etruscan and Roman gems, some of which are in their original gold rings. According to Timothy Potts, director of the museum, the acquisition “brings into the Getty’s collection some of the greatest and most famous of all classical gems, most notably the portraits of Antinous and Demosthenes.” The gem portraying Antinous, the young lover of the Emperor Hadrian (ruled 117–138 AD), was engraved on an unusually large black chalcedony stone. A frontal portrait of Demosthenes, the 4th century BC Greek orator, is signed by the gem engraver Dioskourides, the court gem engraver to the Emperor Augustus (ruled 27 BC–AD 14), regarded as one of the greatest gem engravers of Roman times.

|

Fig. 8: Elizabeth Catlett (Mexico, 1915–2012), Seated Woman, 1962. Carved wood. 22½ x 13½ x 7 inches. Saint Louis Art Museum, Friends Fund Endowment; Gift of Edward J. Costigan in memory of his wife, Sara Guth Costigan, by exchange; the James D. Burke Art Acquisition Fund, the Eliza McMillan Trust, Funds given by the Alturas Foundation, and Museum Purchase (75:2019). © 2019 Catlett Mora Family Trust / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Image courtesy of Swann Auction Galleries. |

In the past year, the Getty also purchased a rare and well preserved painting, Virgin and Child with Saint Elizabeth and Saint John the Baptist, by Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572), and a pair of rare marble sculptures, The Annunciation (about 1333–34), by Giovanni di Balduccio (ca. 1290–1339). The museum also bought Corpus Christi (ca. 1490–1500), a small-scale wooden sculpture depicting the crucified body of Christ by Veit Stoss.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which owns several small-scale paintings by French painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), purchased another from a Parisian gallery, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1833–34), for an undisclosed price (Fig. 4). The painting is the first version of the artist’s famed composition Femmes d’Alger (1834), now in the collection of the Louvre in Paris, and a highlight of the historic Delacroix retrospective co-organized by the Louvre and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018.

The Meadows Museum of Southern Methodist University in Texas is renowned for its collection of Spanish art, starting with the original 1961 gift of scores of paintings by Goya, El Greco, and other Iberian artists, from Texas oilman Algur Meadows (1899–1978). In the almost sixty years since that original gift, the Meadows Museum has been adding diligently to its collection, and in 2019 added four new works—some old and some newer, not all paintings. They include Manuel Ramírez de Arellano’s terra cotta sculpture Our Lady of Solitude (1769); Salvador Dali’s bronze sculpture Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936, cast 1971) (Fig. 5); a drawing by Ignacio Zuloaga, Portrait of Margaret Kahn (1923); and the painting Orchard in Seville (ca. 1880), by Emilio Sánchez Perrier.

|

Fig. 9: Tarsila do Amaral (Brazilian, 1886–1973), The Moon (A Lua), 1928. Oil on canvas, 43⅓ x 43⅓ in. Courtesy, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase. |

| |

Fig. 10: Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Running Freed More Slaves Than Lincoln Ever Did, 1995. The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchase with exchange funds from the Pearlstone Family Fund and partial gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art (2019.27). © Mary Lovelace O’Neal. |

One of the biggest winners in the Old Masters realm was The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which received a bequest of 375 artworks and $80 million from the late Jayne Wrightsman, who died in April at the age of 99. The bequest includes gifts to The Met’s departments of drawings and prints, European paintings and sculpture, decorative arts, as well as to the departments of Asian art and Islamic art and the Watson Library. Among the key donations were Van Dyck’s portrait of Queen Henrietta Maria (Fig. 6) and Delacroix’s Rebecca and the Wounded Ivanhoe, as well as six canvases by Canaletto. The $80 million was added to the existing Wrightsman Fund, which supports acquisitions of works of art from Western Europe and Great Britain created between 1500 and 1850.

Among other Old Master highlights in museum collecting during the past year was the National Gallery of Art’s acquisition of a 1529 painting Venus and Cupid by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) and a circa 1560 painting by Florentine artist Maso da San Friano (1531–1571), Holy Family with the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, which entered the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Artworks and other cultural objects by women artists, African-American artist, Latino artists, and artists from other continents, specifically, South America, Africa, and Asia have been the focus of many museums. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art sold an untitled 1960 Mark Rothko painting from its collection for $50 million, and used the money to purchase artworks by Rebecca Belmore, Forrest Bess, Frank Bowling, Leonora Carrington, Lygia Clark, Norman Lewis, Barry McGee, Kay Sage, Alma Thomas, and Mickalene Thomas. Among these pieces is Mickalene Thomas’s 2011 painted portrait of a transgender woman named Qusuquzah, Qusuquzah, Une Très Belle Négresse 1, Frank Bowling’s large-scale 2018 painting Elder Sun Benjamin, and Rebecca Belmore’s large-scale 2018 ceramic sculpture Tarpaulin No. 1.

The Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington purchased a series of prints by conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas, an 1871 oil painting by Robert Duncanson, and a 1940 poster by Robert Pious. The Thomas work, Black Survival Guide, or How to Live Through a Police Riot (2018), was commissioned by the museum. In total, 74 percent of the museum’s acquisition funds spent in 2018 went toward acquiring works by women artists and artists of color.

|

Fig. 11: Anne Vallayer-Coster, Still Life with Mackerel, 1787. Oil on canvas, 19½ x 24 in. Kimbell Art Museum; Gift of Sid R. Bass in honor of Kay and Ben Fortson. |

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens purchased a series of thirty-two etchings with aquatint (2005–14) by four artists who are part of the Gee’s Bend group of quilters. Also acquired was a 1969 collage, Blue Monday by Romare Bearden (1911–88). Collector and scholar Eli Leon bequeathed his collection of nearly three thousand works by African-American quiltmakers to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive at the University of California (Fig. 7). The gift, which includes more than five hundred works by Rosie Lee Tompkins, an artist who helped raise the profile of quilting in the art world, marks one of the largest gifts of African American art ever donated to a museum.

-c.jpg) | |

Fig. 12: Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room—My Heart is Dancing into the Universe, 2018. Wood and glass mirrored room with paper lanterns. 119⅝ x 245⅛ x 245⅛ in. Courtesy Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / Singapore / Shanghai and Victoria Miro, London / Venice. © Yayoi Kusama. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. |

Constance E. Clayton, a board member of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where she founded the African American Collections Committee in 2000, donated seventy-eight works by African-American artists to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. The collection spans from the late nineteenth century to the late twentieth century, and includes pieces by Charles White, Sam Gilliam, and Romare Bearden, among others.

The Saint Louis Art Museum set a new record for the artist Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012) when they purchased at Swann Auction Galleries (for $389,000) her carved mahogany sculpture Seated Woman (1955–59) (Fig. 8). Catlett, the granddaughter of former slaves, used her art to advocate for social change against racism and for feminism, and worked in both the states and in her adopted Mexico. The Museum of Modern Art, acquired Tarsila do Amaral’s (Brazilian, 1886–1973) The Moon (A Lua), painted in 1928 (Fig. 9). Tarsila do Amaral is a foundational figure for modern art in Brazil, and a central protagonist in the transatlantic cultural exchanges that informed it. Her paintings from the 1920s ignited a radically new iconography of enduring influence in her native country. This is the artist’s first work to enter MoMA’s collection.

Also helping to rewrite the standard story of American art, the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum in Georgia, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Alabama, and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. all acquired pieces from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation’s collection, which focuses on black artists working in the American South. The Whitney Museum of American Art purchased Norman Lewis’ 1960 painting American Totem, and the Broad in Los Angeles purchased David Hammons‘s African-American Flag (1990)the first piece by the artist to enter the museum’s collection and is part of a series of five editions.

| |

Fig. 13: Artist unidentified, Memorial: Gate of Heaven, possibly Maine, ca. 1850. Paint on wood, 12⅝ x 29½ x 3⅜ in. Collection of American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Jacqueline Loewe Fowler (2019.9.3). | |

| |

Fig. 14: Artist unidentified, Barbershop Stand and Shelf, ca. 1940-1950. Courtesy, High Museum. | |

Kehinde Wiley (b. 1977) gained nationwide attention for his 2018 portrait of former President Barack Obama that was commissioned for the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. His artworks, which regularly borrow from Old Master subjects and styles but substitute more contemporary figures into these images, have become must-haves for museums. The Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas, bought his 2018 Portrait of a Florentine Nobleman, which is based on a sixteenth-century painting by Francesco Salviati, while the Oklahoma City Museum of Art purchased his 2018 Jacob de Graeff (with funds from the Carolyn A. Hill Collections Endowment and the Pauline Morrison Ledbetter Collections Endowment), which is modeled on seventeenth-century Dutch artist Gerard ter Borch’s portrait of Jacob de Graeff. The Saint Louis Art Museum purchased the artist’s 2018 Charles I, which is based on a 1633 portrait of the English king by Daniel Martensz Mytens the Elder.

No less interested in expanding its holdings in the work of women, African-American and artists from around the globe is the Baltimore Museum of Art. Last year the museum sold off from its permanent collection a number of works by major modern artists, including a Rauschenberg and a Warhol, in order to raise money to acquire works by women artists and artists of color. Among the artworks purchased from the proceeds of recent deaccessioned works is a drawing by David Driskell, a mixed media piece by Faith Ringgold, and a 1995 oil on canvas work by Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Running Freed More Slaves Than Lincoln Ever Did (Fig. 10)—all African-American artists—in addition to pieces by Jamaican-born mixed-media artist Ebony G. Patterson (...we lost...for those who bear/bare witness, 2018), Cuban-born multimedia artist Ana Mendieta (Blood Inside Outside, 1975), and Rumanian artist Geta Brătescu (Mother Courage, 1966).

The works of women artists have also been on the wish list of various museums, such as the Monterey Museum of Art, which acquired two pieces by feminist artist Judy Chicago, the 1962–64 acrylic on stoneware, In My Mother’s House, and the 1962–64 acrylic on Masonite, Emblem. Both pieces explore female empowerment. Looking back a bit in time, the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, was gifted a 1787 painting Still Life with Mackerel by Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744–1818) (Fig. 11). Both the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston and Crystal Bridges Museum in Arkansas acquired works by Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama (Fig. 12). who, like Kehinde Wiley, has recently jumped to the top of every museum director’s bucket list. Kusama has created twenty or so installations, called “Infinity Rooms.” The ICA’s room is called Love is Calling (2013), while the Crystal Bridge’s is My Heart is Dancing Into the Universe (2018).

|

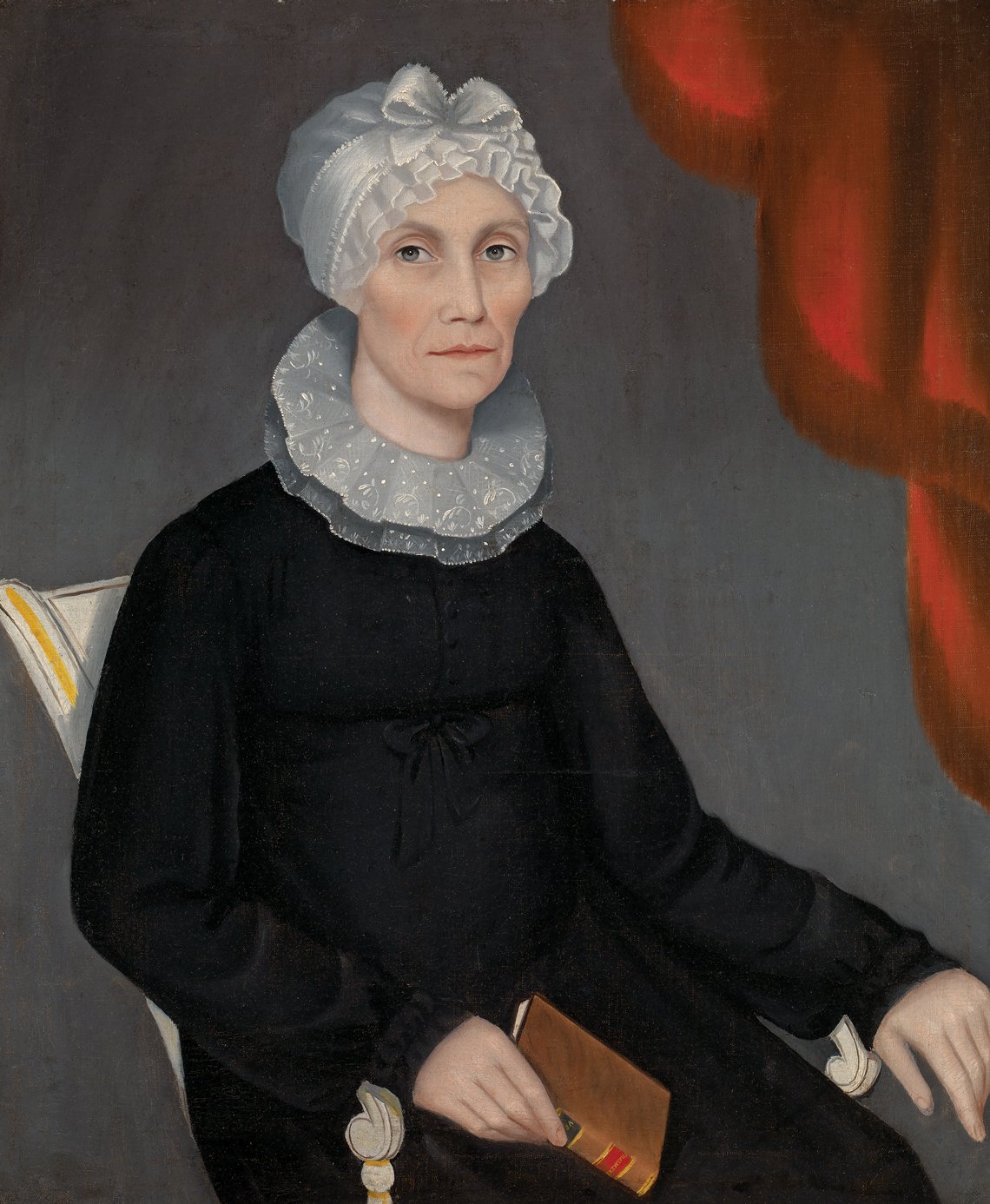

Fig. 15: Ammi Phillips, Portrait of Mrs. Robinson, ca. 1819. Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of Ralph and Bobbi Terkowitz (2019.6.11). |

American folk art remains a focus of many museums, primary among them the American Folk Art Museum in New York. AFAM acquired an unusual carved memorial that employs motifs more commonly seen in 19th-century needlework or painted mourning pictures (Fig. 13). The elements of landscape and architectural detail show the influence of the rural cemetery movement, which, in keeping with the era’s culture of sentimentality, promoted bucolic, romantic surroundings for sites of mourning. Using crowd sourcing to decide which of four objects on view at their 2019 Collectors Evening would enter the High Museum of Art’s collection, the votes were cast resulting in the acquisition of “Barbershop Stand and Shelf” by an unidentified artist (Fig. 14). Rounding out this category, collectors Ralph and Bobbi Terkowitz, who sold their collection at Sotheby’s in January 2018, donated to the Smithsonian American Art Museum a portrait of a Mrs. Robinson, circa 1819, by artist Ammi Phillips (Fig. 15).

Daniel Grant is a freelance writer specializing in the arts industry.

|

This article was originally published in the 20th Anniversary (Spring/Summer 2020) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.