American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection

America is a nation of stories. Everyone has a story to tell—a life lived as a witness to and participant in events both private and shared. The stories that we tell as individuals are single strands in a grander narrative. American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection captures the power of storytelling through artworks from the American Folk Art Museum collection. In this era of unremitting uniformity and conventionalizing through mass means of commercialization, communication, technology, and media, it is the very diversity of experience, heritage, perspective, and place that revitalizes, renews, strengthens, and unites a nation. The artworks in the exhibition are organized into four sections—Founders, Travelers, Philosophers, and Seekers—that offer reflections on such themes as nationhood, freedom, community, imagination, opportunity, and legacy. Visual juxtapositions and contextual information reveal the vital role that folk art plays as a witness to history and a reflection of the world at large through the eyes, heart, and mind of the artist. The artworks remind us that many of the issues of today—anti-immigration, political turmoil, economic uncertainty, and loss of personal liberties—were present in the past. They remind us that there is loneliness and heartbreak, but also family and love. They hold in common the truths that act as the ballast against which we judge our actions. Capturing the tumult of a developing American identity filled with contradictions and reflecting the challenges and disparities of a polyglot society, the work of these artists lends coherence to our own experience. In this, the art functions as testifier to and revision of the choices that we, and others, have made. It grants the power to transcend.

|

|

Christian Strenge (1757–1828), Liebesbrief, East Petersburg, Penn., ca. 1790. Watercolor and ink on cut paper. Diam. 13¼ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Ralph Esmerian (2005.8.37). Photo by Schecter Lee. |

In 1776, Hessian-born Johann Christian Strenge was one of twelve hundred men who either were conscripted or enlisted in the 5th company of the Grenadier Regiment, led by Colonel Johann Gottlieb von Rall, to fight for the British during the American Revolution. The troops arrived in New York in August; by December, the majority had been taken captive in the pivotal Battle at Trenton, when General George Washington’s Continental Army crossed the Delaware River to make a surprise attack in the early morning hours of December 26. The Hessian soldiers were marched to Philadelphia where they were paraded through the streets before being interned in camps in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Strenge gained his freedom in 1777, and rejoined his regiment. After the war, he remained in Lancaster, married, and had a daughter. Two years after the untimely deaths of both wife and child, he remarried and, by 1794, had purchased land in East Petersburg, where he became a respected schoolteacher, scrivener, justice of the peace, and property owner. A member of the Reformed Church, he made many forms of fraktur for Mennonite, Lutheran, and Reformed constituencies. These included elaborate papercut Liebesbriefe, or love letters, such as this example.

|

|

Ruth Whittier Shute (1803–1882) and Dr. Samuel Addison Shute (1803–1836), Eliza Gordon, Peterborough, N.H., ca. 1833. Watercolor and gouache on paper with applied gold paper, 24⅝ x 19 inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Museum purchase (1981.12.24). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

Eliza Gordon (1813–1893) was around twenty years of age when she gazed clear-eyed and open-faced from her watercolor portrait that was painted by Dr. Samuel Addison and Ruth Whittier Shute. Like so many young women living on rural New England farms, Eliza left home in Henniker, New Hampshire, and found employment in the Phoenix Factory in Peterborough, where she worked in the preparation room. This was one of many textile mills that were bringing prosperity to the river towns of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Young women were lured by the promise of opportunities for self-sufficiency and broadened horizons. The reality of mill life and work was much harsher, as they came to appreciate and ultimately rebel against, staging the first labor strike in the United States in 1824, and organizing the first union of women workers a decade later. Their faces would have remained largely unknown but for the work of the Shutes, whose distinctive portraits in watercolor on large paper offered a less expensive though no less impressive alternative to oil on canvas.

The couple formed an unusual artistic collaboration shortly after they were married in 1827. Their respective roles in this partnership are indicated on a small number of portraits inscribed: “Drawn by R.W. Shute/and/Painted by S.A. Shute.” The Shutes employed a number of unorthodox techniques and materials in their work. Oils were interspersed with layers of varnish and glazes; watercolors were supplemented with pastel, gouache, pencil, metallic paint, foil, collage, and gum arabic; areas of paper were even left blank to suggest transparency and other effects. Most of the watercolors feature vigorous diagonal or horizontal strokes in the background. After Dr. Shute’s death at the age of thirty-three, Ruth continued to paint in oil and pastel, remarrying in 1840 and moving to Kentucky.

|

|

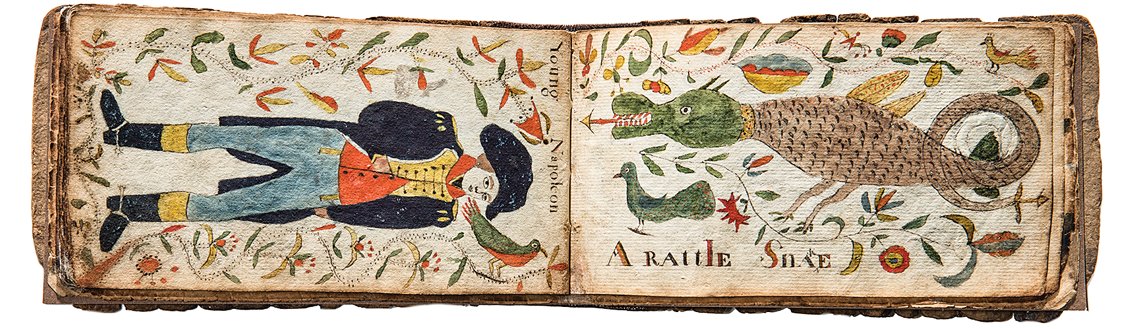

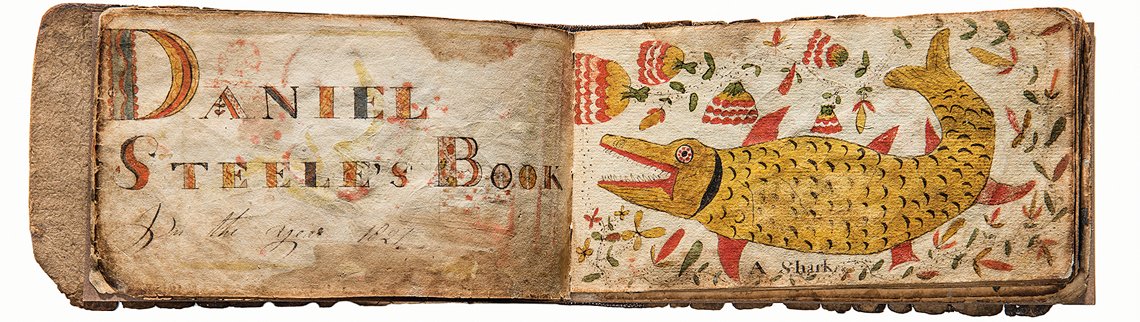

Tunebook, Daniel Steele (n.d.) Eastern United States,1821. Watercolor and ink on paper, 5 x 8½ inches (closed). Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Museum purchase with partial funds provided by Becky and Bob Alexander, Lucy and Mike Danziger, Jane and Gerald Katcher, Donna and Marvin Schwartz, Kristy and Steve Scott, and an anonymous donor (2014.1.1). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

|

Presbyterian immigrants of Scotch-Irish descent, fleeing unrest and displacement in Ulster, began arriving in the American colonies beginning in the seventeenth century and continuing into the early nineteenth. Settling initially in Pennsylvania, New York, and New England, many continued their journey further into frontier areas of Virginia, North Carolina, and Ohio, where there were greater opportunities. Daniel Steele, whose name is inscribed in this remarkable illustrated and illuminated tunebook, is not identified, but was of Scotch-Irish heritage based on the psalm tunes contained in these pages. They comprise ten of the twelve traditional tunes used with the Scottish Psalter published in 1650, the metrical version of the psalms in which singing constituted a primary feature of the denomination. It has recently been recognized that a small number of such illuminated psalm books, once believed to be of Pennsylvania German origin, were actually made by members of Scotch-Irish communities. They are written in English, and the earliest examples include the sanctioned tunes that are written using Sol-Fa notation, a system of musical notes that enabled all congregants to sing the sacred psalms. This booklet of forty some-odd pages further includes several drawings that apparently derive from English and Irish sources, such as a depiction of Springhill Castle in Ireland. A page of particular note shows a figure in the guise of a plague doctor, wearing the characteristic mask in the form of a beaked bird and carrying a scythe, a symbol of death. The imagery may be connected to two pages whose inscriptions indicate the death of an infant.

|

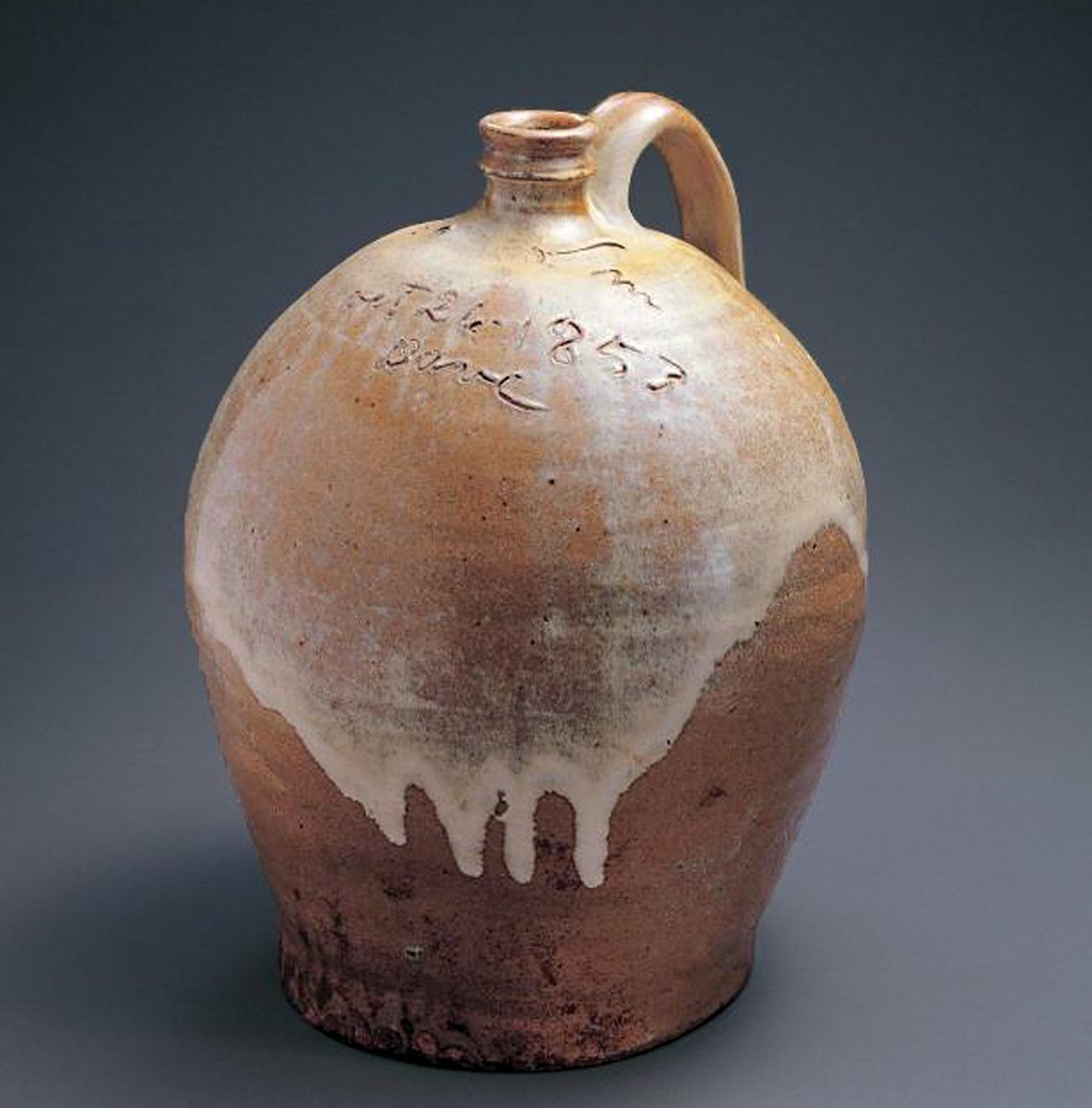

“Dave belongs to Mr. Miles / Wher the oven bakes & the pot biles / July 31, 1840 / – Dave”

“I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all—and every nation. / August 16, 1857 / – Dave”

|

Jug, David Drake (ca. 1800–ca. 1870), Lewis J. Miles, Stony Bluff Plantation Pottery, Edgefield County, S.C., 1853. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 14½, D. 12, W. 11½ in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Sally and Paul Hawkins, (1999.18.1). Photo by John Parnell. |

How do we fathom the temerity of an enslaved potter incising a name, poem, or date, indelibly fired into the clay body of a stoneware vessel? The history of the turner who signed his vessels as “Dave” has been partially recovered, in large part through his own self-actualization expressed in snippets of original poetry and observations embedded into utilitarian pots intended simply to store food and drink. More than one hundred examples, fashioned largely between 1834 and 1864, further bear his name or date. In the Federal Census of 1870, the potter listed his name as “David Drake, occupation turner,” and that is how this discussion will refer to him.

Drake was born into slavery around 1800. Until 1833, he belonged to the household of Harvey Drake, who, with his uncle and partner, Abner Landrum, operated a pottery just outside Edgefield, South Carolina. At a time when it was not lawful to teach enslaved people to read and write, Drake’s unusual literacy may have been a result of his employment at the local newspaper, the Edgefield Hive, published by Landrum. David Drake grew to be one of seventy-six enslaved African Americans known to have worked in Edgefield’s potteries, and one of only two identified potters capable of building enormous vessels of more than twenty-gallon capacity.

The earliest piece attributed to his hand is dated 1821. In the ensuing years, he worked for and was traded among potteries in the Edgefield district known as Pottersville, whose owners—Drake, Gibbs, Landrum, Miles, and Rhodes—were interrelated by partnerships and through marriage. Between 1840 and 1843, and again after 1849, David Drake became the property of Lewis J. Miles, who seems to have supported his textual expressions and whose name appears on this ovoid jug. By contrast, the pots are resoundingly mute during the years 1843 to 1848, when he was working for Franklin Landrum. After emancipation, Dave took the surname of his first owner, Drake.

In 1859, the Edgefield Advertiser published a remembrance of the Edgefield potteries: “The first sight of that furnace nearly thirty years ago—can we ever forget it? … Do we still mind how the boys and girls used to think it a fine Saturday frolic to walk to old Pottersville and survey its manufacturing peculiarities? To watch old Dave as the clay assumed beneath his magic touch the desired shape of jug, or jar, or crock, or pitcher, as the case may be?”

|

|

Crazy Quilt, Clara Leon (1845–1921), Las Vegas, N. Mex., ca. 1885. Silks and velvets with silk and chenille embroidery and paint, 71½ x 66 inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of the family of Robert A. Coplin (2016.20.1). Photo by Adam Reich. |

This quilt is believed to have been made by Clara (Dobriner) Leon. Clara was born in Hoffenheim or Heidelberg, Germany. She came to the United States on March 11, 1867, arriving in the port of New York on the ship America. The following year, she married German-born Pincus (Peter) Leon (circa 1831–1896) in Manhattan. Following the migration pattern of many immigrant German Jews, the Leons joined a growing Jewish pioneer community on the western frontiers as they traveled by covered wagon seeking greater economic opportunities. In 1869, they were living in Independence, Missouri, where their daughter, Carrie, was born. By 1873, they were in Las Vegas, New Mexico, where the infamous Doc Holliday once hung his shingle. As a merchant, Pincus was attracted to the location by the proximity to the Santa Fe Trail and expansion of commerce through the developing railway system. In 1884, the Leons were among thirty-six Jewish families living in Las Vegas who established Temple Montefiore, the first congregation in the New Mexico territories. They also contributed to the Las Vegas Academy, which their daughter attended.

Clara came from a cultured and musical family. Family lore states that her piano also traveled by covered wagon. This may account for some of the musical motifs in the fashionable and elegant textile that features sumptuous velvets, chenille threads, and silk embroidery, perhaps available through her husband’s business or the three-story department store founded by Charles Ilfeld, another Jewish pioneer. Each of the borders displays a bounty of floral and leaf arrangements suggestive of the changing seasons from fall leaves to winter sprays. One block includes the Odd Fellows’ interlocking three rings. By 1892, Clara and Pincus were living in Trinidad, Colorado, and were members of Temple Aaron, the oldest synagogue in Colorado, which was founded in 1883. She was a charter member of the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society, and participated in fundraising fairs and teas. Clara and Pincus Leon are buried next to each other in the Masonic (also Odd Fellows) Cemetery in Trinidad Colorado, in a section devoted to members of the congregation.

|

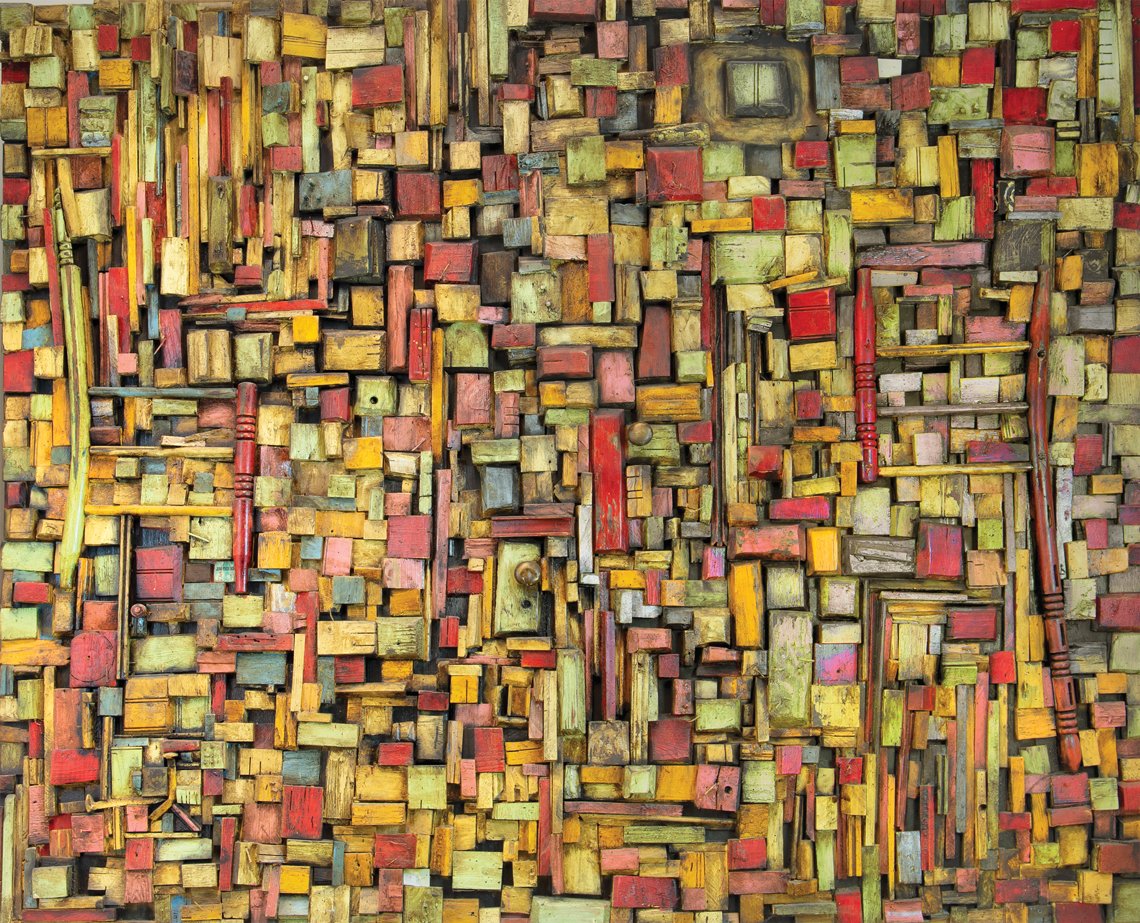

“When I first purchased my house in Treme, there were still a few pieces of furniture left over from the last owner. It was for decades, a rooming house that housed many of New Orleans single male musicians, and was owned and operated by a woman known to the neighborhood as Mother Sister. After Katrina, one of the chairs she left behind was damaged along with the rest of the house, so I cut up the chair and put it in this piece.” —Jean-Marcel St. Jacques

|

Jean-Marcel St. Jacques (b. 1972), Mother Sister May Have Sat in That Chair When She Lived in This House Before Me, New Orleans, La., 2014. Reclaimed wood, nails, and antique hardware on plywood, 84 x 96 inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, LLC (2014.18.2). |

Jean-Marcel St. Jacques is a twelfth-generation Afro-Creole. He was raised in Richmond, California, a small city in the Bay area settled by many black families like his own who had fled Louisiana and Texas between the 1940s and 70s to escape racial oppression. He returned to Louisiana sixteen years ago, inspired to reconnect with the land of his ancestors. In the wake of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina, St. Jacques began to make art with wood salvaged from his damaged home in the Treme neighborhood of New Orleans, and also to “mask” as a medicine man in the Black Masking Indian tradition.

Many of his pieces take the form of “wooden quilts,” patchwork constructions of strips of wood reclaiming and transforming the stories of those lives touched by Katrina. Constructed from the detritus of his home, the fragments of wood are studded with nails, hinges, doorknobs and other evidence of function. Two self-portraits embedded into the construction imbue the work with folk magic and the spirit of his ancestors. Initially St. Jacques colored the wood fragments with house paints that were leftover from renovating his home. He does not like to reveal too much of his process saying, “Like any good Creole cook, the secret is in the roux, and I ain’t telling y’all what that is.”

According to the artist:

My great-grandmother made patchwork quilts.

My great-grandfather was a hoodoo man who collected junk and re-sold it for a living.

As a visual artist, I work mainly with wood and junk.

As the great-grandson of hoodoos, I work folk magic.

These wooden quilts are my way of being with the spirits of my late great elders.

They are also my way of finding a higher purpose for the pile of debris hurricane Katrina left me with. [They] grew out of an impulse to find beauty in the ugliness of one of the worst human disasters this country has ever experienced, and, on a more practical note, to save and rehab my house for me and my family.

|

|

Screen for the Order of United American Mechanics, Clark V. Eastlack Jr. (1836–1871), Philadelphia, Penn., 1860–1871. Oil on canvas, 47 x 49 inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Charles, Barbara and Chip Reinhard (2011.1.1). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

Throughout its history, the United States has experienced periods of intolerance—sometimes violent—toward newcomers, usually instigated by fear and resentment during times of economic depression and war. The Order of United American Mechanics (OUAM) was an anti-Catholic and Nativist secret society that was organized in Philadelphia in 1845, anticipating the rise of the American Know Nothing Party. It was born as a growing number of Catholic Irish, Italian, French, and German immigrants were entering the city in increasing numbers through the port of Philadelphia. The new arrivals were viewed as direct threats to the scarcity of labor opportunities available to native-born Americans. The organization was founded on principles of promoting “American-labor” and the purchase of goods and services from only native-born Americans. In its structure, it was modeled after the Freemasons; its logo of an arm and hammer held in a fist within a square and compass was a play on the Masonic device.

The OUAM soon developed a body of rituals for its members, loosely based on older fraternal organizations. Teaching charts were an accepted part of the paraphernalia, providing a visual means of transmitting the society’s beliefs, symbols, and rituals to new members and reinforcing the same for its established members. This is one a of series of such screens or charts illustrating American workers and painted in Philadelphia by Clark Vernal Eastlack Jr., an ornamental painter on North 2nd Street. Eastlack was a second-generation painter and a member of the OUAM. His death in 1871 at age thirty-six may have been sudden, as he is still listed in the city directory for that year. Eastlack’s older brother Francis composed “The Great Know-Nothing Song, I Don’t Know,” which was published at the height of Know Nothing influence and distributed at Philadelphia bookstores.

|

|

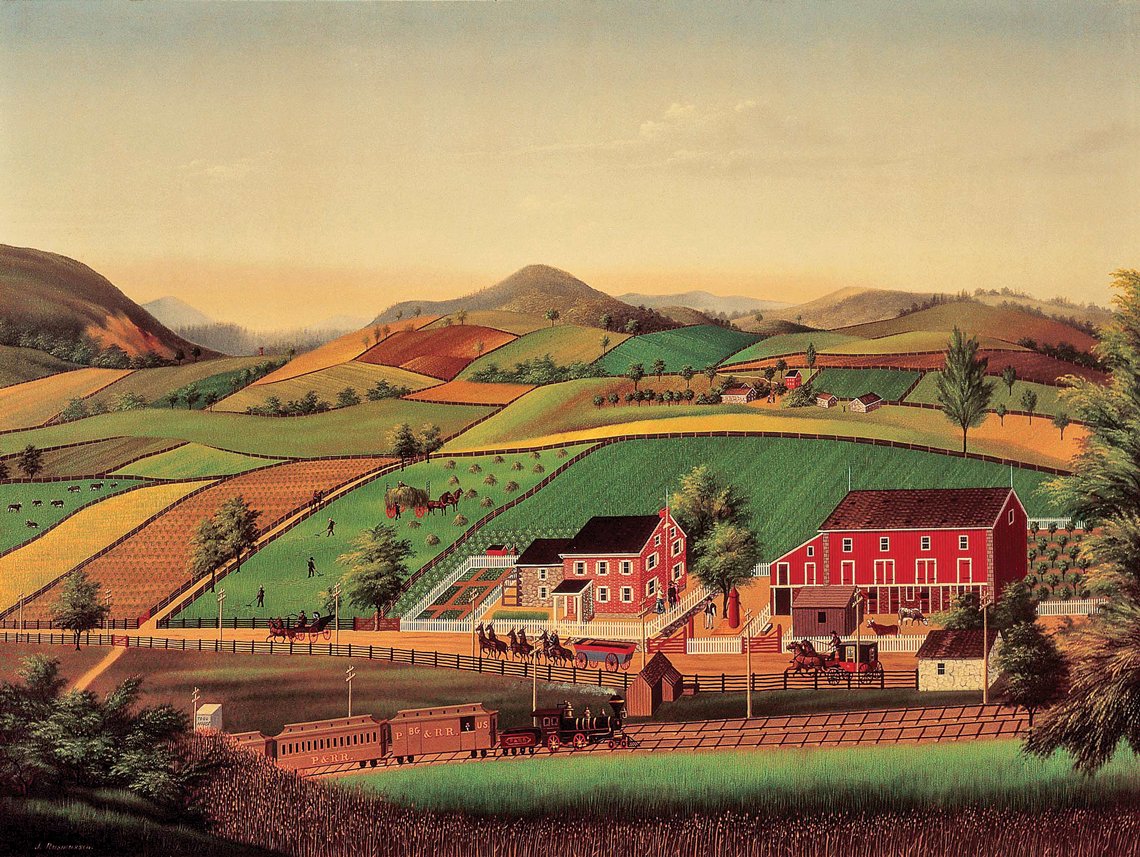

John Rasmussen (1828–1895), John Van Reed Evans Homestead and Farmscape, Berks County, Penn., ca. 1879–1886. Oil on zinc-plated tin, 26⅜ x 35⅜ inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Ralph Esmerian (2005.8.15). Photo ©2000 John Bigelow Taylor. |

The idyllic world portrayed in this scene presents a snapshot of Berks County in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. In the foreground, a hub of neat and impressive homes is brought to busy life by people, coaches, and wagons traveling along the road. A locomotive and cars chug into view from the opposite direction, running along the tracks of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad (P&RR), one of the first in the United States and originally constructed to haul coal from Pennsylvania’s coal region to Philadelphia. Telegraph poles installed at regular intervals along the road and the tracks signify the use of this new technology to direct traffic along the extensive routes and to dispatch trains. Behind this modern nexus are enacted the traditional seasonal activities of a prosperous working farm, the beautiful patchwork of fields and crops separated by slim wood fences. In the far distance are smoky, blue mountains and misty forests. John Rasmussen, the artist, was living in very different circumstances when he painted this optimistic scene. He had emigrated to the United States from his native Germany in 1865. By 1867, he was working as a painter and housepainter in Reading, Pennsylvania. On June 5, 1879, widowed, crippled with rheumatism, and debilitated by chronic alcohol abuse, Rasmussen was committed to the Berks County Almshouse. In his remarkably fresh vistas of the almshouse and surrounding properties painted in oil on zinc panels reclaimed from the wagon and machine shops, Rasmussen closely followed the prototype innovated by Charles C. Hoffmann (1820–1882), a fellow German immigrant, with whom he overlapped for a period of three years until Hoffmann’s death. The elder Hoffmann appears to have trained as a lithographer, and often includes a cartouche and a legend in his works that are painted in a flat, stylized manner. Most, if not all of Rasmussen’s detailed renderings of the Almshouse facilities and grounds were painted for directors and those closely associated with the Almshouse. Other works were special commissions depicting nearby private properties. This scene has now been identified as the homestead in Spring Township belonging to John Van Reed Evans (1804–1864), a prosperous farmer of Welsh descent whose lineage is intermingled with Berks County’s most prominent families, including the Van Reeds, whose own farm was rendered by Hoffmann in 1872.

My thanks to Lisa Adams, Vicky Heffner, Michelle Lynch, George M. Meiser, Sharon Merolli, Richard Polityka, and Susan Speros for their assistance in identifying this scene.

|

|

Judith Scott (1943–2005), Untitled, Oakland, Calif., 1988–1989. Yarn and twine with unknown armature. H. 8, D. 36, W. 25 in. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Creative Growth Art Center, Oakland, California (2002.21.2). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

One night, in Columbus, Ohio, inseparable seven-year-old twins Joyce and Judith Scott fell asleep “curled together, like soft spoons” in the bed that they shared. In the morning, Judith was inexplicably gone and Joyce was alone. In 1950, there were few options available to families who had children with developmental disabilities. It would be decades before federal legislation was enacted to protect members of society with physical and developmental challenges. Vulnerable children like Judith Scott, born with Down syndrome, were virtually discarded. When Judith was assessed for her potential to be educated, neither her family nor the assessor recognized that she was profoundly deaf. Her lack of verbal response and engagement were taken as further signs of her inability to be mainstreamed to any appreciable extent. In mid-century, this meant that she was sent to a state institution where the conditions were deplorable. Remarkably, Scott survived in this environment for thirty-five years before her now-adult sister was able to wrest legal guardianship in 1985. Joyce enrolled Judith in the Creative Growth Arts Center in Oakland, California, founded to encourage creative expression among those who were intellectually, physically, or developmentally disabled in a professional art studio space. Judith was not responsive until 1987, when visiting fiber artist Sylvia Seventy opened a new world of color, tactility, and communication to Judith. For the next eighteen years, until she died at the age of sixty-two entwined in her sister’s arms, Scott devoted hours each day to knotting, webbing, weaving, and tangling mysteries into works both large and small, using various fibers and materials. She embedded secret objects gleaned from the center and from home into the cavities of sculptures that might take hours, days, weeks, or months to complete. As she blossomed, Scott’s wrappings extended to her own person, which she encased in colorful headgear and clothes. Her vital works are cocoon-like specimens of color, complexity, and presence. They seem on the verge of metamorphosing into some remarkable life form, yet they will forever remain timeless, totemic, and inscrutable.

|

The School or arts/I couldn’t afford and for that I thank the lord/For what He has given me is the truth of His great love/For Him I worked and carved a stone and make a drawing and sing a song. —Consuelo González Amézcua

I was always a dreamer, and I am still painting my dream visions. —Consuelo González Amézcua

| |

Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua (1903–1975), Melcha Daughter of Salphahad, Del Rio, Tex., Mid-twentieth century. Ballpoint pen and pencil on paper; 18½ x 12¾ inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Evelyn S. Meyer (2005.10.6). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua was ten years old when she crossed the Mexican border from Piedras Negras, Coahuila, into Del Rio, Texas, with her parents and siblings. On November 27, 1913, against the backdrop of revolution and violent political chaos, the family struggled to make the transition from one reality to another, one border culture to another, from Mexican to American. After a period of transience, the artist’s father was hired as a bookkeeper, and they moved into a small house in a quiet neighborhood that remained the family residence throughout her life.

Chelo’s family held traditional expectations for their irrepressible child. Autobiographical statements suggest that she lived largely in her imagination. Completing only six years of formal education, González Amézcua was self-schooled in areas that interested her: history, art, architecture, and religion. She was a natural performance artist, dancing, singing, and playing the guitar, piano, castanets, and tambourine from an early age. Eventually, she also wrote and recited original poetry, carved stone, and drew the delicate “Texas filigree art” for which she is acclaimed today.

In 1932, González Amézcua was granted a scholarship to a renowned art school in Mexico. Sadly, the death of her father prevented her from accepting, and she soon started to work at the candy counter of the local Kress variety store. In 1964, she began to seriously draw, using ballpoint pen on cardboard or paper. The consistent line and ever-flowing ink permitted a fluidity in her mental recordatorio, or mental drawings, that evoke the intricacy of Mexican silver filigree work. Despite the fact that they are dense and tightly controlled images, the scrolling, curving lines also exhibit a free and joyous abandon in the feminine abundance of flowers, birds, graceful women, mythical figures, and fantasy architecture. Her spiritual nature sought expression in biblical subjects, such as this depiction of Milcah, one of the five beautiful daughters of Zelophehad, who lived during the time of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. As recounted in Numbers 27, Milcah and her sisters petitioned that they might inherit their father’s name and property. The Lord granted permission, provided they did not marry outside their ancestral tribe, a culturally insular narrative González Amézcua may have internalized as the daughter of two cultures. Crossing one border to another is not an erasure of where and what one has been; it is a melding of two existences. As a survivor of the mass deportations of Mexicans and Mexican American citizens during the 1930s and 40s, González Amézcua asks, “Mystery of life/Whose blood [in] her veins flow?”

|

“From sad experience I now have been unlawfully confined and otherwise barbacued by the Government going on twenty-three years while I am yet uncondemned by any witness of either friend or foe.…I was once taken before the Court without any warrant and sent to the House of Correction for the space of nine months without any trial.…Now the Seven Evil Confronting Spirits are…Knavery, and Slavery, and Pledged Secretiveness and Know Nothing Hypocrisy that forms the Grabbgame theology and the Ku Klux of Hell. Now these are the first four Inferior Evil Spirits and then to keep them in vogue it takes Wrath and Strife and bloodshed in War.“—Franklin Wilder

| |

Franklin Wilder (1813–1892), The Messiah’s Crown, State Hospital at Northampton, Mass., 1878–1882. Ink and pencil on paper, 15½ x 16¾ inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Philip M. Isaacson (1979.28.1). Helga Photo Studio |

This is one of two drawings signed by Franklin Wilder, a descendant of English dissenters who arrived in the American colonies in the seventeenth century seeking religious freedom. The copious texts that indicate a schooled intelligence are framed in fervent religious terms and constitute an impassioned indictment of government, judicial courts, bloody wars, the Know Nothings, and the Ku Klux Klan that together comprise the secret societies that control the lives of individuals powerless in their grip. Although the texts speak to a troubled mind and life, there is a foundation of truth to the conspiratorial tone.

The Wilder family was among the founders of Lancaster, Massachusetts, now forming parts of Clinton and Sterling. They were one of four families that established large homesteads and farms on the east side of the Nashua River. Following the death of Revolutionary soldier Stephen Wilder his three hundred acres were divided among his sons. It is this inheritance that descended to Franklin Wilder in 1834. Wilder was married the following year and soon had three children to support. As a yeoman farmer with few labor resources outside his own family, he struggled to manage the large farm and make ends meet. In 1842, the farm burned, and two years later Wilder’s property and that of neighboring farmers were appropriated by the Lancaster Mills, a powerful textile corporation that effectively destroyed the agrarian way of life that had persisted in this small corner of the state. In September 1855, Franklin Wilder was jailed over a dispute involving property rights. His incarceration, the loss of his family legacy, and other calamitous events proved too much. That same year, he suffered “delusions and insanity” and was committed to the Massachusetts State Hospital.

In 1859, Wilder was transferred to the new Northampton Lunatic Hospital facility, where he would live for the next thirty-three years until his death in 1892. The early years were modeled on guidelines of moral treatment and the benefits of physical labor. Working on the hospital’s farm provided activity, fresh air, engagement, and encouraged a sense of accomplishment and normalcy. For a time, Wilder drove an ox team and did some farming, but he gave this up when he became very religious, spending his time instead, reading the Bible, interpreting the Scriptures, and writing.

|

|

Ionel Talpazan (1955–2015), Untitled, (double-sided), New York City, August 4, 2004. Acrylic, felt-tip pen, and colored pencil on paper, 22 x 30 inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of James Wojcik (2016.10.1). Photo by Adam Reich. |

The defining moment of Ionel Talpazan’s life occurred when he was a young boy in his native Romania. Escaping into the night forest to avoid being punished by his foster parents, Talpazan believed he was suddenly engulfed by a celestial light, a “blue energy,” emanating from an aircraft hovering overhead. This otherworldly event transfixed him, and the possibility of alien technology ultimately became the theme of his many drawings that depict and deconstruct spaceships and unidentified flying objects with detailed descriptions and commentary written in Romanian.

In 1987, Talpazan escaped Romania by swimming across the Danube into what was then Yugoslavia. He lived in a refugee camp in Belgrade, operated by the United Nations, and was eventually granted asylum in the United States, becoming a citizen shortly before his death in 2015. Talpazan struggled in New York, finding it difficult to make ends meet and sometimes living on the street or in subsidized housing. But his vision and mission endured through all and any obstacles. His art was a quest for answers: “My art is about the big mystery in life. How did we get here on earth? Why are we here? Is there life on other planets?” A seeker and traveler, Talpazan used his art to ponder the universe: “My art shows spiritual technology, something beautiful and beyond human imagination, that comes from another galaxy.” In this double-sided work, Talpazan has arranged the planets spinning on concentric rings, like a diagram of the heavenly or celestial spheres, as the planetary model of the universe was once conceived.

|

American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection is at the American Folk Art Museum, Lincoln Square, New York City, through January 3, 2021. For more details of the exhibit visit folkartmuseum.org/exhibitions/american-perspectives.

Stacy C. Hollander is the curator of American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|