John James Audubon, Portraitist

Before John James Audubon (1785–1851) achieved international fame and financial success with the publication of his “double elephant folio” The Birds of America (1827–1837) and the smaller, but even more successful, octavo edition of that book a few years later, he struggled to make ends meet. He failed in several business ventures, and even spent a few weeks in debtors’ prison for his unpaid bills. During these lean years, he managed to generate a modest income by giving art lessons and making pencil, charcoal, chalk and oil portraits. Human portraiture was never something he particularly enjoyed, but the surviving examples of his work suggest that it might have given him a very different artistic reputation had he chosen to make it the focus of his career.

| |

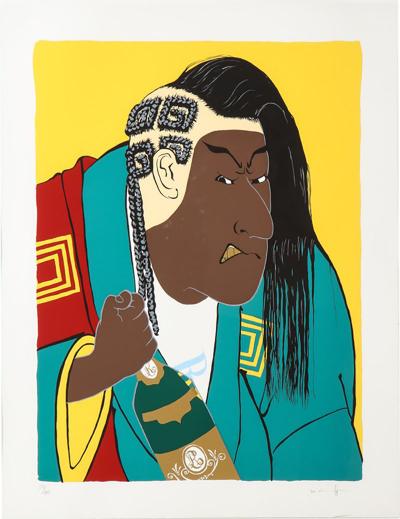

Fig. 1: John James Audubon (1785–1851), plate 83, “The House Wren,” The Birds of America (1827–1837). Hand-colored aquatint engraving, 39½ x 26½ inches. Courtesy of The National Audubon Society. |

The illegitimate son of a French sea captain, born in Haiti and raised in France, Audubon came to America in 1803 to avoid being drafted into Napoleon’s army. He brought with him a life-long love of birds and an innate talent for capturing their appearance on paper (Fig. 1). While living at Mill Grove, a property owned by his father twenty miles west of Philadelphia, he met and married his near neighbor, Lucy Bakewell, with whom he had two sons and two daughters, only the first two of whom lived to maturity. Within months of their wedding, the young couple moved south to Louisville, Kentucky, where Audubon was eager to try his hand at business.

A number of poor investments, and one failed venture after another put the Audubons in financial distress, forcing the quickly-Americanizing Frenchman to generate a meager income through odd jobs. He gave lessons in drawing, dancing, music, and fencing. He earned additional money by making chalk and pencil drawings of individuals in the wealthy families he met through the introduction of friends and his own initiative. By capitalizing on what he called “my little talents” in this way, he was able to make between five and twenty-five dollars per portrait. In some cases, he made the portraits in exchange for the hospitality of his sitters; in other cases, through barter for needed goods and services. The likenesses of his brothers-in-law Nicholas Augustus Berthoud and Thomas Woodhouse Bakewell (Figs. 2 and 3), may have been undertaken without charge.

|  |  | ||

(Left) Fig. 2: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Nicholas Augustus Berthoud, 1819. Charcoal, chalk and graphite on paper. 10 x 8 inches. Courtesy of J. B. Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY. (Center) Fig. 3: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Thomas Woodhouse Bakewell, inscribed “Louisville 1820 by Audubon.” Graphite on paper. 8 x 6 inches. Courtesy of Mill Grove, County of Montgomery, Pennsylvania. (Right) Fig. 4: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Self-portrait, Almost Happy, 1826. Graphite on paper. 5½ x 4 inches. Collection of the University of Liverpool Art Gallery. Courtesy of Bridgeman Images. | ||||

Some of Audubon’s money-making forays put stress on his marriage by keeping him away from his family for weeks and sometimes months at a time. His letters to Lucy during this period describing the charms of his female pupils and sitters—including one who requested her portrait be painted as a nude—could not have helped. The long-suffering Lucy, busy raising their two sons, added to the family’s revenue when she could by giving lessons in reading, writing, arithmetic, and music to the children of others.

Although Audubon preferred painting birds to people, he was remarkably adept at portraiture when the circumstances required. As his artistic reputation grew, he was called upon to make posthumous portraits or to capture the likenesses of people at the ends of their lives. “I was sent for four miles in the country, to take likenesses of persons on their death-beds,” he recalled in his memoirs, “and so high did my reputation suddenly rise, as the best delineator of heads in that vicinity, that a clergyman residing in Louisville … had his dead child disinterred, to procure a fac-simile of his face.” It was a grim profession, and not one Audubon was eager to pursue, but it did help tide him over until his self-financed bird book project could bear fruit.

|  | |

(Left) Fig. 5: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Mrs. Peter McClung, 1820. Charcoal and pencil on paper. 11¼ x 8¾ inches. Courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1973.32.2). (Right) Fig. 6: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Peter McClung, 1820 . Charcoal and pencil on paper. 11¼ x 8¾ inches. Courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1973.32.1). | ||

| |

Fig. 7: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Barbara Fontaine Cosby Todd, ca. 1819. Pencil, chalk and charcoal on paper. 10 x 17½ inches. Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY (1978.13.1). |

Because his ornithological illustrations have much more universal appeal, and because most of the chalk and pencil portraits he made have remained in private hands, his ability as a bird painter has dominated his reputation, while his role as a painter of human portraits is relatively little known. Based on references in his letters and journals, it is estimated that Audubon made more than one hundred human portraits between 1819 and 1826. He reports doing as many as fifty in 1821, and earning $220 in one ten-day period alone. Unfortunately, we know the whereabouts of less than a third of his portraits today.

The chalk portrait that is most frequently reproduced is the one he made of himself in 1826 in which he described himself as “almost happy” (Fig. 4). The other portraits we know about represent his family, friends, and the acquaintances he made in the South and Mid-West, especially during his time in or near Louisville, Kentucky, Natchez, Mississippi, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Cincinnati, Ohio.

In 1821, Audubon wrote his wife to report on his success as an art teacher and portraitist in New Orleans. “There are men here of talents in my line of focus who Draw and paint beautifully,” he wrote Lucy, “yet I am preferred….I have, I believe, not one adversary [competitor] in America.” Part of this self-aggrandizement was due to Audubon’s ego and his wish to reassure Lucy that he could support her and their growing family, but part of it was also due to his lack of familiarity with the greater artistic community within the United States. He had not yet met John Vanderlyn, who would later use him as the model for his portrait of President Andrew Johnson, or Thomas Sully, who would take him under his wing in Philadelphia in 1824. Other artists like Charles Willson Peale, and his son Rembrandt were painting masterful portraits of the leading figures in the new Republic up and down the East Coast at a time when Audubon was living hand-to-mouth on the country’s frontier. Fortunately for him, most of his patrons in Louisville, Natchez, New Orleans, and Cincinnati had little or no contact with other artists, and so considered Audubon a painter without equal.

-Sarah-Best_John-James-Audubon.png) | |

Fig. 8: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Sarah (Mrs. Thomas) Best , 1820. Graphite and black chalk on paper, possibly touched with a neutral wash. 11⅝ x 9⅝ inches. Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Watercolors and Drawings, 1800-1875. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (52.1564). |

It is unknown how Audubon taught himself to create his elegant portraits in pencil and chalk. In his memoirs, and when he was trying to promote his talents as a portraitist, he claimed to have received his artistic training from the renowned French painter Jacques Louis David (1748–1825), court painter to both Louis XVI and Napoleon, but there is no evidence to support this claim. It is possible that he was exposed to some of David’s work—and the work of other, equally talented European painters—either before traveling to America in 1803, or during his year-long return trip to France in 1805—but how much they influenced his artistic activity is hard to say.

In the United States he may have been influenced by the silhouettes cut by Moses Williams and others at Charles Willson Peale’s museum in Philadelphia, or the masterful black and white profiles and related prints of distinguished Americans by his French compatriot Charles Balthasar Julien Fevret de St. Mémin (1770–1852). Audubon’s earliest known portraits have the same strict profile compositions as these (Figs. 2, 5, 6, and 7). In time, he added strength and character to his subjects’ depictions by giving their faces a three-quarter angle view (Figs. 8–11). In his most powerful portraits, such as that of John Baptiste Bossier of 1821 (Fig.12), and Frederic Huidekoper three years later, his subjects look back and seem to make direct eye contact with the viewer. More often, his subjects have a distant stare, as if they are contemplating the world beyond what we can see.

|  | |

(Left) Fig. 9: John James Audubon (1785–1851), General William A. Lytle, Cincinnati, Ohio, October 1820. Graphite, chalk and charcoal on paper. 10 5/8 by 7 ¾ inches. Collection of Jenifer Newhall Saliba. (Right) Fig. 10: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Eliza Stahl (Mrs. William A Lytle), inscribed on verso: “Drawn by J.J. Audubon/ Cincinnati, Oct. 1820”. Graphite, chalk and charcoal on paper. 10⅝ by 7¾ inches. Collection of Jenifer Newhall Saliba. | ||

|  | |

(Left) Fig. 11: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Edmund Howard Wailes, 1822. Graphite and chalk on paper. Collection of Robert Pierpont. (Right) Fig. 12: John James Audubon (1785–1851), John Baptiste Bossier, 1821. Crayon and ink over graphite on paper. 12¾ x 9½ inches. Gift of Mrs. Elise Guignon Collins in memory of Barat Guignon. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri (60-44). | ||

|

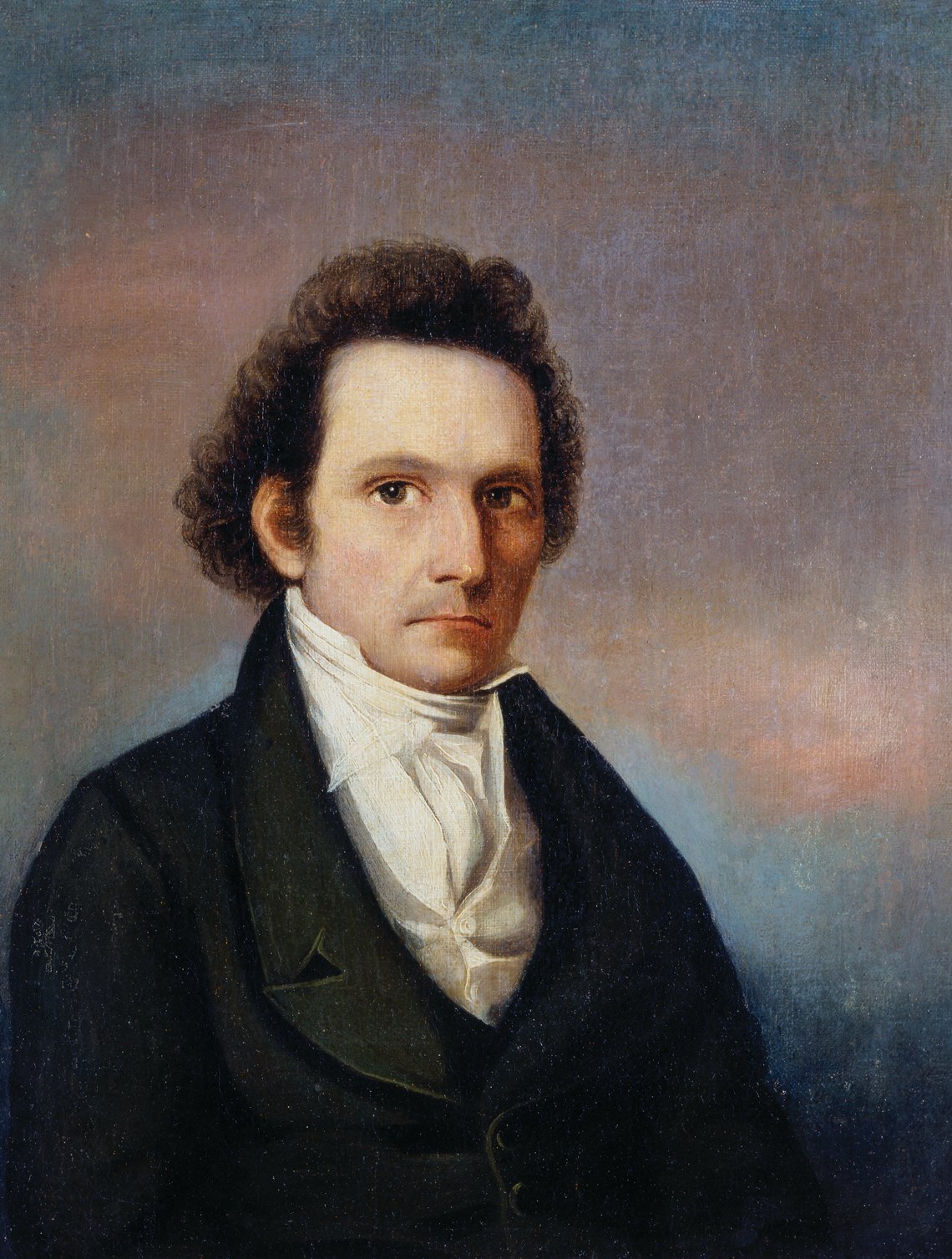

Fig. 13: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Self-portrait, 1822. Oil on canvas: 12½ x 10 inches. Private collection. |

| |

Fig. 14: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Victor Gifford Audubon, ca.1823. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of John James Audubon State Park, Henderson Kentucky, Kentucky Department of Parks (JJA.1941.84). |

In the autumn of 1822 Audubon met an itinerant portrait painter named John Steen from whom he received some basic instruction in painting in oils. For a brief period they formed a portrait-painting partnership. Despite his success with his chalk and pencil portraits, Audubon believed that oils were a more prestigious and more lucrative medium in which to work; he also thought the pencil and chalk drawings he had been making at such a steady clip were beginning to take a toll on his eyesight. “Although I now am the maker [of the] very best portraits [in chalk],” he wrote to Lucy in May 1821, “I would like to paint portraits in oil. I am now afraid that Black Chalk injures my Eyes that are always sore.” With the exception of an oil painting he made of himself shortly after receiving Steen’s instruction (Fig. 13), and a few others he made of his family at the same time (Fig.14). Audubon was not particularly adept in this medium. His pencil, chalk and charcoal portraits remain his strongest. Throughout his life, as he directed most of his artistic energies to birds, the medium with which he was most comfortable was watercolor, and yet, interestingly, there are no known portraits by Audubon that were painted in watercolor.

Mindful of the help his portrait painting had provided him during challenging times, Audubon asked Thomas Sully to give him instructions in oil painting when he was in Philadelphia in 1824. Sully agreed to do so in exchange for Audubon teaching his daughter, Sarah, how to paint with pastels and watercolor. By this time, however, Audubon was already so invested in painting birds for his great book on the subject that he was reluctant to turn back to portraiture in a meaningful way. After 1824, his portraits of people are few and far between. The portraits by Audubon that survive hint at what he might have been able to achieve had he chosen people over birds as his favorite subjects.

1. Victor Gifford (1809–1860), John Woodhouse (1812–1862), Lucy (1815–17), and Rose (1819–1820).

2. Letter from J. J. Audubon to Lucy Audubon, quoted in Stanley Clisby Arthur, Audubon: An Intimate Life of The American Woodsman (New Orleans: Harmanson, 1937), 183.

3. J. J. Audubon, “Myself,” published in: Maria R. Audubon, Ed, Audubon and His Journals, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897, Vol. 1, 36; also quoted in Alexander B. Adams, John James Audubon (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1966), 186–187.

4. Anette Blaugrund and Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. Eds., John James Audubon The Watercolors for The Birds of America (New York: Villard Books, Random House for the New York Historical Society, 1993), 70. J. F. McDermott speculated that Audubon could have drawn “several hundred” such portraits between 1819 and 1826. See McDermott, “Likeness by Audubon,” Antiques (June 1955): 501.

5. In a journal entry of October 25, 1821, Audubon noted that he had done 50 portraits since October 12, 1820. See Edward H. Dwight, Audubon Watercolors and Drawings (Utica NY: Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, 1965), 27. For the amount he earned, see William Souder, Under A Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2014), 178–179.

6. Letter from J.J. Audubon to Lucy Audubon, from New Orleans, May 24, 1821. H.F. DuPont Winterthur Museum Library, Archive, Col. 170 87X001.

7. Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon The Making of an American (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 214–15.

8. Letter from J.J. Audubon to Lucy Audubon, from New Orleans, May 24, 1821. Winterthur archive Col. 170 87X001.

9. His own self-portrait, at age 37, was painted at Beech Woods, Feliciana Parish, Louisiana in 1822.

Robert McCracken Peck is Curator of Art and Artifacts and Senior Fellow at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

|

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|