In American Waters

|

|

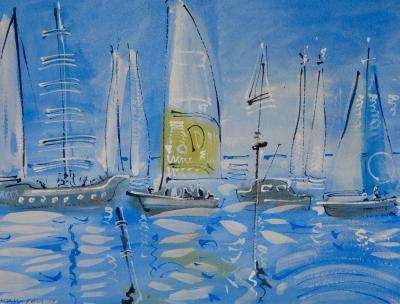

merican artists have captured the beauty, violence, poetry, and transformative power of the sea for more than 250 years. Their paintings shape our perceptions of the sea and engage our emotions, whether depicting the open ocean or waves crashing on shore, a ship in the midst of battle, or a yacht in racing splendor.

|

In American Waters, co-organized by the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, features a diverse range of modern and historical artists. The exhibition embraces a superlative group of traditional marine works by painters like Fitz Henry Lane and James Edward Buttersworth at its core, but quickly turns to embrace an expansive notion of what constitutes a marine subject in American art. Works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Amy Sherald, Kay WalkingStick, Norman Rockwell, Hale Woodruff, Paul Cadmus, Thomas Hart Benton, Jacob Lawrence, Valerie Hegarty, Stuart Davis, and many others, each explore a facet of personal experience and perspective on America’s relationship with the sea. The works gathered for the exhibition, from America’s early days to the contemporary era, convey powerful origin stories and everyday scenes. They emphasize our individual and collective experience and deepen our understanding of the sea as a symbol of national opportunity and invention.

In American Waters reveals that marine painting is so much more than ship portraits. Through more than ninety works, the exhibition traces changing attitudes about the symbolic and emotional resonance of the sea in America and how contemporary perspectives are informed by marine traditions. Visitors will discover the sea as a thematically rich way to reflect on American culture and environment, learn how coastal and maritime symbols moved inland across the United States, and contemplate what it means to be “in American waters.”

Collaborative and interdisciplinary, In American Waters combines art history, maritime history, and even nneuroscience to create a more expansive and inclusive vision of the role of the marine in American painting, one that encompasses greater geographic breadth and a multiplicity of artists and artistic expression. To these ends, this exhibition is the first to grapple with how attitudes about the sea may manifest in works that are not traditional seascapes.

Instead, the experience offers deeply emotional explorations of industry and political conflict, sailor culture, visions of the undersea world and abstraction, as well as legacies of the Middle Passage and immigrants’ points of entry.

Even before marine art was produced in America, seascape paintings were included among items imported from Europe to decorate American homes in the latest style. Later, artists developed a distinctively American vision of the sea with an independent artistic identity.

Today the sea is on the minds of Americans, in part, because of sea-level rise and the impact of associated climate events on coastal communities and beyond. More than 90 percent of the world’s commerce travels by sea and it is no coincidence that most major American cities are situated on waterways—whether around protected coastal harbors or inland at the confluence of major rivers. No matter where we live, the sea shapes all of our lives and continues to inspire some of the most exciting artists working today.

Founded in 1799 by the East India Marine Society in Salem, Massachusetts, PEM developed one of the nation’s first and foremost maritime collections. Situated on one of New England’s most historic harbors, the museum has long stewarded and celebrated the interplay of maritime history and global interconnectivity. Exhibition co-organizer, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, was founded in 2011 in the Ozarks. The region surrounding Bentonville, Arkansas, is known for its abundant waterways in the form of springs, creeks, lakes and rivers, most notably the White River that originates from the Boston Mountains of Northwest Arkansas and ultimately feeds into the mighty Mississippi River, which flows to the Gulf of Mexico.

|

|

Michele Felice Cornè (1752–1845), Ship America on the Grand Banks, about 1800. Oil on canvas, 39¾ × 56 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Mrs. Francis B. Crowninshield (1953, M8257). |

The first artist in the United States to declare a specialty in marine subjects was Michele Felice Cornè. Cornè left Naples on Elias Hasket Derby’s ship, Mount Vernon, in 1799, bound for Salem, Massachusetts. Upon arrival, he became a kind of artist-in-residence to the local shipowners, painting vessel portraits and historical and allegorical images in oils and gouache, leading the Reverend William Bentley to comment, “Mr. Cornè continues to enjoy his reputation as a painter of ships. In every house we see the ships of our harbour delineated for those who have navigated them.”

Cornè’s Ship America on the Grand Banks depicts the first of four ships so named by Salem’s Crowninshield family between Independence and the War of 1812. It was the last British war prize taken by colonial privateers during the American Revolution. Cornè portrays the renamed ship in the international waters of the Grand Banks fishing grounds off of Newfoundland amid French and British flagged vessels. The history of the ship and its prominent American flag, set within a competitive commercial setting, evokes pride in the new nation and its emerging international profile.

|

Artist from United States, after Captain Charles Wilkes (1798–1877), USS Vincennes in Disappointment Bay, about 1842. Oil on canvas, 23½ x 35½ inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Museum purchase, 1902 (M265). |

|

Titian Ramsay Peale (1799–1885), Town of Mathwalta / Island of Venua Levul Viti’s / US Ship Peacock, 1840–49. Oil on wood, 10 × 14 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Mrs. Anna Glen Butler Vietor, 1984 (M20223). © 2020 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola. |

The United States Exploring Expedition (1838–42) was intended to establish the country as a global naval power and world-class scientific authority. Artwork produced on the expedition visualized America’s expanding territorial and political interests in the Pacific. The expedition left Hampton Roads, Virginia, with six naval ships carrying more than 340 sailors, scientists, and artists for a four-year voyage to traverse the Southern Pacific region. The painting of the flagship USS Vincennes amid giant icebergs and a menagerie of Antarctic sea creatures in an unpeopled wilderness portrays the process of territorial discovery as the expedition provided evidence that Antarctica was indeed a continent.

In contrast, the view from a ship’s deck as the expedition arrives at a busy harbor suggests a scene in the Fiji islands devoid of any impact from prior American voyages there. US merchants had been living and trading in Fiji since the 1810s, exchanging sandalwood for guns and creating political alliances that pitted one chief against others for Americans’ strategic gain.

|

Edward Ludlow Mooney (1813–1887), Portrait of Ahmad bin Na’aman, 1840. Oil on canvas, 41¼ × 35½ inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Mrs. William P. McMullan (1918 M4473). ©Peabody Essex Museum; Photography by Jeffrey R. Dykes. |

In the spring of 1840, al-Sultanah, the first Arab vessel to visit the United States, sailed into New York Harbor with great fanfare. The diplomatic and popular center of attraction on board was Na’aman, the private secretary and emissary for Sayyid Sa‘īd, sultan of Oman, Muscat, and Zanzibar.

To commemorate the visit, the American artist Mooney painted this work for Na’aman. A double portrait of man and ship, it signifies the personal relationships integral to the success of America’s emerging global trade partnerships. The New York Common Council also commissioned Mooney to paint a likeness of Na’aman for New York City Hall. The portrait still hangs there today.

|

Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865), Southern Cross in Boston Harbor, 1851. Oil on canvas, 25¼ × 38 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Stephen Wheatland, 1987 (M18639). © 2020 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola. |

A typical ship portrait, like that of a person, is a carefully constructed composition with common features. A vessel is placed in a specific situation, and artistic skill combines with nautical accuracy to document maritime culture in a distinctive way. In that tradition, Lane captures the characteristic details of the clipper Southern Cross built for the California gold rush. By showing the ship at a slight angle and highlighting the naturalistic setting of Boston Harbor, he brings to the fore a marine backdrop resembling one that might be seen in the portrait of a ship captain.

|

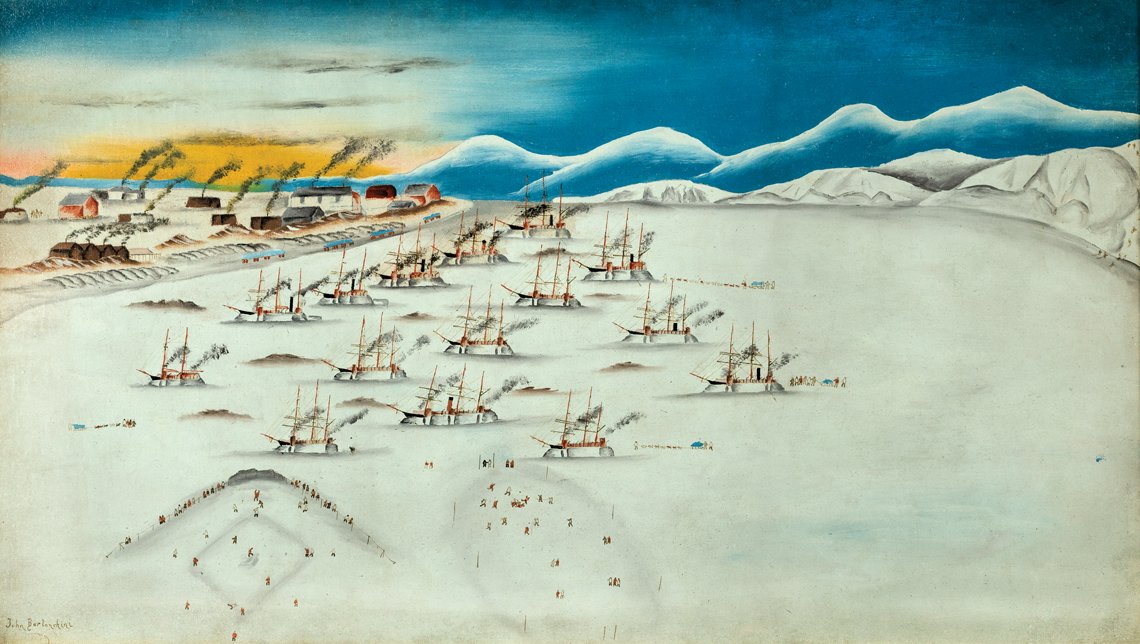

John Bertonccini (1872–1947), Whaling vessels in the Ice, Herschel Island, about 1894–1895. Oil on canvas, 18 × 31 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Purchase with funds donated by the Maritime Art and History Visiting Committee (2019.33.1). © 2020 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola. |

Bertonccini’s vision of the remote American whaling station at Herschel Island, off the north coast of Canada’s Yukon, reflects a navigator’s vision of the rigors of life. He lays out activities as on a sea chart, floating amid an otherwise white and featureless field that highlights the stark bitterness of the locale. Hundreds of men, some traveling with families, made the long voyage around Alaska, intentionally freezing their ships into the ice to pass the winter there to avoid a lengthy seasonal round trip. While frozen in, they held concerts, theatricals, and sporting events. Bertonccini said, “Imagine baseball at 50 below zero, played by moonlight, with the players in fur uniforms!”

|

William Bradford (1823–1892), Icebound Ship, about 1880. Oil on canvas, 30 × 48⅛ inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Museum purchase with funds from anonymous donor, 1996 (M27190). ©2020 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola. |

The occasional voyage organized specifically to serve the purposes of art contrasts with the more common practice of art in service of an expedition. Bradford undertook six voyages to Labrador and one as far as Greenland to make firsthand observations of the environment and life in high latitudes. His paintings are distinctive for the subdued tones and mystical optical effects unique to the polar atmosphere. He never witnessed ships caught in the ice, but he was taken by seal hunters’ stories of the spring 1863 season when the wind shifted and nearly 40 vessels became trapped amid the ice fields and were quickly crushed.

|

James Edward Buttersworth (1817–1894, born in the United Kingdom), Yacht Racing off Sandy Hook, about 1877. Oil on canvas, 20 × 36 inches. Collection of Alan Granby and Janice Hyland. |

|

Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), Pertaining to Yachts and Yachting, 1922. Oil on canvas, 20 × 24 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art; Bequest of Margaretta S. Hinchman (1955-96-9). |

Buttersworth highlights the fluid motions of three yachts through his use of large semicircles and overlapping arcs, evoking the excitement of a critical moment in a race when boats round a lightship and change tacks. The precisely set and billowing sails of the foreground schooner propel the dynamic scene, with every inch of the painted canvas conveying vibrancy and motion. A master technician, Buttersworth accurately captured fine details in his portraits as seen on the schooner at the center “Magic,” winner of the first America’s Cup in 1870. Heeling toward the viewer, the artist depicted the individual planks on the deck and deck structures, including the grating at the bow. The figures on all three boats are well defined and the sails are accurately rendered with highly detailed sail seams and reef points.

In his modernist reimagining, Sheeler distills the essence of such realistic yacht racing scenes by stripping out the specificity while imparting the emotional impact. He accentuates motion to capture the vitality of several boats in a composition that pushes such imagery almost to the point of abstraction.

|

Childe Hassam (1859–1935), East Headland, Appledore, Isles of Shoals, 1911. Oil on canvas, 30 × 36 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Peter S. Lynch in memory of Carolyn A. Lynch (2018.72.1). Photography by Kathy Tarantola. |

Hassam’s impressionist technique belies a steadfast accuracy derived from thirty summers spent on the Isles of Shoals, a group of small islands located about nine miles off the coast of southern Maine and New Hampshire. His record of identifiable rock formations and waterline marks has enabled scientists working on Appledore today to corroborate continuity and change relative to modern-day marine ecology and climate.

|

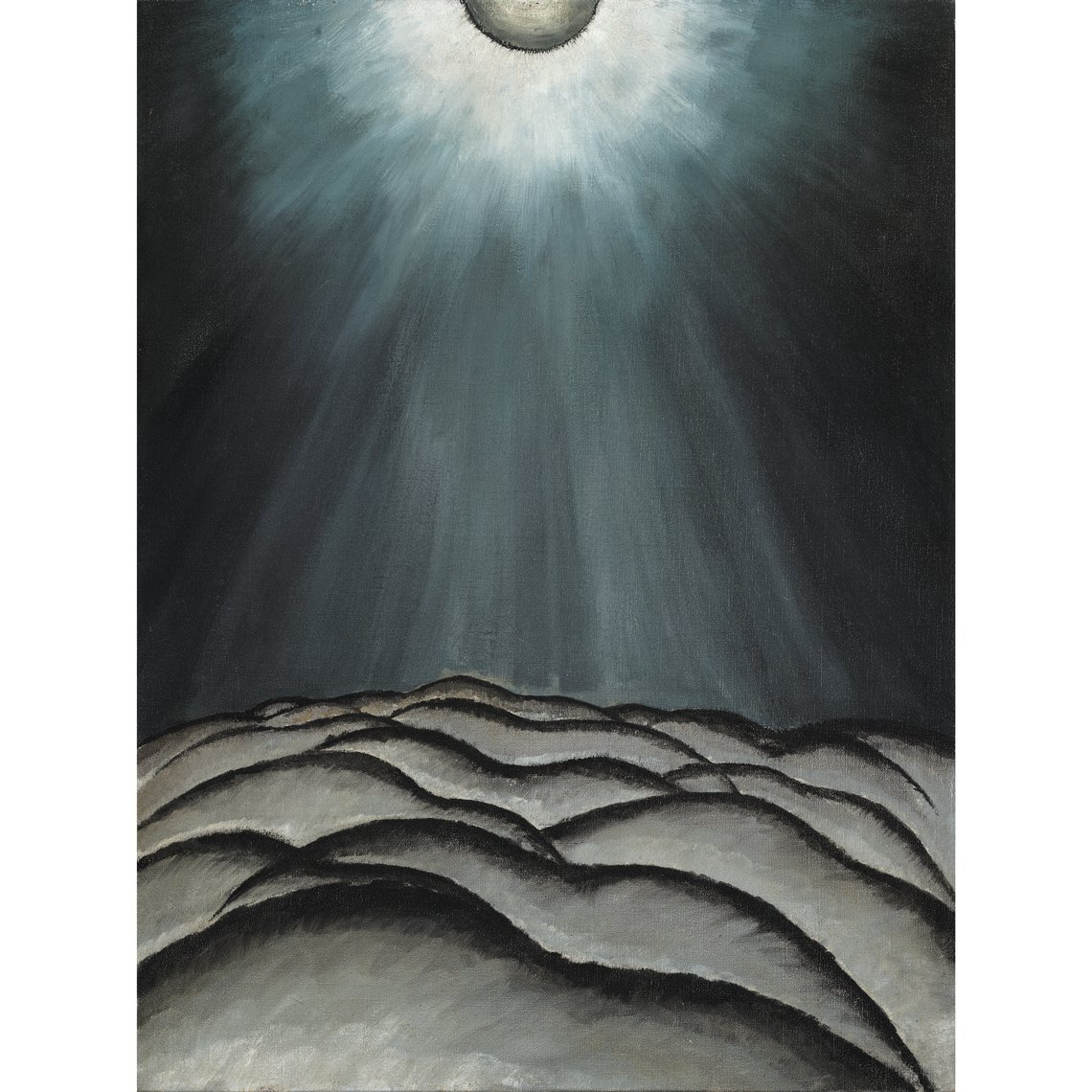

Arthur Dove (1880–1946), Moon and Sea No. II, 1923. Oil on canvas, 24 × 18 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Photography by Robert LaPrelle. |

Dove spent years living on a boat on Long Island Sound, where he gained intimate knowledge of the sea. His experience of a ferocious storm motivated him to create this work. He wrote to his dealer Alfred Steiglitz: “It is now 3:45 a.m. in the midst of a terrific gale . . . Have been trying to memorize this storm all day so that I can paint it.” Ominous black outlines of swelling waves rise to conceal the horizon, making the scene “too dark and nerve strained” at first to paint. After the storm, Dove looked to the luminous rays from the partially obscured moon and saw “storm greens and storm grey” illuminated in the aftermath.

|

Theresa Bernstein (1890–2002, born in Poland), The Immigrants, 1923. Oil on canvas, 40 × 50 inches. Collection of Thomas and Karen Buckley. Image courtesy of Woodmere Art Museum. |

Bernstein’s bustling deck scene captures the experience of traveling to America in steerage class. She visualizes the busy clamor and the occasion for individual introspection on a long voyage. The figure in the center foreground is thought to be Bernstein herself, holding her only daughter, who had died in 1920 at three months old. It is also possible that Bernstein was reflecting upon her own youthful emigration from Poland on the SS Elbe at age two. The painter’s contemplative view encapsulates the emotional weight of generations of people voyaging across the ocean to make a new life.

|

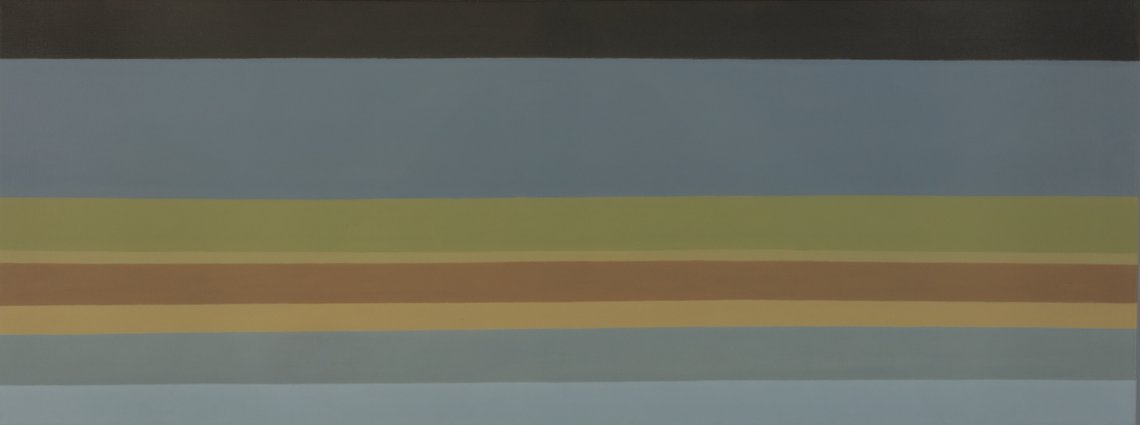

Felrath Hines (1913–1993), Untitled, 1967–73. Oil on canvas, 27 × 71 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Dorothy Fisher, widow of the artist (2014.59.2). |

Hines was inspired by the beaches of Chincoteague, Virginia, to present a mirage-like oceanic and atmospheric bands in pure horizontality. This work emphasizes his interest in the planar and abstract properties of light and water. Layered above two blue-gray horizontal stripes are bands of varying thickness and colors evocative of a beach’s shallow water with sandy surfaces below—ocher, brown, beige, and pale green. The wide planes of color also direct the eye toward the stark horizon at the top of the painting: a weighty strip of leaden sky edging down against the gray ocean.

|

In American Waters is organized by the Peabody Essex Museum and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The exhibition is accompanied by the catalogue In American Waters: The Sea in American Painting, edited by Daniel Finamore, PEM’s Associate Director—Exhibitions and The Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History, and Austen Barron Bailly, Chief Curator at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The exhibition will be on view at the Peabody Essex Museum (pem.org) from May 29 through October 3, 2021 and travel to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (crystalbridges.org), where it will be on view November 6, 2021 through January 31, 2022.

Austen Barron Bailly is Chief Curator at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. At the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., are Sarah Chasse, Associate Curator for Exhibitions and Research, Daniel Finamore, Associate Director—Exhibitions and The Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History, and George Schwartz, Associate Curator for Exhibitions and Research.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|