A Collection of Collections: The American Folk Art Museum Celebrates Its 60th

|

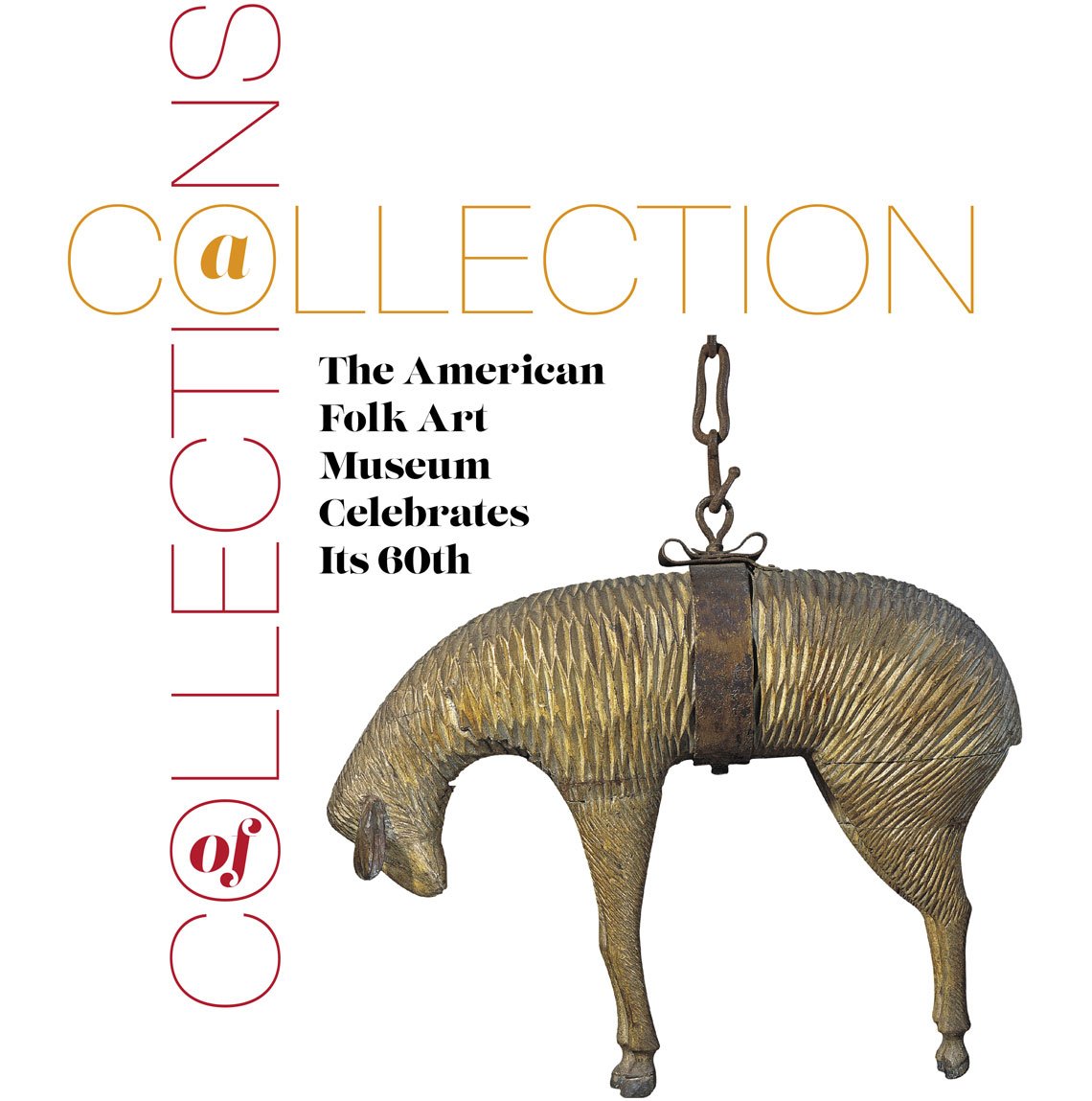

Fig. 1: Hanging sheep shop sign, by unidentified artist, Northeastern United States, Canada, or England, mid-19th century. Paint and traces of gold leaf on wood with metal. H. 33, W. 38, D. 9 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Ralph Esmerian (2005.8.57). Photo by Olya Vysotskaya. Emblematic trade (shop) signs date back to Medieval Europe and even the ancient world. Especially when literacy was not commonplace, a large and well-executed sign served as an essential mode of communication as well as an attention-grabbing ornament. Easily interpreted symbols—such as a sheep for a tailor or wool dealer or a tooth for a dentist and—instantly advertised the purpose of a business to passers-by. In the early twentieth century, Americana collectors began to recognize the appeal of trade signs as sculptural objects that also told a story of the Unites States’ energetic entrepreneurial culture. Within the history of folk art as a developing collecting category, carved trade signs were identified alongside weathervanes and wildfowl decoys as significant contributors to an American tradition of sculpture that had typically been overlooked by the academic art historical canon. Key early collectors such as Electra Havemeyer Webb, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, and Adele Earnest—a founder of the American Folk Art Museum—made trade signs essential to their collections. |

by Emelie Gevalt & Valérie Rousseau

| |

Fig. 2: Center star quilt, by unidentified artist, New England, 1815–1825. Glazed wool, 100½ x 98 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Cyril Irwin Nelson in honor of Robert Bishop, director (1977–1991), American Folk Art Museum (1986.13.1). Dazzlingly diverse quilts comprise one of the largest sub-collections within the Museum’s holdings. These skillfully-crafted textiles offer an unusually broad record of American women’s history—representing a multitude of voices that are so often left out of the documentary archive. The quilts in the exhibition represent quilting practices from early nineteenth-century New England to the late twentieth-century South. |

Whereas the Western history of fine art has had a long-established hierarchy of artistic media and subjects, the boundary-breaking modernist movement during the early twentieth century changed popular understandings of what could be considered art. “Folk art,” and later, “self-taught art” and “art brut,” emerged as new frameworks. Even though their definitions were imperfect and carried forward biases of their own, these developing fields made space for creative expressions typically excluded from the art historical canon.

Many of these objects were seen as “rediscoveries”: shop signs and bedcovers (Figs. 1, 2), originally made for functional purposes, were freshly appreciated for their craftsmanship and visual power; the works of self-taught artists, previously limited to local or family audiences, were exposed to a wider community of art lovers. Collectors developed expertise in concert with the greater recognition of makers, delving deeper into object histories as more material was brought into the marketplace.

Some of the first objects to enter the American Folk Art Museum’s (AFAM) holdings represented touchstones of the invention of the folk and self-taught fields. Works seen in Multitudes (on view until September 5, 2022), such as selections of wildfowl decoys, needlework, and quilts, exemplify the iconic status now afforded to certain folk art categories due to their craftsmanship and striking graphic appeal. The exhibition, which celebrates the Museum’s 60th anniversary, brings approximately 400 works together in non-chronological order, visually clustered to reveal their individuality as well as their commonalities.

The concept of multitudes, reflected in the artistic process, from repetition and seriality, as well as in organizing acts of systemization, memorialization, and other areas of focus, illustrates how the Museum’s holdings truly comprise a collection of collections, as reflected in the themes of Memory Keepers, Repetitions, Systems, and Casts of Characters.

|

Memory Keepers

Early American objects like birth and marriage records, mourning pictures, family trees, and needlework samplers (Fig. 3), are especially redolent of memory-keeping—all serving as devices for documenting lives. Although the names and dates have lost much of their personal context outside of the families who created them, as part of the Museum’s collection, these works serve a broader cultural purpose. On public rather than private domestic display, such objects function as powerful symbols of connection to a larger past, evoking the presence of the multiple hands that have made, repaired, and handled them.

Mary K. Borkowski’s (1916–2008) “thread paintings” contain more complexity than meets the eye. During her lifetime, it was often assumed that her work was done with the latest in embroidery machine technology. “These pictures are not embroidery,” she said, “but more like low relief sculpture, and require hundreds of hours to create.” Each contained three or four layers of material, including canvas, batting, and muslin. Her practice drew on various techniques she had mastered, from needlework to crochet, appliqué, and quilting. Each laborious composition serves as an intricate recording of the artist’s emotions and personal history. A domestic abuse survivor, many of her paintings memorialize struggles, injustice, and traumatic events.

|  |

Fig. 3 (left): Sampler, Ruthy Rogers (1778–1812), Marblehead, Mass., ca. 1789. Silk on linen, 10½ x 9 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Ralph Esmerian (2005.8.53).

Few records survive of early American girls’ lives. Samplers and needlework pictures are rare material manifestations of their daily experience. Through the repetitive movements of sewing, the makers of these works of art actively embodied values of diligence and patience . . . stitch after stitch after stitch. While these objects were made in part as evidence of a girl’s industry, accomplishment, and taste, they now bridge the gap between history and the present through arresting color, texture, and pattern, as well as recorded dates and names. As an expression of shared identity and taste, needleworkers and their teachers created compositions that were variations of common themes, seen in the reiteration of houses, rolling hills, prettily dressed figures, and abundant plants and animals.

Fig. 4 (right): Sunburst, John Scholl (1827–1916), Germania, Pa.,1907–1916. Paint on wood with wire and metal. H. 71, W. 38, D. 24½ inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Cordelia Hamilton in recognition of research, work, and continued meritorious contributions in the field of 18th- and 19th-century American folk art by Mrs. Adele Earnest, founding member of the Museum (1982.8.1).

Extending outward in all directions, this exuberant Sunburst by John Scholl seems to radiate with a multitude of creative possibilities. After a lifetime working as a carpenter, the German-born immigrant to Pennsylvania took up sculpture when he was in his eighties. Over a decade, Scholl made approximately forty-five works of art, leaving behind the utilitarian aspect of his profession to revel in the pure pleasure of creation. His sculpture evokes a sense of dazzling abundance and deep satisfaction in craftsmanship, reiterated through multiple layers of symmetry, pattern, and embellishment.

“When a man works steadily and faithfully for sixty years, idleness is an unwanted stranger.”

— John Scholl

Repetitions

Repetition implies familiarity, comfort, and the soothing effects of the creative process (Fig. 4). However, if rote repetition pejoratively alludes to an impoverishment of inspiration, the act of repeating or “saying over again” can also reflect an obsessive search for excellence and innovative outcomes, or a persistent way to inscribe a concept. Sometimes it is only by looking at a large inventory of works created over a long period of time that we can perceive subtle progressions and artistic evolutions. As artist Yayoi Kusama puts it, the “more we look at one thing, the more we come to know that thing and the more we can see the infinite variety it can offer.” In the realm of one artist’s visual language, figures of repetitions determine a distinctive signature.

|

Systems

A system is an organized mechanism—a whole compounded of parts; a repository united by a conceptual framework. It is a recorded inventory of observations, experiences, factual events, and principles to which an artist can refer. It is conceived to give structure, control, and order, but also to bear witness, share, and persuade about the importance of advancing a particular kind of knowledge.

In early American material culture, tree-of-life imagery, an archetype with ancient religious and folkloric origins symbolizing fertility and immortality, was often used to decorate “moveable” goods—the kinds of textiles and furniture that were passed down from mother to daughter. Flourishes of flowering, fruitful vines, and branches may have been considered especially appropriate for a bride or young mother beginning a family of her own. In the case of the bed rug by Deborah Leland Fairbanks (1739–1791) and an unidentified family member, the carnation, an ancient emblem of love, adds further strength to the familial symbolism of unfurling branches (Fig. 5). The blanket chest, circa 1690–1720, by an unidentified maker (Fig. 6) may have itself been used to store decorated textiles, compounding the meaning of the blossoming vines extending across the wooden surface.

|  |

Fig. 5 (left): Bed rug, Deborah Leland Fairbanks (1739–1791) and unidentified family member, Littleton, N.H., 1803. Wool, 100 x 96 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Cyril Irwin Nelson in honor of Joel and Kate Kopp (2004.14.3).

Fig. 6 (right): Chest over drawer, by unidentified artist, Guilford-Saybrook area, Conn.,1690–1720. Paint on oak and pine. H. 41, W. 46½, D. 20¾ inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of the Historical Society of Early American Decoration (58.33).

|

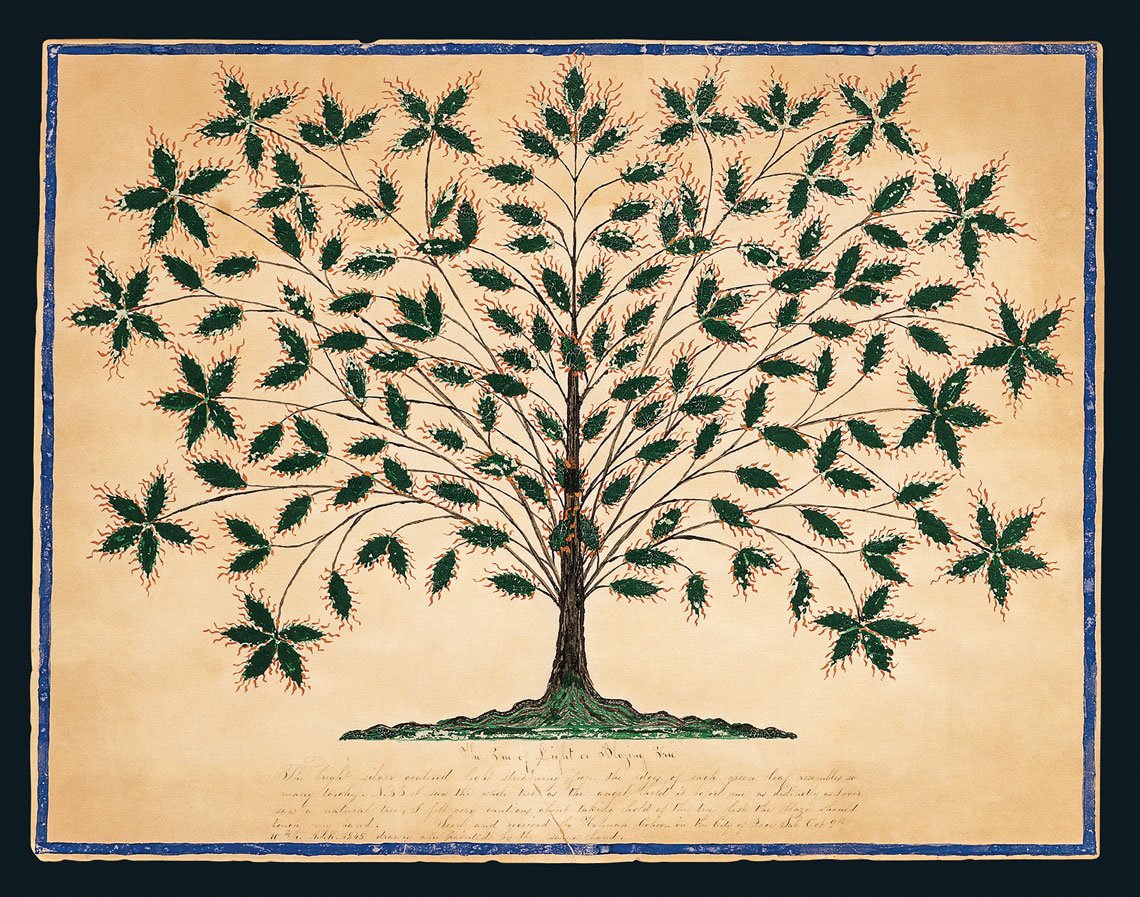

Fig. 7: The Tree of Light or Blazing Tree, gift drawing, Hannah Cohoon (1788–1864), Hancock, Mass., 1845. Ink, pencil, and gouache on paper, 16 x 20⅞ inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Ralph Esmerian (2013.1.3).

| |

Fig. 8: William A. Hall (1943–2019), Tree Motel, Los Angeles, Calif., June 5–13, 2009. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, 17 x 14 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; anonymous gift (2021.1.2). |

In the mid-nineteenth century, Shaker community member Hannah Cohoon (1788–1864) captured the spiritual dimension of the tree of life. Like other “gift drawings” created within this religious group, Tree of Blazing Light (Fig. 7) was believed to be a response to a divine vision, bestowed on the maker by a spirit guide. Cohoon’s image is a testament to the enduring power of the tree of life as a sacred but highly recognizable symbol. This imagery operated across cultures and is also evoked by the colorful bird trees often made within Pennsylvania German communities to celebrate births.

Artist William A. Hall (1943–2019) composed his drawings on the steering wheel of his car, in which he lived in and around Los Angeles for most of the last twenty years of his life. Hall conceived his drawings in series over a few days, months, or years, building visual narratives that developed on separate pages—not necessarily sequentially—of scrapbooks. They range from two to twenty panels, laid out and assembled after the fact by collectors. Hall’s art immerses us into the atmosphere of post-apocalyptic, unpopulated futuristic scenes, out-of-time Lilliputian detailed landscapes showcasing imposing twisted trees (Fig. 8), waterfalls, rocks, and wood machines of his invention. His production repeatedly tackled the interconnected themes of survival and safety.

|

|

Fig. 9: Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog, Vicinity of Amenia, N.Y., 1830–1835. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Ralph Esmerian (2001.37.1). |

| |

Fig. 10: Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), Portrait of Frederick A. Gale, Galesville (now Middle Falls), N.Y., ca. 1815. Oil on canvas, 44¾ x 24¼ inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Lucy and Mike Danziger in honor of Peter Tillou, Jason Busch, and Emelie Gevalt for their contributions to the appreciation of American Folk Art (2022.1.1). |

Cast of Characters

Entire worlds come alive under the artist’s hand, revealing myriad characters, both real and imagined. Artworks from artists as diverse as Ammi Phillips, Joseph H. Davis, Sam Doyle, and Mary Paulina Corbett conjure a wide range of personalities carefully depicted, dressed, named, and contextualized in their daily lives. These serial works—such as oil portraits, watercolors, and photographs—incorporate elements of consistency across time and place.

Early American portraits were intended to capture individual likenesses. At the same time, the commonalities between examples of this form can be striking, forging visual connections between sitters through the use of comparable formats, poses, clothing, accessories, and facial expressions. These distinctions and similarities convey a desire to ally oneself with like-minded community members, even in the course of expressing individuality. They can also demonstrate an artist’s wish to please their patrons, creating a composition with well-practiced components that could be executed with confidence and efficiency.

Ammi Phillips (1788–1865) painted hundreds of likenesses over the course of his decades-long career, working in the rural towns along the borders of New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Even as his compositions sometimes had standardized elements, the artist’s talent at capturing emotion allows each portrait to speak powerfully for itself. Phillips’ depictions of children are especially evocative and beloved. The Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog (Fig. 9) was made in the 1830s and forms part of a group of several portraits of similarly dressed children, in which tenderness of expression comingles with boldness of color and form. The Portrait of Frederick A. Gale (Fig. 10) is a highly unusual example of Phillips’ full-scale compositions, with the vibrant greens and reds of the boy’s clothing set strikingly against an ethereal pale background characteristic of the artist’s earliest works. The luminescent work speaks to Phillips’ uncanny ability to capture the beauty and emotional power of a child’s simultaneous innocence, mystery, and liveliness.

In the nineteenth century, a number of popular portraitists worked in watercolor, creating small-format likenesses that were more affordable and efficiently executed than large, slow-drying works of oil on canvas. New Englander Joseph H. Davis (1811–1865) consistently showed his sitters in profile, creating a sense of shared taste through the use of brightly patterned rugs and grain-painted furniture, both prevalent in households of the time (Fig. 11). Spouses Samuel Addison Shute (1803–1836) and Ruth Whittier Shute (1803–1882) developed a system for working together: she created the drawings while he executed the coloring.

|

Fig. 11 (left): Samuel Addison Shute (1803–1836) and Ruth Whittier Shute (1803–1882), Master Burnham, Probably Lowell, Mass., ca. 1831–1832. Watercolor, gouache, pencil, and ink on paper, 27½ x 19 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Ralph Esmerian (2013.1.13). Fig. 12 (right): Photographer unidentified, “Untitled (Photo booth portrait),” United States, ca. 1915–1969, Hand-tinted photograph, 4¾ x 3¼ inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Peter J. Cohen (2020.23.86). |

Among the Museum’s collection are photographs taken and developed with a photobooth, subsequently hand colored. The history of photobooths has been traced to the early twentieth century, when an American-Siberian inventor, Anatol Josepho, introduced the photobooth to New York City audiences through his studio named Photomaton. Photobooths became an instant novelty, with widespread popularity. Attendants in these early photobooth studios would welcome customers, seat them, and later urge them to pick a favorite photo from the photobooth strip to have enlarged or hand-tinted at the studio. When photobooth technology improved, costs decreased, and they became more widespread. Specialty photobooth studios and attendants gradually left the market, and thanks to automation, the photobooth experience evolved into a more a private affair. Customers could hand-color the photographs themselves, using tools like the Peerless or Volex kits. Through factors the customer could control, like their own poses, and the ability to hand-tint their photographs themselves, a photobooth subject could become part of the artistic process and make these images their own.

|

Emelie Gevalt is Curator of Folk Art and Valérie Rousseau is Senior Curator of Self-Taught Art and Art Brut at the American Folk Art Museum, New York City. They curated the exhibition, Multitudes. For more information, visit folkartmuseum.org.