Celebrating 250 Years of American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine

This archive article was originally published in the 14th Annivesary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Depictions of food, drink, and where we consume them have long fascinated American artists. While they used food to express creative concerns, their integration of culinary imagery into portraits, still lifes, and narrative scenes have also conveyed American pride of product, economic ambitions, moral beliefs, political views, and social messages. The exhibition Art and Appetite: American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine explores the rich tradition of food in American art from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. Sixty-five paintings present themes that include the important role agricultural bounty played in the success of the early Republic; the Victorian-era attraction to excess; debates over temperance and the changing roles of women; the rise of restaurant culture; and the impact of changes in agricultural science, transportation, and technology, including hybridization, importation, refrigeration, and mass production.

This painting is part of Norman Rockwell’s series The Four Freedoms, based on the four essential rights—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—outlined by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his 1941 State of the Union address. Rockwell’s “Thanksgiving Picture,” as this work came to be known, depicts the turkey and the holiday as a symbol of American values. Oddly, this middle-class family’s meal is limited to turkey, celery, a vegetable in a covered bowl, fruit, and water. Perhaps the meager menu reflects wartime rationing, which limited the sale of sugar, butter, and other items. The beautifully browned bird is positioned at the apex of the composition, presented by the matriarch while her husband waits to do the carving. The picture thus visualizes ideals of home and family while echoing government campaigns encouraging women to do their part by nurturing the nation’s working men.

After World War II, the turkey became the symbol of the Thanksgiving holiday. Here, Roy Lichtenstein’s oversized turkey fills the entire canvas, a cartoonish icon of the American feast. The artist rendered the bird with thick black outlines and a uniformly golden color that evokes modern advertising’s emphasis on appearances. Lichtenstein also mimicked the Benday dots used in commercial printing, a process invented by American Benjamin Day around 1878 to replace black-and-white wood engraving with gradations of color. As in Turkey, Lichtenstein often employed the dots to simplify color schemes and emulate cheap newsprint. Devoid of detail, the turkey here looks banal, impersonal, and mechanically reproduced. The flatness of the painting challenges the relationship of representation to reality and deflates the Thanksgiving turkey as a national symbol.

This precisely arranged composition shows strawberries soon to be eaten with sugar and cream, hazelnuts and almonds, late-season grapes becoming raisins, and an orange. Influenced by seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes, Raphaelle Peale featured imported material goods in this painting, specifically Chinese porcelain made for the American market. In addition, his anticipation of the pleasures of eating (despite the lack of utensils), use of a simple ledge, darkened background, and raking light are borrowed from Spanish Baroque traditions. The large glass urn holding strawberries possibly alludes to experiments at Belfield, the farm where Peale’s father Charles Willson Peale “forced” fruit to grow out of season by using heated greenhouses called hothouses. Such horticultural activities enabled the composition’s nuts and fruits—which, in nature, mature at different seasons—to come together here as one dessert.

Beginning in 1888, the Philadelphia painter William J. McCloskey worked on a series of still lifes depicting oranges in various states—from wrapped and newly purchased to peeled and ready to eat. Arranging six oranges on a reflective tabletop, set against a complementary blue backdrop, McCloskey presents here an evocative study of form, texture, and color in a style of heightened realism. The artist excelled at depicting the crinkles and folds of the white paper as well as its semitransparency. The use of tissue paper to preserve oranges during transit was a recent innovation and, in combination with the perfection of the refrigerated railroad car in 1881, enabled fresh produce to travel great distances at lower costs. McCloskey’s painting celebrates the fruit’s formal properties and also documents the increasingly complex logistics that transformed orcharding and farming into large-scale industries.

In Vegetable Dinner, Peter Blume depicted two women at a table separated by a small pile of vegetables. The two figures—one watching idly with a lit cigarette as the other peels potatoes—suggest an opposition between the modern girl and the traditional worker, antithetical views of gender roles expressed through their associations with food. Blume later recollected that both figures were modeled by his then-girlfriend, and the painting has been interpreted as capturing Blume’s anxiety about committing to their relationship. The vegetables thus imply symbolic substitutes of male and female. But they also reference vegetarianism, a major subculture of American cuisine that often held religious, political, or ethical overtones. Blume became a vegetarian in the 1910s as a means of asserting his progressive beliefs, a choice that harmonized well with his modernist approach to painting.

- Gerald Murphy (1888–1964)

Cocktail, 1927

Oil on canvas, 291⁄16 x 29⅞ in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York;

purchase, with funds from Evelyn and Leonard A. Lauder, Thomas H. Lee, and the Modern Painting and Sculpture Committee

Art © Estate of Honoria Murphy Donnelly/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Gerald and Sara Murphy were wealthy Americans who lived in France during the 1920s. Their circle of friends included writers and artists, among them Constantin Brâncusi, James Joyce, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, and Man Ray. This painting shows Murphy’s sophisticated understanding of the influential European artistic movements of the period, especially the layering and patterning of Synthetic Cubism as well as the rigid geometry of a related style known as Purism. Seemingly mundane objects—the cocktail shaker, corkscrew, cut lime, and cocktail glass—are rendered in large scale and point to the activities of the bartender. Imported Cuban cigars are prominent, reflecting the popularity of smoking. The festivity suggested by the painting matched the carefree, spirited lifestyle of the young couple.

For Marsden Hartley, the symbolism of food extended to the process of mourning. In the mid-1930s Hartley briefly lived with the Masons, a devoutly religious family of fishermen in Nova Scotia. He was deeply affected when, in September 1936, the two Mason sons and a cousin drowned in a storm. Hartley mourned them through several paintings of the family, including Fishermen’s Last Supper, Nova Scotia. Numerous references to Christianity position this painting within a framework of religious sacrifice, most notably in the title and iconography, which refer to Christ’s Last Supper before his crucifixion, here suggested as meager and bleak. Hartley also explored similar themes in his poem “Fishermen’s Last Supper,” which begins, “For wine, they drank the ocean— / for bread, they ate their own despairs.” Hartley thus associated wine and bread with drowning and sorrow, and he memorialized his grief through the simple yet fraught act of sitting down to dinner.

Wayne Thiebaud began portraying cakes, desserts, sandwiches, and other food in the 1960s. The assortment in Salads, Sandwiches and Desserts is practical and almost utilitarian. The display points to the twentieth-century American culture of convenient foods, presented here by the many choices arrayed at a cafeteria or luncheon counter. Despite this emphasis, however, his paintings point to the significance of the personal touch in both American art and cuisine. Thiebaud dragged pigment onto the canvas with generous brushstrokes that lend a lush tactility to the different foods and highlight the play of light and shadow in these lavishly painted items. Thiebaud’s compositions are emphatically handmade and serve as a reminder that at this time, a new generation of chefs had begun to turn away from processed foods in a renewed focus on the art of cooking.

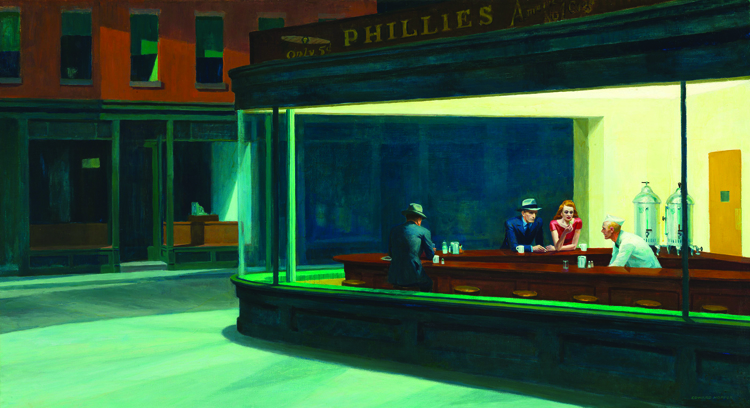

Hopper began Nighthawks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor caused New York City to institute blackouts. Walking the city’s darkened streets, he envisioned a brightly lit diner and the people therein. Tellingly, no food is visible — no posted menu, no display cases full of sweets, cakes, and pies. Hopper edited out the diner’s traditional enticements, seeking the intense realism that is the hallmark of his work. Instead, the focus is on the enigmatic relationship between the three customers. With keen observation, Hopper detailed the occasionally strained nature of urban dining, as patrons share a space without any sense of togetherness. Historically, diners were principally locales for working-class men; female patrons remained a rarity until World War II. Drawing on popular imagery from hardboiled fiction and film noir, Hopper explored the thrill of impropriety elicited by the sight of a modern woman, out late at night, meeting a man for coffee in an anonymous public space.

The exhibition opens with depictions of Thanksgiving, long recognized as the most important American holiday for uniting food, family, and ideas of prosperity with our national history and culture. The story of American art and food culture then begins in the Colonial era, where contrasts are made between paintings of sophisticated Bostonians and the rowdier behavioir of traders in the West Indies. These images set the stage for an examination of art in Philadelphia, where the birth of the natural sciences entwined with the lives of America’s first renowned still-life painter, Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825), and his extraordinarily artistic extended family.

By the 1840s, farm life increasingly gave way to urban dwelling, and food and its rituals drew sharp distinctions between country and city. For artists, the tension between nostalgia for simpler times and a growing middle-class prosperity appeared in food-laden scenes of everyday life. The years following the Civil War brought dramatic economic and social changes related especially to industrialization. Unprecedented wealth and materialism coexisted with acute poverty, and artists captured such differences in simpler compositions with a focus on lighting and paint application to convey a meal’s atmospheric setting or comment on race, class, and politics.

At the turn of the twentieth century, new ways of eating and socializing appeared in paintings that reflected changing artistic interests. As dinner moved to the evening hours, breakfast became less formal, restaurants flourished, and Prohibition complicated America’s relationship with alcohol, many artists embraced the new directions of modernism, which rejected illusionism in favor of using food subjects for aesthetic experiments. Still-life painting was an ideal vehicle for avant-garde exploration due to its lack of overt narrative and mundane subject matter—a perfectly apt description of Gerald Murphy’s Cocktail of 1927.

Tom Wesselmann positioned Still Life No. 15 as an all-American image by employing overt symbols of national identity, such as the Stars and Stripes and a reproduction of Gilbert Stuart’s iconic portrait of George Washington, against an image of a bucolic family farm. These icons of Americana are juxtaposed with a juicy, grilled steak and a bottle of Four Roses whiskey. The plate of beef alludes to the popularity of meat in the American diet. By 1960, Americans consumed an average of eighty-five pounds of beef annually. It also evokes the rise of a suburban culture in the postwar era focused around the backyard grill. Still Life No. 15 was the first of Wesselmann’s works to incorporate mammoth images originally intended for roadside billboards. The considerable scale heroicizes the mundane, affirming the significance of commercialism in American society.

In 1964, art critic Calvin Tompkins detected something particularly American in the popularity of food subjects among contemporary artists: “Supermarket food is so American. The great production belt of our largest industry overwhelms us at every season of the year with gorgeously colored, bigger-than-life-size comestibles, and if the frozen-in flavor of wax beans sometimes turns out to be the flavor of wax, this is all part of the world’s highest standard of living.” Photo-realist Richard Estes explored the mesmerizing world of the supermarket in Food City, showcasing the window displays of packaged foods and massive lettering of weekly sale ads intended to entice shoppers. Through the plate glass windows we see the consumers who propelled the increased consumption of supermarket goods in the 1960s.

With the birth of Pop Art in the 1960s, food offered artists the perfect subject for tapping into the ethos of mass consumption, convenience, and the power of advertising that dominated American culture. Artists, perhaps none as effectively as Andy Warhol, as seen in his acrylic Campbell’s Soup of 1965, appropriated familiar food products to rethink the role of food in art, challenging everything from Abstract Expressionism to consumer culture.

Art and Appetite: American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine is on view from February 22 through May 18, 2014 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. The exhibition was organized by the Art Institute of Chicago (where it is on view through January 27, 2014) and curated by Judith Barter, Field-McCormick Chair of American Art, who provided the caption text. The Fort Worth presentation is supported in part by generous contributions from Central Market, the Fort Worth Promotion and Development Fund, and the Ben E. Keith Foundation. For information call 817.738.1933 or visit www.cartermuseum.org.

Margaret C. Conrads is deputy director of art and research, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas.

This article was originally published in the 14th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.