American Sunset Paintings 1850 to 1900

To the nineteenth-century imagination, sunsets symbolized more than a simple transition from night to day. Sunsets mirrored a dramatic finale when, as Longfellow writes in Night, “the crowd, the clamor, the pursuit, the flight, the unprofitable splendor” of day melts “into the darkness and the hush of night” where “the ideal hidden beneath revives.” American landscapists of the late-nineteenth century portrayed twilight subjects with the same poetic fervor that is echoed in Longfellow’s words. Their rich, fiery palettes and luminous emanations form a powerful group of landscape paintings.

The trend of depicting evocative sunsets arose in the late 1850s when warmer and brighter pigments became available to artists. As E. P. Richardson, one of the pioneering American art scholars, records, “After 1856, a series of sharp new reds and purples flared upon the artist’s palette. Mauve was quickly followed by magenta and cobalt violet (1859) and cobalt yellow (about 1861).”1 Hudson River School artists Frederic Church (1826–1900), Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1880), and Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904) soon began making use of the new pigments in their mesmerizing canvases of blazing twilights. Church’s Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860 (The Cleveland Museum of Art), was a seminal sunset scene and doubtlessly inspired fellow landscapists to work in this genre.

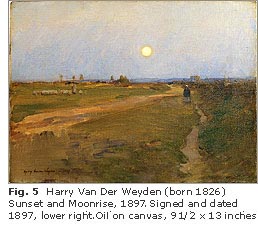

However, even before Twilight, A Sketch (the study for Twilight in the Wilderness) was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1859,2 George Inness (1825–1894) executed A Winter Evening in 1858 (Fig. 1). Michael Quick, a leading scholar on Inness, related in 1999 that this picture is the earliest known snow scene by the artist, as well as one of the few located sunset scenes by Inness dating from the period 1857–1858.3 Of the few early snow scenes painted by the artist, the majority are sunsets such as Winter, Close of Day (The Cleveland Museum of Art) and Christmas Eve (Montclair Art Museum), both executed in 1866. Iness appears to have delighted in the contrast between the white solemnity of snow and the vivid, burning colors of the sunset.

Inness later related in a letter to his wife how he experienced sunsets: “I have just been out to see the setting of the sun, strolling up the road and studying the solemn tones of the passing daylight. There is something peculiarly impressive in the effects of the far-reaching distance…and the general sense of solitariness which quite suits my present mood.”4 Inness’s perception of natural scenery filtered through his emotions and, correspondingly, his sunset scenes carry a thoughtful, slightly wistful timbre.

While Inness expressed mood in his sunsets, Sanford Gifford delighted in the pure visual spectacle of a sunset. During the mid-1860s, Gifford profoundly influenced his friend and contemporary T. Worthington Whittredge (1820–1910), whose style then shifted from a literal transcription of nature (a naturalistic approach he learned while training in Dusseldorf) to embrace a more poetic sensibility of form, atmosphere, and light.5 Twilight Landscape relates to similar twilight scenes that Whittredge painted in 1866 of Hunter Mountain, which is a possible site for this painting (Fig. 2).6

The nineteenth-century art historian Henry Tuckerman noted Whittredge’s new expressive use of color when he said, “There is sometimes not only a feeling for beauty in his color, which betokens no uncommon intimacy with the picturesque and poetical side of nature.”7 Although Tuckerman refers to a different landscape of this period, his description is also relevant to Twilight Landscape. Light plays a strikingly evocative role in this painting. A rich palette of red and orange pigments sets the turquoise sky ablaze in a fiery twilight. The brilliant colors of the horizon then reflect upon the glowing surface of the pond in the foreground and highlight the surrounding foliage. The juxtaposition of the mysterious twilight atmosphere with Gothic architecture reveals the Romantic ethos that Whittredge and other artists associated with sundown.

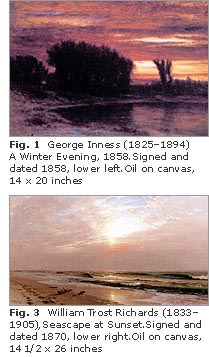

As a young man, William Trost Richards (1833–1905), the renowned late-nineteenth-century seascapist, displayed a similar romantic sensibility rooted in a “Wordsworthian reverence toward nature.”8 In a letter to a friend, the artist described a “desire that will not rest satisfied till landscape can tell stories to the noble heart and be a medium of powerful expression even as the human countenance.”9 Richards’s sunset scenes are visual testimonies to the artist’s success in creating emotionally telling and arresting images of nature. In Seascape at Sunset, 1870 (Fig. 3), the setting sun carries a spiritual, almost otherworldly resonance.

The idea of the sky as a spiritually potent realm figured prominently in the ideologies of the early nineteenth century. Carl Gustav Carus (1789–1869), the Dresden painter who wrote the compilation Nine Letters on Landscape Painting, referred to the sky as “the real image of the infinite…the most essential and most glorious part of the whole landscape.”10 By applying Carus’s methodology, the rays of sunlight in Richards’s sunset stream from the waning sun onto the ocean and shore, and can thus be interpreted, however symbolically, as visual bridges that bind the viewer with “the infinite,” the celestial zone of his creator.

If Inness captures the wistful sunset, Whittredge, the Romantic twilight, and Richards, the spiritualized sunset, then Henry Ferguson (1842–1911) portrays the exotic sunset in his painting, Egypt (Fig. 4). Ferguson worked as a landscape painter during the latter decades of the nineteenth century and traveled extensively throughout South America, Europe, the Mediterranean, and Egypt, the locale of this scintillating twilight. Throughout the nineteenth century, Egypt’s terrain served as inspirational subject matter for several prominent landscapists, including Frederic Edwin Church. In one of his eloquent travel journal notations, Church wrote that he “never saw so picturesque a scene as these Arabs…and the camels lying close by…[that] their huge forms looked still huger in the vague light.”11 Ferguson similarly evokes a colorful pageant of Bedouins and camels ensconced in dramatic light. The Orientalist appeal of the desert, its exotic climate, and the rich display of smoldering colors it exudes at sunset were vitally motivating factors in Ferguson’s creation of this canvas.

The last sunset we will consider, Sunset and Moonrise, 1897, by Harry Van der Weyden departs from the aforementioned twilights in its lack of brilliant, flaming colors and its cool palette and serene atmosphere (Fig. 5). Born in Boston in 1868, Van der Weyden expatriated to England in 1887 and then studied at the Academie Julian in Paris (with noted Academic artists J. P. Laurens and Benjamin Constant) during the 1890s. He soon fell under the spell of the quiet, pastoral charm of the French countryside. In Sunset and Moonrise a female peasant is depicted leaving the fields at the close of the day. The artist evokes a noble harmony that exists between his subject and the cycles of nature. As the sun departs, so does the peasant from her agrarian travail. Here, sunset serves as a foil for the hallowed idyll that Van der Weyden, other impressionists, and the Barbizon painters before them associated with the French provinces and their inhabitants.

Henry David Thoreau recognized the theatrical nature of sunsets when he wrote: We never tire of the drama of sunset. I go forth each afternoon and look into the west a quarter of an hour before sunset, with fresh curiosity, to see what new picture will be painted there, what new panorama exhibited, what new dissolving views. Can Washington Street or Broadway show anything as good? Every day a new picture is painted and framed, held up for half an hour, in such lights as the Great Artist chooses, and then withdrawn and the curtain falls.12

Essentially, the sky at sunset becomes for the “Great Artist” and for the literal artist a screen upon which man’s inner dramas—the calm and fury, the pride and pathos, and the sorrow and hope of our existence—are brilliantly played out.

Jennifer Krieger is the director of Questroyal Fine Art, LLC.

All illustrations courtesy of Questroyal Fine Art, LLC.

Cited in John Wilmerding, American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850–1875 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), p. 16.

Michael Quick and Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., George Inness (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1985), p. 90.

Telephone conversation with Michael Quick, October 26, 1999.

George Inness, Jr., Life, Art and Letters of George Inness (New York: The Century Co., 1917), p. 163

Whittredge and Gifford initially became friends during their stay in Rome with Albert Bierstadt between 1856–1857. Anthony Janson, Worthington Whittredge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 91.

Conversation with Anthony Janson, August 1, 2000.

Cited in Janson, p. 90–91.

Linda S. Ferber, William Trost Richards, American Landscape and Marine Painter (Brooklyn: The Brooklyn Museum, 1973), p. 32.

Cited in Ferber, p. 15.

Cited in Barbara Novak, Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 1825–1875 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 82.

Church’s Petra diary, 27–28, Olana Archives, cited in Eleanor Jones Harvey, The Painted Sketch: American Impressions from Nature, 1830–1880 (Dallas Museum of Art, 1998), p. 184.

Henry David Thoreau cited in Novak, p. 78.

.jpg)

.jpg)