French Island Elegance

Much has been written about the French West Indian islands; about their botany, zoology, and their social and economic histories, but to date, little or no consideration has been given to the architecture and decorative furnishings of the islands discovered by Christopher Columbus in the late fifteenth century and colonized by the French in the seventeenth century. Since French culture and fashion dominated European taste from the Renaissance well into the nineteenth century, an examination of the unique French West Indian decorative arts is overdue. The subject, however, presents several challenges. To begin with, there is little documentation of furniture origin; the climate has taken its toll on French island furniture, as did the nineteenth-century slave rebellions, when entire plantations were burned to the ground. Yet despite the depredations of time and history, hundreds of pieces of furniture still remain in private collections on the islands, and growing conservation awareness is contributing to the restoration of significant buildings. Case in point; when the Bernard Hayot Group acquired L’Habitation Clement in 1986 as part of their purchase of a century-old rum distillery, they decided to restore this eighteenth-century example of the art of building on Martinique. It is now the first French islands house open to the general public.

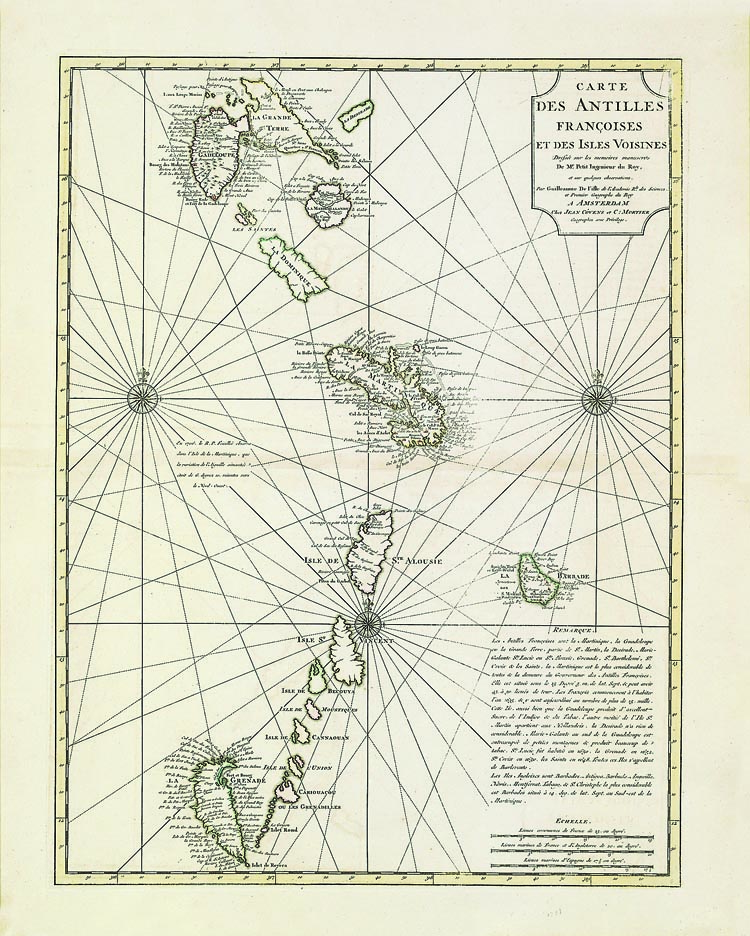

Discovered by Columbus on his second voyage to the New World in 1493, he named the islands Las Indias Occidentales, the West Indies, thinking he had arrived at the Indies, the archipelago off the coast of Asia. Since the islands contained no gold and the indigenous Carib inhabitants proved warlike and troublesome, Spain had little interest in colonizing them. France’s successful conquest of the islands began in the seventeenth century as a result of the French government’s new colonization policy. They made their first claim on the island of Saint Christopher (now Saint Kitts). In the 1630s French expeditions resulted in the colonization of Guadeloupe and Martinique. By 1636 they had possession of Saint Bartholomew and Saint Martin, which they later shared with the Dutch. In 1650, Grenada fell to the French and they laid claim to Saint Lucia. In the same year they took possession of Saint Croix. By the 1680s they had secured a portion of Guiana and the island of Tobago. And by the close of the century Spain confirmed France’s claim to Saint Dominque, as Haiti was called until its independence in 1804.

Many of the early French settlers were of noble birth and as encouragement had their passage paid for by the Compagnie des Isles d’Amérique, established to administer the French colonies. The company also offered aid to tradesmen such as carpenters and woodworkers needed in the new settlements; they had only to bring their tools. But most abandoned their craft once they discovered the financial advantages of working with sugarcane and coffee. These two commodities were European staples and it was the cultivation of sugarcane in particular, for which the islands’ climate was perfect, that made the colonists rich and enabled them to live in the grand manner. To be si riche comme un Créole (as rich as a West Indian) was a popular phrase in Paris during the height of the colonial period in the eighteenth century. The use of slave labor contributed to the sugarcane planters’ huge profits. By the end of the eighteenth century, Africans outnumbered Europeans on all the French islands.

- Typical of the early French colonial great houses, Habitation Pécoul on Martinique, built in 1760, features large doors that align with those in the front, allowing for air flow and cooling tropical breezes to pass through the main floor. Bedrooms are located on the second floor. Shown here is the rear of the house.

Three factors influenced colonial architecture: the inhospitable climate, the plentiful supply of hardwoods, and colonists desire to emulate the French tradition in architecture and lifestyle. The varied French island styles that exist in the islands today emerged over the course of the seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries and were developed further throughout the remainder of the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century. More than any other European colonists the French islands’ colonists succeeded in marrying the forms and styles of the mother country to the climate and materials of the islands.

The French colonists, determined to live as opulently as possible in their island homes, made their plantation homes the symbol of their wealth and standing. Their large habitations typically included the maison de maître (“great house”), the out buildings, the sugar mill, the refinery, the stables, and the slave quarters (rue cases-nègres). The great houses were almost always situated on knolls or hills to take advantage of tropical trade winds, and had large rooms with high ceilings. The ground floor rooms typically had a series of double “French doors,” with louvered shutters and cove ceilings, known on the islands as “tray ceilings” because of their resemblance to inverted tea trays. Seldom were glass windows or doors used.

Early colonists imported their furniture from home, but the European softwoods quickly succumbed to the ravages of the tropical elements and insects. This created opportunities for local craftsmen to make replacements. Using the imported furniture as models, the island cabinetmakers gave them their own interpretations and embellished them with their own decorative motifs, in the process creating a unique French colonial furniture style.

There is little written documentation about interior furnishings of the colonial years. Since cabinetmakers did not label, brand, or date their pieces, their only legacy is their small body of remaining furniture. It is clear that the majority of the colonial island cabinetmakers were of Africa heritage; either slaves or their descendants (gens de couleur, free colored). Obtained from Africa’s Gold Coast and from Whydah on the Slave Coast, the slaves brought with them their exceptional skills in basket weaving, thatching, pottery, and woodwork. On the French islands, local furniture soon became an amalgamation of different styles: French; the “down island” furniture made on other islands; and the local craftsmens’ intuitive sense of design and use of African decorative imagery. Mahogany, so plentiful on the islands, was the furniture maker’s wood of choice, with locust and courbaril also being used. Particularly in the nineteenth century, French West Indian furniture represents a vernacular style, distinguished by a variety of traditional African motifs, which include zoomorphic forms. These motifs are a definitive source of identity for island furniture.

In the late eighteenth century, French West Indies furniture followed simple neoclassical lines. By the turn of the nineteenth century, neoclassical furniture was being relegated to the slave quarters to make way for the newer taste in Empire style, which predominated until the twentieth century, and accounts for much of the furniture still in evidence from the past. Although it is usually impossible to know if a particular piece of furniture was created by a local craftsman, an itinerant French island craftsman, or by an artisan from another European colonial island who had seen or been commissioned to copy a French piece, there is overwhelming evidence to support the theory that woodworkers and cabinetmakers from the French islands traveled from island to island, spreading their own interpretations of European designs.

One furniture form that survives in quantity is the four-post bedstead. The French island bedsteads are distinguished by their large size (mostly due to the inexhaustible supply of tropical timber), tall posts with intricate turning and/or carving, solid headboards, often with foliate carvings, and the overall height of the bedrails. The most distinguishing feature of French West Indian beds during the colonial period are the posts. Without exception, all four posts were turned and carved from the same type of wood, usually mahogany or courbaril. The headboards on these beds are usually solid, tall, plain boards or a series of boards. The bedrails are always high above the ground to facilitate air flow, so that the mattress is at the level of the windows, and, therefore, in a position to take advantage of the tropical breezes.

Another popular furniture form was the French island méridienne, often referred to as fauteuil récamier. The name, récamier, is derived from the painting by French artist Jacques Louis David of Madame Récamier, which portrays her reclining on this type of couch. It is one of the few French West Indian seating furniture forms that was sometimes found upholstered in a traditional manner. Called a “Grecian couch” in contemporary descriptions, the design was based on Greek and Roman models. The earliest examples of upholstery made in the islands were cushions, mattresses, or pillows, stuffed with either coconut husk, cotton, feathers, or a combination of these materials. The tropical heat, humidity, and insects, combined with the inability of upholstered pieces to “breathe,” caused them to decay quickly. What might have been considered a fashionable piece was soon unpopular for practical reasons, and French island craftsmen quickly returned to the use of more efficient caned furniture. Most of the French island méridiennes were crafted of mahogany or courbaril; they were hand caned and were typically made in pairs: a right- and a left-hand couch.

By the late 1850s the era of sugar prosperity was over and the abolition of slavery led to smaller island homes and less elaborate furniture. On Martinique the twentieth century was ushered in with the eruption of Mount Pelée, which killed thirty thousand people and destroyed the city of Saint Pierre, the center of culture and wealth for the French islands.

The gradual exodus of the plantocracy hastened the decline in cabinetmaking until the few shops remaining survived on repair work and caning, requiring little skill. Although the French island furniture making tradition may have disappeared, in the past ten years interest in the unique French island forms has been on the rise. The work of the colonial furniture craftsman remains a tribute to their versatility, skill, and genius for innovative design and execution.

Bruce Buck is a highly regarded photographer of interiors, architecture, and the decorative arts.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. Antiques & Fine Art is affiliated with InCollect.com.