Ideas from the Field

America’s Historical Illiteracy and the Future of Art & Antiques.

At Drayton Hall, a historic site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation in Charleston, South Carolina, a museum interpreter, about sixty-five years old, welcomed a group of elementary school students to the site. She summarized the history of the plantation and explained that construction of its main house had begun in 1738. When she paused for questions, a student politely raised her hand and asked, “Were you living here when the house was built?” Another story comes from the manager of the museum’s shop where Civil War caps from both armies are sold. About twice a month, adults ask the manager, “What’s the difference between the blue cap and the gray?” Such stories are told across the nation, but are not relegated to historic sites. Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough tells of giving a lecture at a well-respected college in the Midwest. Afterwards, a bright student told him, “Until I heard your talk, I’d never realized the original thirteen colonies were all along the East Coast.” 1

While we may chuckle or shake our heads, these stories illustrate what McCullough and others have characterized as “America’s historical illiteracy.” It is hard to imagine what time frames and maps many people carry in their heads. When they hear “Federal style” or “Greek Revival,” what must come to mind? What about “Hudson River School of painting,” especially if there is no river? Should we in the world of antiques and fine arts care? Let’s consider what’s at stake: Can a dealer hope to sell objects when customers have little understanding of different periods of time or appreciation of history? Lovers of decorative arts know that people can simply have an appreciation for beautiful objects (Fig. 1). One need not know what Georgian means in order to appreciate the beauty of the design and artistry of carved mantles or decorative ceilings in Drayton Hall (Fig. 2). There are certainly young people acquiring material, but much of this is in the form of accent pieces or contemporary art and objects. While any manner of collecting should be encouraged, what will augment interest in collecting historic works? The answer is an understanding of history, which puts antiques and fine art in context and deepens and enriches the way they are appreciated.

According to noted antiques dealer and cultural historian Sumpter Priddy of Alexandria, Virginia, “Objects are irrelevant unless we have the capacity to understand them. We need to know how they fit into our history and illuminate who we are—and also how to categorize them so we can retrieve their gifts when needed.” Priddy comments, “Ideally, I aspire to find and interpret old things that teach us something we haven’t previously understood about our culture.” 2

In a recent article in the News & Observer, William H. Pruden III, head of the Upper School at Ravenscroft School in Raleigh, North Carolina, noted: “Today, in a country seeking to regain its economic and political footing, educators, business leaders, politicians, and concerned citizens are asking hard questions about the very nature of education and about the skills and knowledge needed by twenty-first century learners. And yet no academic area is viewed with more skepticism than history…The best educational experience is the sum of its parts, but arguably it is history that ties it all together, providing context and connections across generations and genres. It provides the foundation for individual, institutional, and cultural understanding.”

According to Common Core, a national educational organization, a recent survey of 17 year olds reveals that half the students did not know what the Renaissance was, and the 2010 National Assessment of Educational Progress found that only 12% of high-school seniors have a firm grasp of our nation’s history. Half did not know in which century the American Civil War took place.3

What are the causes for such illiteracy? For over half a century, schools have focused on other subjects beside social studies—most recently on the STEM subjects of science, technology, engineering, and math. No one would argue that math and science are not important components of a comprehensive education, especially in today’s global economy, but where are the forceful arguments for art, culture, and history? The federal government’s No Child Left Behind legislation has exacerbated the problem with its required end-of-year assessments in English and math to measure performance. If history, social studies, and art are not tested, those subjects lose out. According to Common Core, most teachers surveyed report that schools are narrowing the curriculum by shifting instructional time and resources toward math and language arts and away from art, music, foreign languages, and social studies. In addition, recent educational trends have given more weight to skills than to content, i.e., the narrative of what happened when, how, where, and why.4 Rather than being quick to blame the teachers and students, we need to take a closer look at the educational policies and practices that our nation has adopted.

Community Partnerships:

Suggestions for How to Make a Difference

“Antiques Detective” Benefits for Local Schools: Inspired by Antiques Roadshow,* and in alliance with the local schools, invite children and their families to bring in objects from their homes for evaluation and possible appraisal. The children will gain new appreciation for something that might previously have been taken for granted. Students can be encouraged to write about the object, or draw or paint it. Proceeds from the benefit can fund field trips to art and history museums or other programs to advance the study and appreciation of art and antiques.

Gallery to Classroom: Partner with teachers to use art, antique reproductions, and material culture in the classroom. Such a program has the potential to educate teachers as well as their students, and could form part of their professional development requirements.

The Simple Power of “Thank You”: Invite teachers, curriculum coordinators, principals, and school board members to art exhibit openings, antique shows, private receptions, and other events to create and nurture networking opportunities. Educators are rarely invited to such events, and this is a way to acknowledge them and say “thank you” for their hard work and dedication.

* Antiques Roadshow is a trademark of the BBC and is produced for PBS by WGBH under license from BBC Worldwide.

Fritz Fischer, professor of history and history education at the University of Northern Colorado and former chairman of the National Council for History Education, has this to say about the shift in emphasis in our education system: “My worry is that as challenging, thought-provoking history disappears from the national schools, both the habits of mind and the appreciation for the beautiful items from the past will disappear from our otherwise present-oriented society.” 5

To redress this state of affairs, the art and antiques community must support—publicly and financially—the best approaches for history education. We must engage our children in the content and excitement of history—in the story—both in the classroom and at home. To be successful, those in fine art and antiques must get involved, seek alliances with organizations devoted to history and historic preservation, and help shape the best way to incorporate decorative arts, fine art, and material culture into the teaching of diverse disciplines, not just history. Organized efforts to positively influence curriculum and assessment have been successful. South Carolina teachers successfully lobbied to keep social studies as a part of the end-of-year assessment, despite seven attempts by the state legislature in the past decade to remove it.

Too often in the past, the teaching of history has narrowly focused on politics, economics, and wars. But that is changing, and needs to change even more. Organizations like the American Alliance of Museums, the National Council on History Education, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, as well as the activities of state and local arts and history organizations, constitute an excellent start for alliance-building with schools. Programs across the country linking museums with schools are accenting the teaching of history and integrating art and material culture into it (Figs. 3, 3a). Too often, however, such programs are underfunded or are undercut by the emphasis on other subjects. Supporting your local art or history museum or school can go a long way in making such programs accessible. One example is at Drayton Hall, where history programs follow this approach, integrating, say, the Revolutionary War with art, material culture, and interactive activities. Fortunately, in some cases, donors have adopted classrooms, so that despite budget cuts to the schools, the students have been able to afford the field trips and pay for the school buses.

At Drayton Hall, approximately 10,000 students and teachers pass through our gates every year to learn about the history of the site and the people who lived here. These numbers would certainly dwindle without a never-ending campaign to update our programs and ensure enough donations and grant money so that schools with a high concentration of low-achieving students and students living in poverty can continue to come on field trips to Drayton Hall.

History is typically taught through the written or spoken word, but objects offer the opportunity to engage minds in a different way. As Dr. Estevan Rael-Gálvez, senior vice president for historic sites at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, expresses it: “The hundreds of thousands of collections objects held at our [National Trust] sites offer a deeper connection to the public—a tangible bridge, illuminating the past, informing the present, and inspiring a future.”

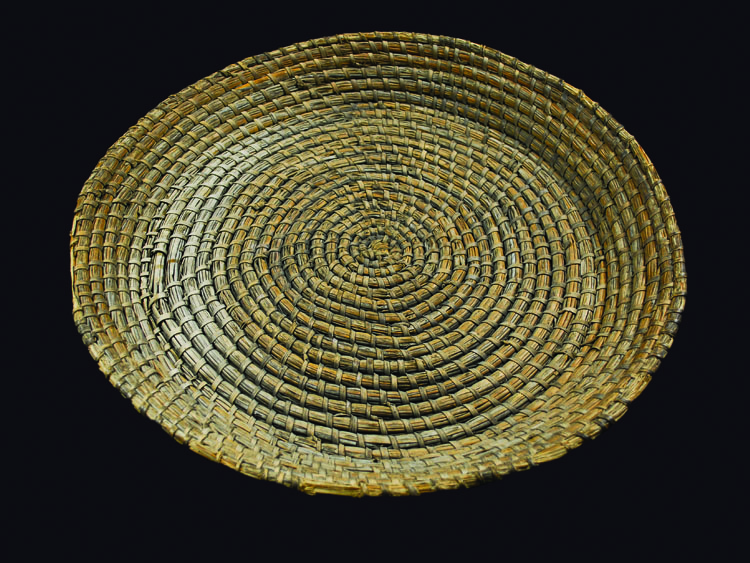

The challenge is to find ways to give expression to those connections. Drayton Hall offers examples. Using a range of items, from fanner baskets that illustrate the rice culture in the South Carolina Lowcountry (Figs. 4, 4a) to Chinese export porcelain and colonoware that illuminates the material culture of the Draytons and the enslaved people, respectively, Drayton Hall teaches through these historical objects with great success. Teachers report that they often expand on their on-site experience by using our post-visit activities. Students who are kinesthetic, visual, or auditory learners can translate what they have learned into a drawing or painting, or craft an object, or write a poem or play, or produce a dance or piece of music.

If history is inquiry, then objects offer a bridge to the past in ways that the written word cannot (Fig. 5). They raise questions: How was it made? By whom? When? Where? And why? Recently interviewed in the Wall Street Journal about the state of history education in our country, David McCullough remarked, “History is a source of strength—it sets higher standards for all of us. But helping to ensure that the next generation measures up will be a daunting task.” 6

If we wish to realize our positive vision for the future of art and antiques, then museums, dealers, collectors, and educators must work together more effectively in order to counter the prevailing negative trends in history education and help develop a stronger case for how the study of history is deeply enjoyable—and craft curriculum and teaching methods to make it so—and why it is critical for the future of both our field and our nation.

Drayton Hall, circa 1738, located about 12 miles up the Ashley River from Charleston, SC., is the oldest unrestored plantation house in America still open to the public, and the earliest fully executed Palladian structure in North America. In 1974, The National Trust for Historic Preservation acquired the site from the Drayton family after seven generations of ownership. Instead of restoring it to a specific time period, the Trust took the radical approach to “preserve,” or stabilize, the site and to show the house unfurnished since exhibiting furnishings would have required the addition of climate control systems. Together, all daily public tours, private connoisseur tours, student programs, adult group tours, website (www.draytonhall.org), and social media channels, including www.facebook.com/DraytonHall, seek to provide compelling stories of history and the importance of historic preservation. Drayton Hall’s significant collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century decorative arts and artifacts—available now only by way of behind-the-scenes tours—awaits conservation and exhibition in future facilities. In response to visitor requests “to see the stuff and learn more about the people,” Drayton Hall has recently installed photographic exhibits inside the house and elsewhere on site. These will change throughout the year and showcase selections of decorative arts and archaeological artifacts along with images of the landscape and people.

All images courtesy of and taken at Drayton Hall.

1. Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2011.

2. Email correspondence with author.

3. Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2011; U.S. History 2010, National Assessment for Educational Progress at Grades 4, 8, and 12, U.S. Department of Education, NCES 2011-468.

4. “Learning Less: Public School Teachers Describe a Narrowing Curriculum,” Common Core, March, 2012.

5. Email correspondence with author.

6. Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2011.