5 Serene Frank Lloyd Wright Houses Worth Slipping Away To This Summer

|

rank Lloyd Wright's impact on American architecture simply cannot be overstated. Over the course of a career spanning more than 70 years, Wright designed over 1,000 homes, offices, schools, and other structures across the United States (more than half of which were completed), not only spearheading a shift away from the pastiche of borrowed European styles that dominated American design at the time, but coming to define a movement (or two) of his own.

Above all else, Wright's designs promoted a philosophy that would come to be known as "organic architecture," a harmony between human habitation within the natural world. Whether tucked away in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania or adorning the limestone bluffs of Iowa, many of Wright's publicly-viewed houses make for the perfect tour destinations worth checking out this summer. As luck would have it, we've selected 5 such homes to get you started.

|

|

737 Frenchmans Road, Stanford, CA 94305

For more information call (650) 725-8352 or visit hannahousetours.stanford.edu

| ||

| Hanna House. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. | ||

| ||

Fountain at Hanna House. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

Both Wright’s first work in the San Francisco region and his first work with non-rectangular structures, The Hanna House (also known as the Hanna-Honeycomb House, for the design from which Wright drew inspiration) was designed as part of a 25-year collaboration with Stanford Professor Paul Hanna and his wife, Jean. Set upon a hexagonal floor pattern with a distinct lack of right angles — hence, the honeycomb reference — the building serves as one of the earliest examples of the open floor plan that Wright would eventually champion in many of his structures. In keeping with Wright’s “organic architecture” philosophy, the Hanna House actually completes the hillside on which it is set, and is constructed of native redwood boards and San Jose brick. After a lengthy restoration, completed in 1999 following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the house has been open to the public ever since, and will be reopened for tours starting in June.

|

|

6472 Old Lake Shore Road, Derby, New York

For more information call (716) 947-9217 or visit graycliffestate.org

| ||

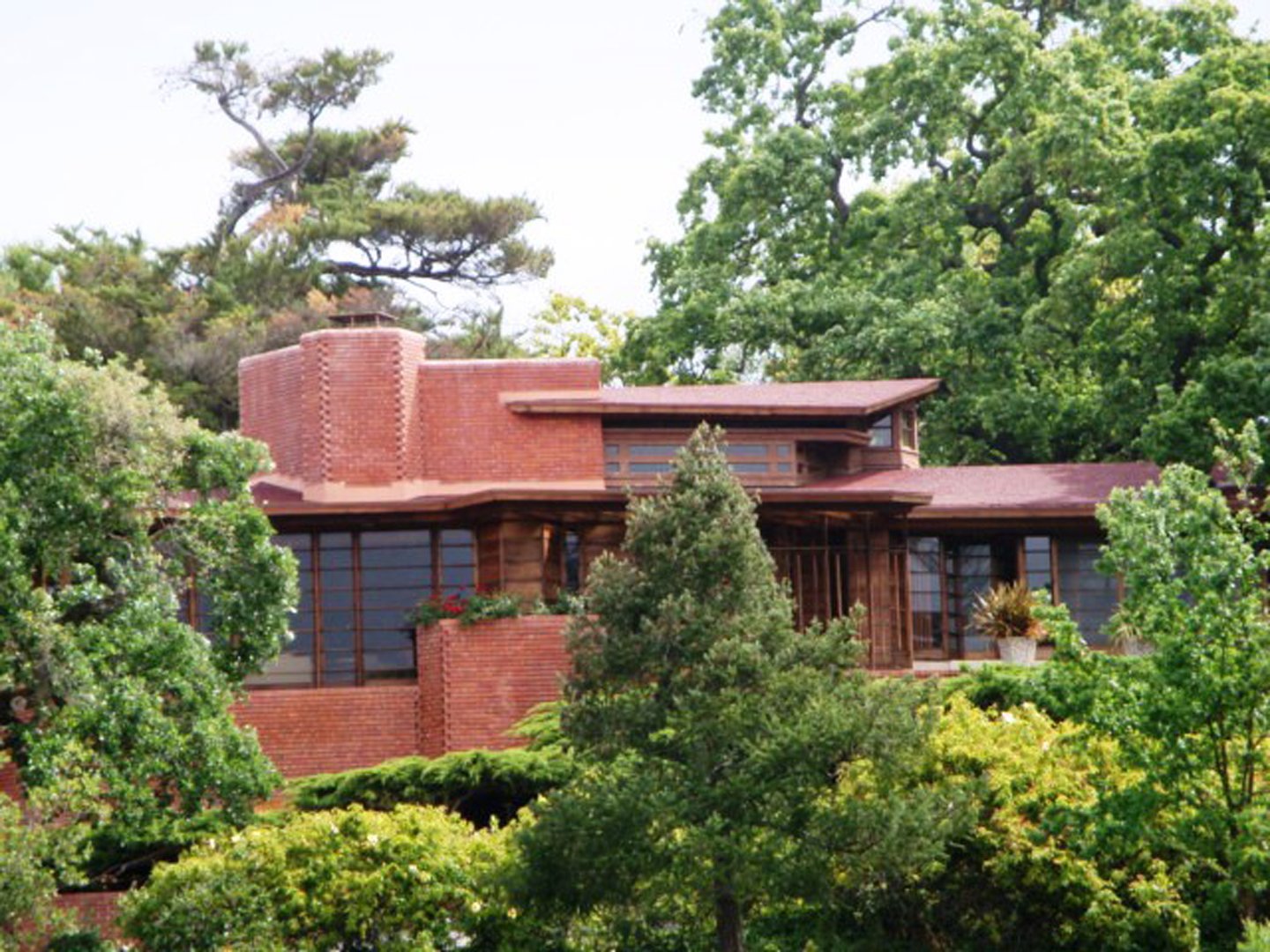

| Foster House at Graycliff. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

| ||

| View through Porte Cochere of Fountain at Graycliff. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

Perched atop a sweeping cliffside overlooking Lake Erie, Wright’s Graycliff estate is considered to be not only one of his more ambitious projects, but also one of the most important works of his mid-career “organic” style.

The three-building, 8.5 acre complex was designed as the summer home of Isabelle R. Martin and her husband, Buffalo entrepreneur Darwin D. Martin, both of whom grew to become close friends of Wright by the time the daunting establishment was finally completed in 1935 (having begun construction some 10 years earlier). The result of such a lengthy ordeal? A gorgeous stone and glass mecca of modern intuition featuring cantilevered balconies, expansive terraces, and a revolutionary pavilion-like center of transparent glass walls in its largest section, which allows visitors to see through the building itself and to the lake beyond. Surrounded by grounds and gardens personally designed by Wright, Graycliff has rightfully been dubbed by some as “The Jewel on the Lake.”

|

|

Buch Co Hwy W-35, Independence, IA 50644

For more information call (319) 934-3572 or visit iowadnr.gov/Places-to-Go/State-Parks

|

| Cedar Rock State Park. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

How important is Wright’s Cedar Rock residence, you ask? Oh, only important enough to receive its own state park designated to it. Constructed along the banks of the Wapsipinicon River near Quasqueton, Iowa, in 1950, Cedar Rock is one of the finest examples of Wright’s “Usonian” style, which would later influence the Ranch Houses we see in many American suburbs today.

Like many of Wright’s Usonian homes — which were designed not for his typically affluent clientele, but for distinctly middle class, everyday families — Cedar Rock’s plans were laid out on a grid to allow for greater standardization of the materials used to construct it (many of which were left unpainted to additionally reduce costs). What separates Cedar Rock from many of its Usonian counterparts, however, is the degree to which its interior bears Wright’s fingerprint: the furniture, the carpets, the draperies, and even the accessories were handpicked and designed by Wright and remain inside the house to this day.

|

|

869 W. Main Street, Silverton, Oregon

For more information call (503) 874-6006 or visit thegordonhouse.org

|

The Gordon House. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

As Wright’s career advanced, he began to incorporate glass into his designs in bigger and bigger ways, believing it to be the purist way for a home and its occupants to interact with the natural world that surrounded them; Wright often compared glass to the mirrors of nature: rivers, lakes, and ponds. Few of his Usonian masterpieces drove this philosophy home better than The Gordon House, a two-story with cedar and painted cinder block walls that give way to twelve foot, floor-to-ceiling windows and French doors that place the great outdoors just steps away.

|

|

1491 Mill Run Road, Mill Run, PA

For more information (724) 329-8501 call or visit www.fallingwater.org

|

| Fallingwater. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

Any discussion of Wright’s works, whether serene, inspiring or otherwise, would be incomplete without at least a mention of his most revered work, Fallingwater. Built over a thirty-foot waterfall in Bear Run, Pennsylvania, Fallingwater appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1938, was named as the “best all-time work of American architecture” by the American Institute of Architects, and is listed among Smithsonian’s Life List of 28 places “to visit before you die” (among other accolades).

The Japanese-influenced architecture of the building features many of Wright’s signature touches — cantilevered balconies, strong horizontal and vertical lines, and his signature Cherokee red paint on the steel — and though its construction was almost constantly bedeviled by conflicts between Wright and Edgar Kaufmann, the Pittsburgh businessman for whom the house was designed, it remains one of the most widely-visited homes in American history.

|

READ THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES ABOUT FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT FROM INCOLLECT

Top 11 Frank Lloyd Wright Houses You Can Tour

A Sneak Peak at MoMA’s Frank Lloyd Wright Retrospective

The U.S. Nominates 10 Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings For the UNESCO World Heritage List

Crystal Bridges Unveils Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bachman-Wilson House