N. C. Wyeth: New Perspectives

| |

Fig. 1: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), Self-portrait with Palette, ca. 1909–1912. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30⅛ inches. The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection. |

Newell Convers (N. C.) Wyeth (1882–1945), one of the foremost illustrators of his generation and the patriarch of an extraordinarily artistic family, is an often-overlooked figure in the history of American art. N. C. Wyeth: New Perspectives, at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, is the first sweeping view of Wyeth’s entire career in nearly fifty years. Through around seventy paintings and drawings selected from major museums and private collections, it offers a reintroduction to an artist many of us thought we knew. By repositioning Wyeth as a distinguished painter (Fig. 1) who worked across the perceived divisions of visual culture in painting, illustration, murals, and advertising, the exhibition offers new insights on Wyeth’s place within the spectrum of early twentieth-century visual arts.

In October 1902, twenty years old and deeply attached to his family and hometown of Needham, Massachusetts, Wyeth relocated to Wilmington, Delaware, to study with the preeminent illustrator and teacher Howard Pyle. Despite his Northeastern upbringing, Wyeth chose to specialize in depictions of the American West, his enthusiasm fired by the work of Western artists such as Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell, and Charles Schreyvogel. In 1904, Wyeth traveled in Colorado and New Mexico for almost three months; two years later he returned to Colorado for a brief stay. On the walls of his Wilmington studio hung all manner of cowboy gear and Native American artifacts that he had collected, props that would add a touch of authenticity to his Western imagery. He steadily mined popular themes of a bygone era—animated with cowpunchers (Fig. 2), desperadoes and Native Americans (Fig. 3)—to great fame and further commissions. He dealt in the dramatic, romantic imagery of the mythical “Old West,” rather than historically accurate renderings.

|  | |

| left: Fig. 2: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), Saturday Evening Post, cover (Bucking Bronco), 1903. Oil on canvas on hardboard, 27½ x 19½ inches. Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles. right: Fig. 3: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), In the Crystal Depths, 1906. Oil on canvas, 38 x 26 inches. Brandywine River Museum of Art. Museum purchase (1981). | ||

|  | |

| left: Fig. 4: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), The Scythers, 1907. Oil on canvas, 38 x 27 inches. The University of Arizona Museum of Art; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel L. Kingan (1952.001.085). right: Fig. 5: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), Tapping up and down the road in a frenzy, and groping and calling for his comrades, 1911. Oil on canvas, 47 x 38 inches. The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection. | ||

Despite his success as a Western artist, Wyeth realized his heart lay in the rural countryside around Chadds Ford, in Southeastern Pennsylvania. He had come to “the Ford” first in 1903, as a student in Howard Pyle’s summer school. Smitten with the gentle hills, pastureland and rich history of the Brandywine valley, in 1907, Wyeth and his wife Carolyn left the Wilmington art community and settled in a rented farmhouse in Chadds Ford. The natural beauty of the area sharpened the artist’s inclination for landscape painting, but it also underscored the tension between illustration and fine art that would trouble him for the rest of his life. In many of his paintings from this period he tried to bridge the perceived gap between these two aspects of his practice (Fig. 4), but he occasionally admitted, “the viewpoints of the painter and the illustrator are so entirely different.” 1 Wyeth found inspiration in the art and career of Winslow Homer, who had overcome the pejorative connotations of illustration to become the most famous American artist of his time.

In 1911, Wyeth was offered a commission that would define his artistic legacy for generations. Charles Scribner’s Sons hired him to illustrate a new edition of Treasure Island. He created images that profoundly enriched Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel, bringing to life unforgettable characters (Fig. 5), while exploring the universal melancholy of leaving home and the very human fear of the unknown. The illustrations were a popular success, securing Wyeth a new level of public recognition that led to similar commissions throughout the 1910s and 1920s.

|

Fig. 6: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), The Studio, ca. 1913–1915. Oil on canvas, 16 x 20¼ inches. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Frank E. Fowler. |

|

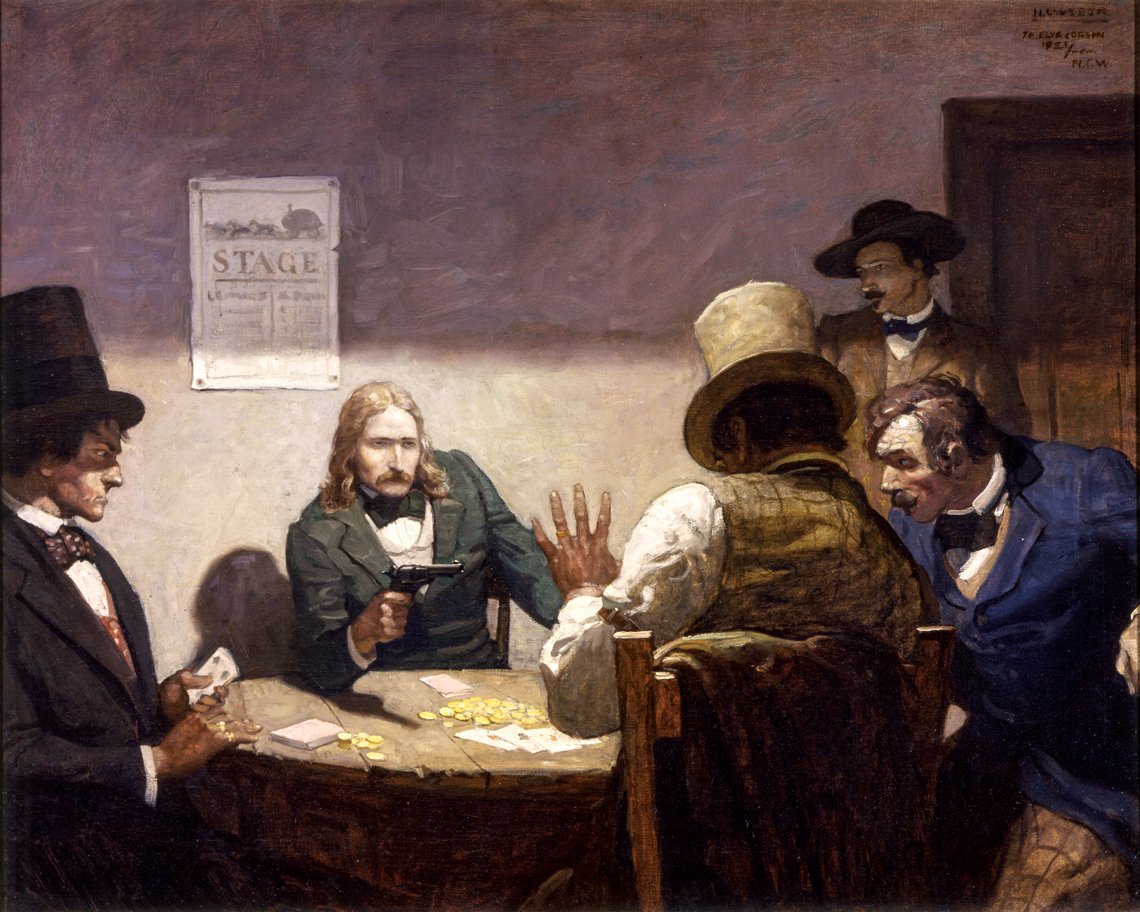

Fig. 7: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), The man with the hatful of cards picked a hand out of his reserves, put the hat on his head and raised Bill a hundred. Bill came back with a raise of two hundred, and as the other covered it he shoved a pistol into his face observing: “I’m calling the hand that is in your hat.” 1916. Oil on canvas, 32 x 40 inches. William I. Koch Collection. |

| |

Fig. 8: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), September Afternoon, 1916. Oil on canvas, 42 x 48 inches. Collection of Frank and Susan Jackson. |

With his earnings from Treasure Island, Wyeth purchased eighteen acres of land on a rocky slope just south of Chadds Ford village, where he built a house and studio (Fig. 6). The studio, erected on the hill above the house, offered a spectacular view of the surrounding countryside through its dramatic Palladian-style window. From here, the artist would cultivate a profound sense of place that would nourish his art and inspire the art of his children and grandson.

Despite the commissions that poured in, Wyeth continued to struggle to develop a personal artistic vision and at the same time support his family. The paintings from the period show the diversity this balancing act demanded of him—he produced a heady mix of paintings on subjects as far ranging as Arthurian knights to Wild Bill Hickok (Fig. 7), from a New England skipper to an aged Rip Van Winkle, as well as Chadds Ford landscapes of breathtaking beauty (Fig. 8).

| |

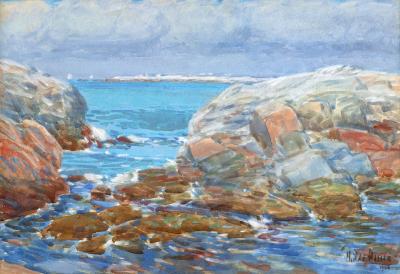

Fig. 9: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), The Harbor at Herring Gut, 1925. Oil on canvas, 43 x 48⅛ inches. The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection. |

In 1920, the artist purchased an old seaman’s house on a rocky shore in the small mid-coastal Maine fishing village of Port Clyde (Fig. 9), thus giving himself a foothold in New England for which he had long yearned. Wyeth drew fresh inspiration from this new setting, and his life and art would be profoundly enriched by his association with the coast. In 1925, Wyeth’s mother, Henriette Zirngiebel Wyeth, died. She had been the parent who had encouraged her son’s artistic talents, and the one to whom he had written hundreds of letters documenting the triumphs and failures of his life and career. At her death, he recommitted himself to personal painting, and in the ensuing two decades he explored themes of memory, family, and death. He experimented with the visual innovations of modernism, fractured and dreamlike imagery, vivid palettes, and imagined perspectives (Fig. 10).

|

Fig. 10: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), Ridge Church, 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 x 40⅛ inches. Collection of Linda L. Bean. |

|

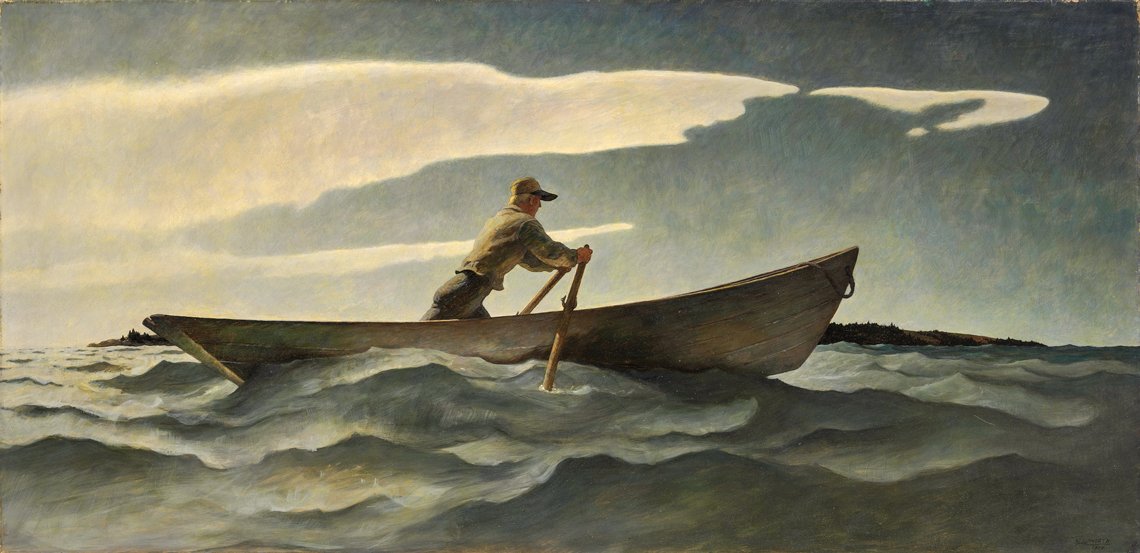

Fig. 11: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), Dark Harbor Fishermen, 1943. Tempera on hardboard (Renaissance Panel), 35 x 38 inches. Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. Bequest of Elizabeth B. Noyce (1996.38.63). |

In his late fifties, Wyeth turned to a new medium—tempera on panel—to create powerful images rooted in his Chadds Ford and Port Clyde experiences. He had arrived at a successful combination of the two main (and seemingly opposing) veins of his art. In paintings that essentially illustrated his own personal narrative, he suggested complex, multilayered stories that explored the timeless themes of man’s place in the natural world, remembrance, and mortality (Figs. 11, 12). All this is masterfully translated through design, color, and an obvious love of craft.

When Wyeth died suddenly in 1945, the news stunned his family as well as the world at large. His hope to be recognized among the highest echelon of American painters was not fully realized in his lifetime. The arbitrary distinctions that he felt segmented his career, however, have shifted and perhaps no longer seem valid. Wyeth’s oeuvre contains a range and diversity that endlessly delights, instructs, and inspires audiences of all ages.

|

Fig. 12: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), Island Funeral, 1939. Egg tempera and oil on hardboard, 44½ x 52⅜ inches. Brandywine River Museum of Art. Gift of E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company in honor of the 50th Anniversary of the Brandywine Conservancy & Museum of Art (2017). |

|

Fig. 13: N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), The Lobsterman (The Doryman), 1944. Tempera on hardboard, 23¼ x 47¼ inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Amanda K. Berls (1975). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY. |

N. C. Wyeth: New Perspectives at the Brandywine River Museum of Art (through September 15, 2019), was co-organized by the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and the Portland Museum of Art in Maine. Abbreviated versions of the exhibition will travel to the Portland Museum of Art (October 4–January 12, 2020), and to the Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio (February 8–May 3, 2020). The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue with contributions by D. B. Dowd, David M. Lubin, Kristine K. Ronan and Karen Zukowski (Brandywine River Museum of Art and the Portland Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press).

1. N. C. Wyeth to Sidney Marsh Chase, March 16, 1908, in The Wyeths: The Letters of N. C. Wyeth, 1901–1945, ed. Betsy James Wyeth (Chadds Ford, Pa.: Brandywine River Museum of Art, 2nd edition, 2008).

Christine B. Podmaniczky is the curator of N. C. Wyeth Collections & Historic Properties at the Brandywine River Museum of Art. Jessica May is the deputy director and Robert and Elizabeth Nanovic Chief Curator of the Portland Museum of Art.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2019 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.