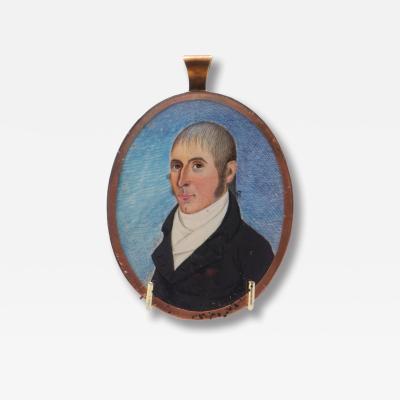

Collecting Art and Furniture at the New England Historic Genealogical Society

|

by Curt DiCamillo and Gerald W. R. Ward

|

| Detail images courtesy New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS); Incollect illustration. |

|

The fine art collection of American Ancestors/New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS)—the country’s founding genealogical institution—tells the story of America. From exceptionally rare seventeenth-century Boston portraits to images that portray the struggle of slavery, this important collection spans almost four centuries of American history. Many people—even those familiar with the organization—are not aware of the material within this institution. A new book—Family Treasures: 175 Years of Collecting Art and Furniture at the New England Historic Genealogical Society, published in 2020 to coincide with the 175th anniversary of American Ancestors—examines some of the collection’s most intriguing objects.

|

|

| The Hancock Chair, maker unknown, probably London, England, 1760–1770. Mahogany, beech, and spruce, with reproduction upholstery. H. 44 in., W. 31 in., D. 24 in. Gift of The Rev. Edmund Farwell Slafter, 1883 (R0001). |

John Hancock (1737–1793) inherited and lived in his uncle’s stone house on Beacon Hill, located to the left of the Massachusetts State House. Built in 1737 by Thomas Hancock (1703–1764) and his wife, Lydia Henchman (1717–1776), it was filled with fine furniture and objects acquired by Thomas, a wealthy merchant, and added to by his nephew, John. After John’s death in 1793, these objects were dispersed far and wide. This English easy chair is an important survivor. It may have been recorded in the “Great Chamber” in John Hancock’s estate inventory of 1794, as part of a room that contained a large suite of seating furniture upholstered in yellow damask that matched the window curtains. In 1978 fragments of the chair’s original upholstery were used by Scalamandré Silks of New York City, in consultation with Colonial Williamsburg and Winterthur, to manufacture the bright yellow worsted damask that covers the chair today. This chair was once part of a display at the former New England Historic Genealogical Society headquarters on Somerset Street, Boston, of early chairs associated with all six New England states; it is the only one known to survive.

|

|

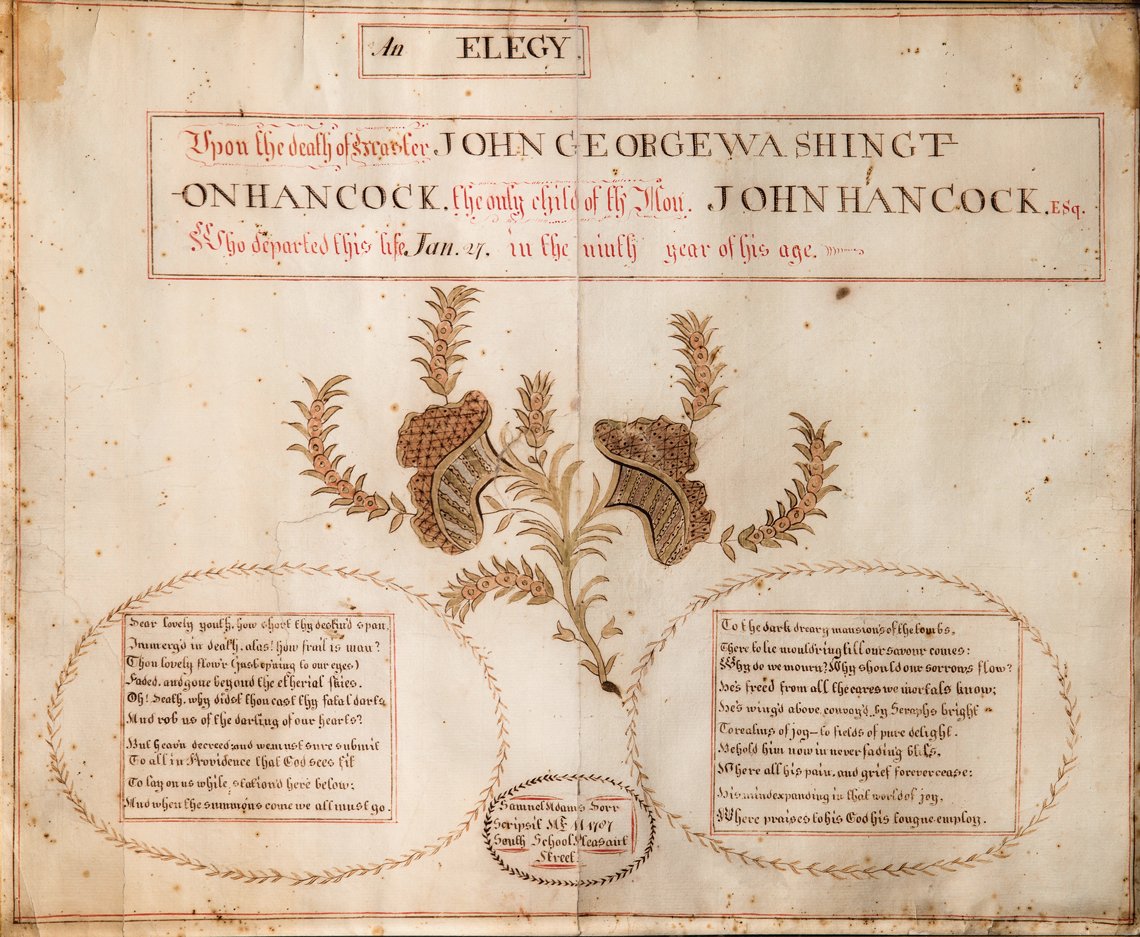

An Elegy Upon the Death of Master John George Washington Hancock, Samuel Adams Dorr, Boston, Massachusetts, 1787. Pen and ink on laid paper. 18 × 21 inches. Gift of Samuel Swett, 1859 (R0005). |

John Hancock and his wife, Dorothy Quincy, had two children, both of whom died young. Miniature portraits of both children, long misidentified, have recently been recognized and are in the collection of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, in Providence. Lydia Henchman Hancock, named for John’s aunt, died in 1777, when she was only nine months old. John George Washington “Johny” Hancock, was born in 1778. His tragic death, at age nine, on January 27, 1787, after an accident at a Milton pond, is memorialized in this penmanship exercise by a young student from the Pleasant Street School named Samuel Adams Dorr. Although Johny’s funeral was, in keeping with the custom at the time, a simple affair, two pieces of mourning jewelry created in memory of the young Hancock are in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A gold bracelet clasp contains strands of his hair, and a watercolor image that depicts a man and a woman, possibly meant to be John and Dorothy Hancock, flanking a memorial with the sentiment “GO SPOTLESS INNOCENCE TO ENDLESS BLISS.” The death hit John Hancock hard. He wrote in March to his friend Henry Knox that his “situation was totally deranged by the untimely death of my dear and promising boy.”

|

|

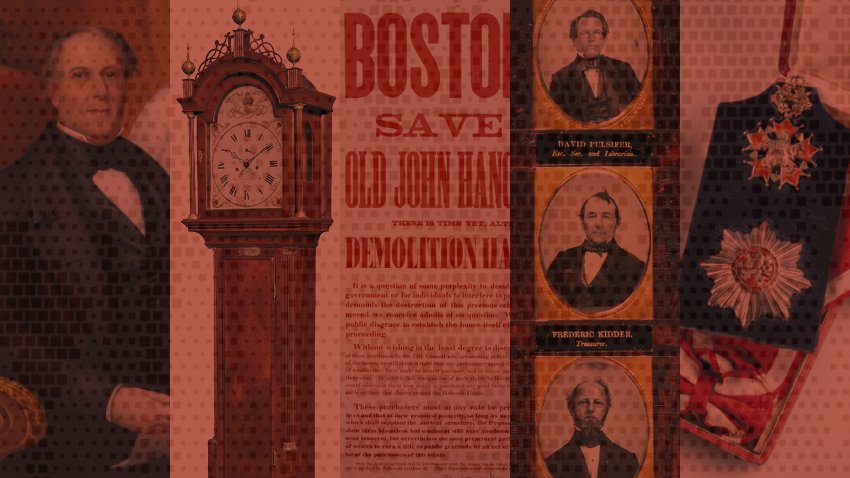

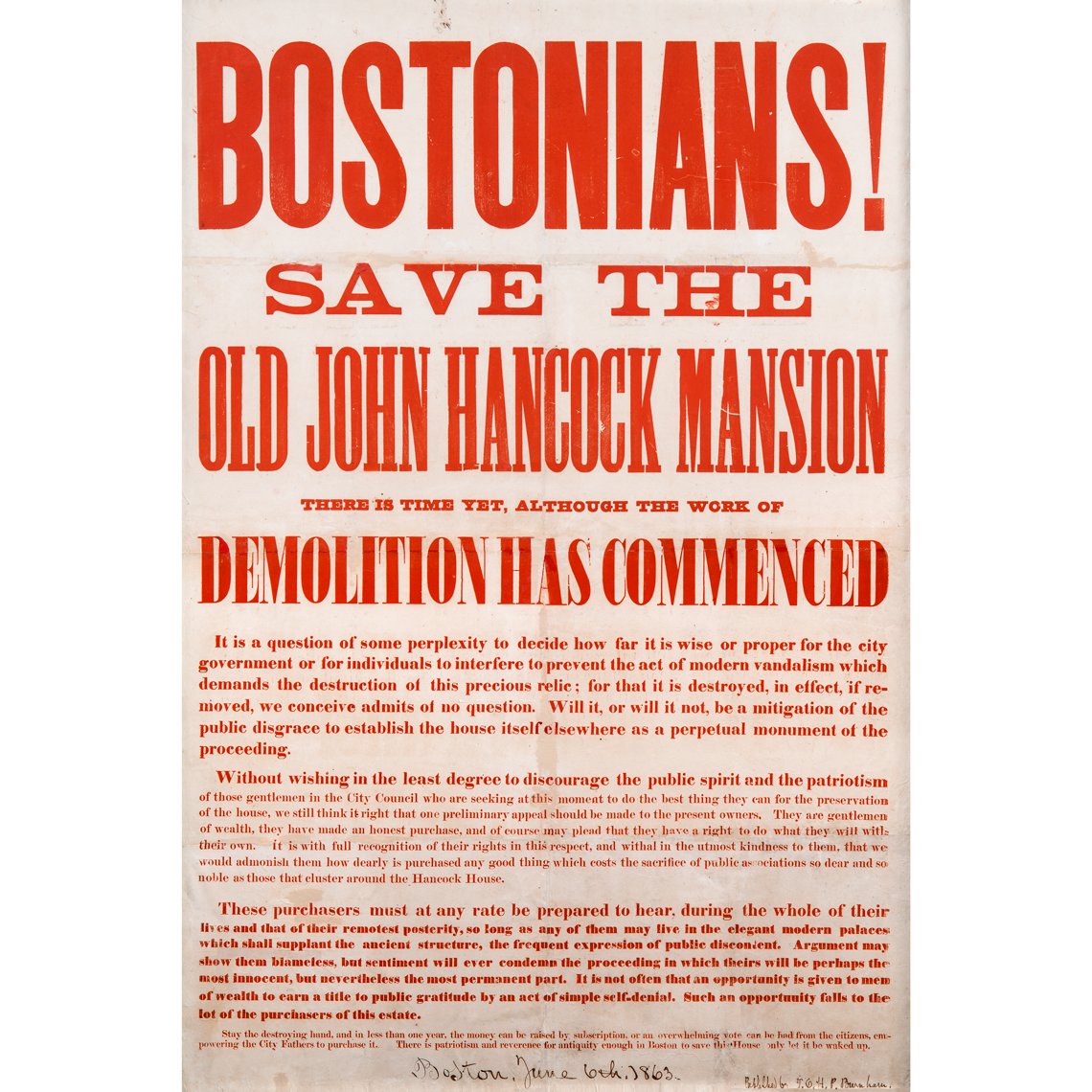

Save the Hancock Mansion Broadside, engraved by John Sartain (1808–1897), published by Thomas Oliver Hazard Perry, “Alphabet” Burnham (circa 1814–91), Boston, Massachusetts, dated June 6, 1863. Colored ink on paper. 45 × 31 inches. (R0006). |

The Hancock Mansion was threatened with demolition in the early 1860s. This large lithograph broadside was distributed in June 1863 throughout the city to protest the “act of modern vandalism, which demands the destruction of this precious relic.” This example is perhaps one of only two that survive; the other is in the collection of Historic New England, formerly the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, founded in 1910 by William Sumner Appleton. This brave effort to mobilize the public was unsuccessful, however, and the house was razed in 1863 in favor of, as the artist Edward Lamson Henry noted, “common modern houses.” These, in turn, gave way to a new wing of the State House in the early twentieth century. In death, however, the Hancock Mansion was transformed into a symbol of the colonial revival and the nascent historic preservation movement, and Henry’s photographs and painting of the house, today at Yale, were important parts of the Hancock Mansion’s legacy. In fact, it is not a stretch to say that the modern American preservation movement was born with the destruction of the Hancock Mansion.

|

|

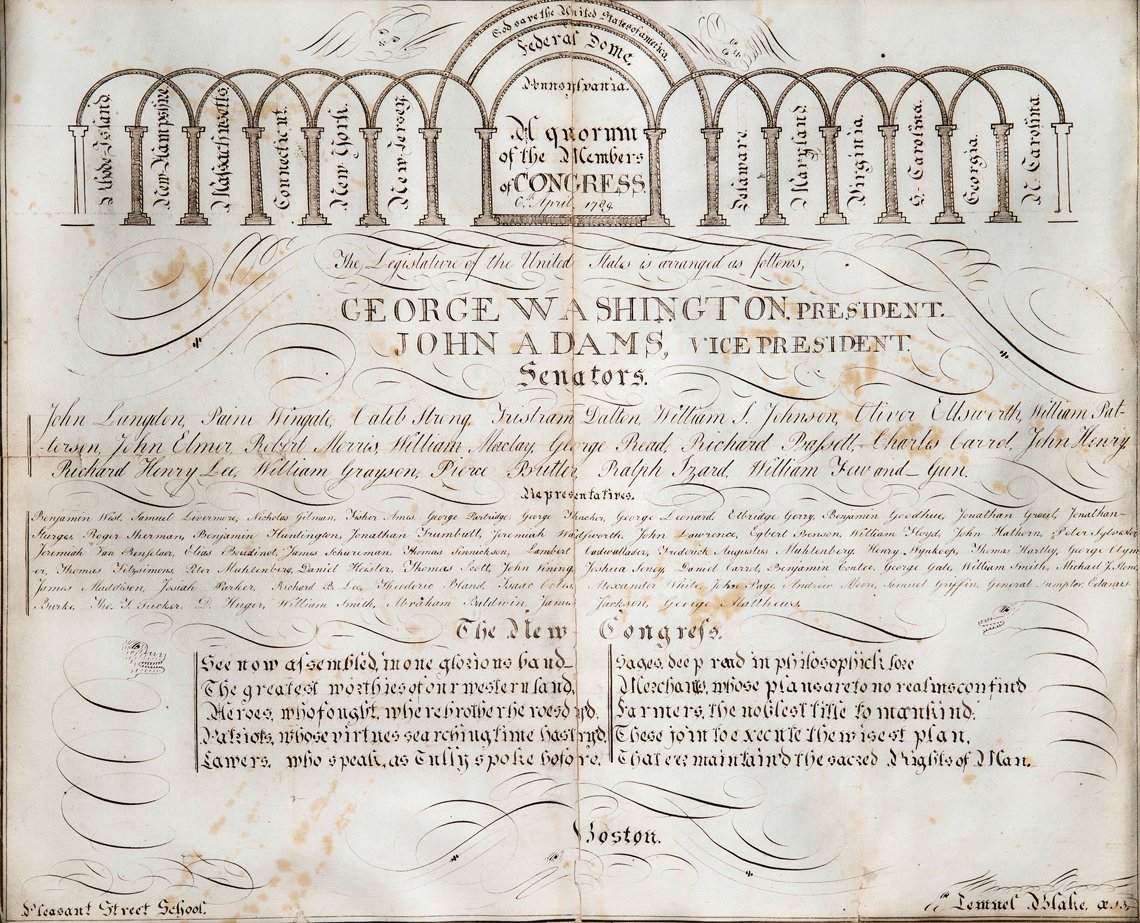

The First Congress, Lemuel Blake, Boston, Massachusetts, 1789. Ink on paper. 18 × 21 inches. Gift of the Dorchester Antiquarian and Historical Society, 1871 (R0407). |

This elegant exercise in penmanship by 14-year-old Lemuel Blake is a virtual snapshot of the birth of a new nation. It records the names of President George Washington, Vice President John Adams, and the various senators and representatives who were gathered in assembly in April 1789 as the first quorum held under the dome of Congress. The first Congress certified the Electoral College’s unanimous election of Washington and the election of Adams, who received thirty-four of the sixty-nine votes cast. The names of the thirteen original states are placed in an arcade at the top and interspersed with columns (the “Federal Pillars”) representing each state and its support of the Constitution and the new government. At the bottom is a poem, seemingly adapted from verse published in the Massachusetts Centinel of January 12, 1788, that characterizes the attendees at the Massachusetts convention to ratify the Constitution. Blake adopted its somewhat purple prose to apply to the new Congress. Lemuel Blake signed this work at lower right with his name and initials. He was born in Boston in 1775 and attended the South Writing School on Pleasant Street, as he indicates in the lower left corner. Clear and elegant handwriting was considered an essential part of the education of gentlemen and men of business. Blake’s mastery of the craft at age 14 is well demonstrated here.

|

|

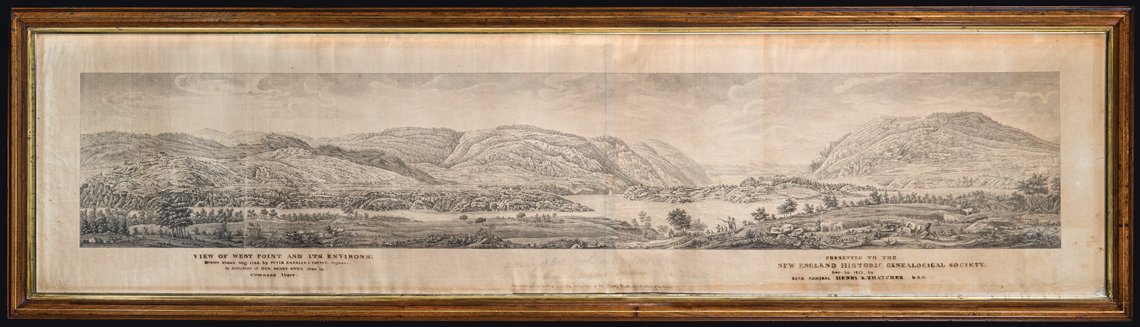

View of West Point and Its Environs, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, 1782. Pencil, pen, and ink on paper. 15½ × 55 in. Gift of Rear Admiral Henry Knox Thatcher, 1873 (R0411). |

In 1802, the United States Military Academy at West Point was founded under a directive of President Thomas Jefferson. Some twenty years earlier, General Henry Knox (1750–1806), long an advocate of a military training school, was in command of Continental Army troops in the area and was captivated by the location on an S-curve in the Hudson River. He commissioned this important panoramic view from Pierre Charles L’Enfant, his engineer, to record the topography and the scope of General Washington’s 10,000-man-strong encampment. West Point, located in the town of Highlands, New York, was identified by Washington as the most important strategic position in the colonies during the American Revolution, and is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the country. The impressive encampment depicted in L’Enfant’s sketch was a show of order and a demonstration of force by Washington’s Army at a time when the Revolution was still in doubt, even though the decisive battle at Yorktown had occurred the year before. The faint pencil inscription on this drawing is said to have been “in the autograph” of Henry Knox, grandfather of the donor.

|

|

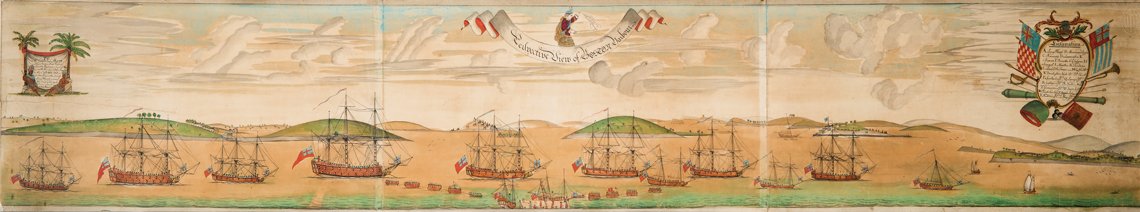

Perspective View of Boston Harbor, Christian Remick, 1768. Watercolor with pen and ink on laid paper. 135⁄16 × 64⅝ inches. Gift of Frederic Kidder, 1863 (R0442). |

Taken from the end of Long Wharf, this rare view of Boston Harbor depicts the landing of British troops in 1768, a crucial moment in the path leading to the American Revolution. To quell the Bostonians’ protests against the Townshend Acts, the Stamp Act, and other impositions by the Crown and Parliament, the British dispatched two regiments from Halifax, Nova Scotia, in October 1768. This perspective view by artist Christian Remick captures this unwelcome intrusion by the British; the irritating presence of the redcoats was one factor ultimately leading to the Boston Massacre of 1770 and subsequent events.

Little is known of Remick’s work. Born into an old Cape Cod family, and presumably an auto-didact, his day job was that of a sailor and mariner. He valiantly tried to make a career as an artist, however, and he advertised in the Massachusetts Gazette in 1769 that he “performs all sorts of Drawing in Water Colours” and also would color pictures and draw coats of arms (some of which survive). He noted that he had on exhibition versions of this watercolor and other examples of his work in the Golden Ball and Bunch of Grapes taverns, and also at Thomas Bradford’s house in the North End. Remick collaborated at least several times with Paul Revere. It is generally thought that Remick drew the image engraved by Revere for his own view of The Landing of the Troops in 1769; Remick hand-colored and signed at least one example. He also used watercolor and gold pigment to hand color versions of Revere’s print of The Bloody Massacre of 1770; an example, signed “Cold. by Christn. Remick” at lower right, is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Remick’s other notable accomplishment, a drawing of Boston Common featuring the Hancock Mansion, is in the collection of Historic New England.

|

|

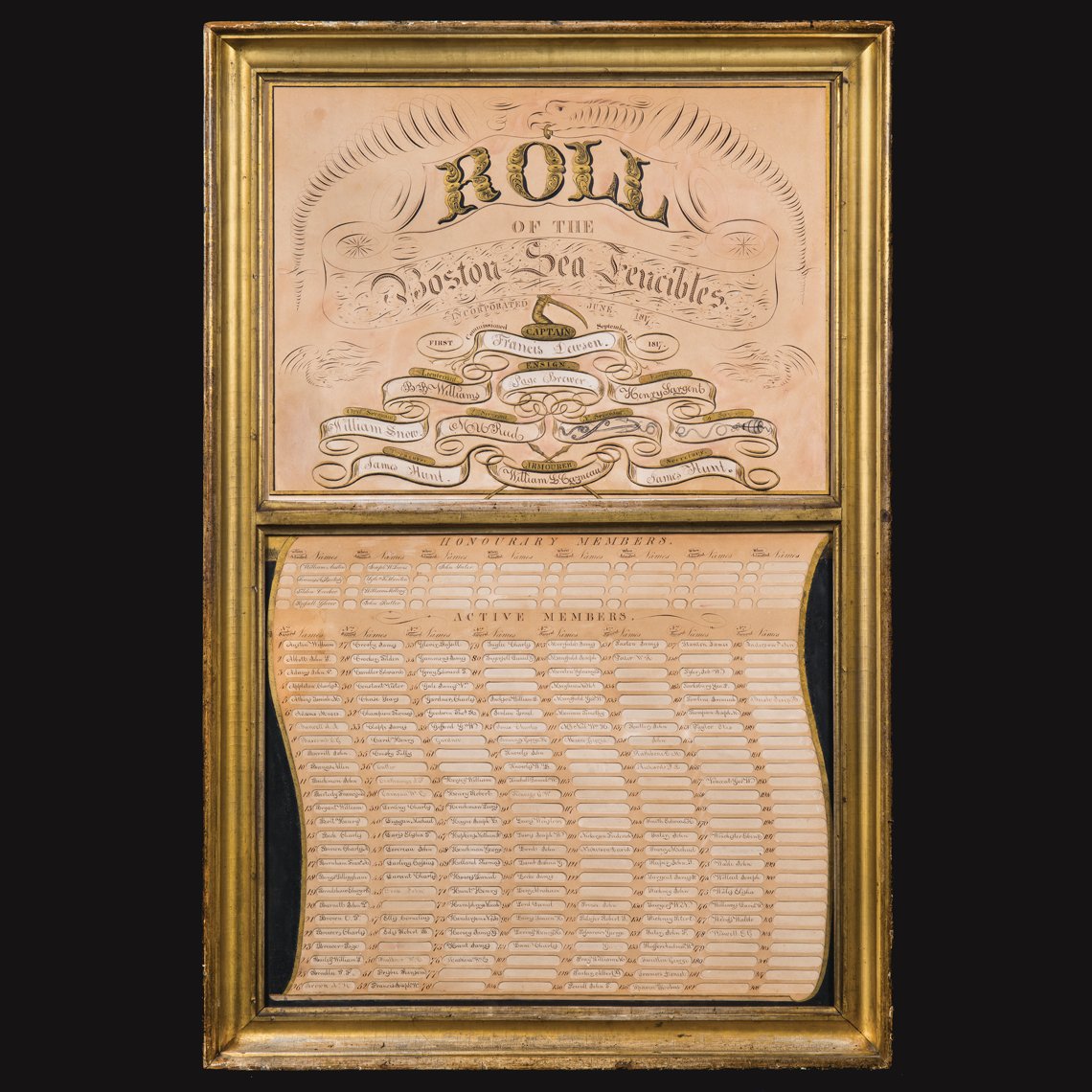

Roll of the Boston Sea Fencibles, Gershom Cobb, Boston, Massachusetts, 1824. Pen and ink on paper. 37 × 24 inches. Gift of Benjamin A. G. Fuller, 1876 (R0443). |

This large document displays the skills of Gershom Cobb, a little-known Boston bank clerk and writing master, who was a skilled calligrapher and artist. He was also a wood engraver, as evidenced by several bookplates and by an ambitious elegy for USS Chesapeake commander James Lawrence that was engraved on silk circa 1813; examples of the elegy are today at the Worcester Art Museum and the American Antiquarian Society. This roll must have been one of Cobb’s final works, as he died in Dorchester on October 3, 1825, aged 44.

The Boston Sea Fencibles, originally organized in 1813, trace their origin to the War of 1812, when, following an English and European practice, similar companies were formed for coastal marine defense in several American cities. Although most groups were disbanded after the war, the Boston Sea Fencibles, as stated on this document, were incorporated in June 1817. Membership consisted of “Masters and Mates of Vessels” living in Boston or within five miles who “are, or shall hereafter be exempted from, military duty.” In addition to their ostensible defense duties, the Boston Sea Fencibles also were a civic-minded service organization. Here, above the median strip, Cobb provides the names of the officers of the Boston Sea Fencibles, starting with the captain, and including the names of the ensign; two lieutenants; treasurer; ordinary, first, second, third, and fourth sergeants; armourer; and secretary. The lower section gives the names of several honorary members and a longer roster of active members.

|

|

Ambrotypes of Early New England Historic Genealogical Society Officers, David E. James & Co., Boston, Massachusetts, October 1858. Photographs set in mahogany frame. 21 × 18½ inches. (R0250). |

In October 1858, the New England Historic Genealogical Society took advantage of what was then still fairly new technology to compile this photo montage of twenty-four of its earliest officers, the oldest group image we have of the organization’s leadership and a sign of its maturation. The organization commissioned local photographer David E. James (active circa 1850s), located at 4 Summer Street, to prepare the photographs. At the same time, they created a similar array of forty of the organization’s earliest members. Each of these views contains small oval ambrotypes of an older white male, characteristic of the membership in its formative years (women were first admitted as members in 1898). Harvard had begun the tradition of class photograph albums in 1852, and the custom of taking photographic portraits of prominent individuals by famous photographers such as Matthew Brady was also becoming widespread. NEHGS was probably following suit by creating a record of their early leaders and members. James provided his patented ambrotypes for 25 cents each, and upwards. Developed in the early 1850s, ambrotypes were produced by commercial photographers as a less expensive version of a daguerreotype. Printed by a collodion process on a glass plate, as opposed to a silvered copper plate, ambrotypes were also one-of-a-kind images. James & Company was one of thirty-five photographers listed in the Boston Almanac for 1858.

|

|

The John Whorf Tall Case Clock, Simon Willard; dial painted by Spencer Nolan; cabinet work, possibly by Davenport. Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1817. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, white pine, light- and dark-wood inlay. 92 x 20 × 19⅞ in. New England Historic Genealogical Society purchase, 2017 (2017-021). |

The Whorf clock was made in the shop of Simon Willard, a well-known craftsman and the leading clockmaker of his generation in the Boston area. The case of this specimen is signed in chalk “Davenport March 1817,” possibly a reference to the cabinetmaker who fashioned it. The dial is attributed to the ornamental painter Spencer Nolan (1784–1849), whose neoclassical gilt and polychrome decorations add to the clock’s majestic appearance. The dial is inscribed “WARRANTED/BY S. WILLARD/for Mr. John Whorf.” John Whorf (1785–1854) of Provincetown, Massachusetts, was the owner of a prosperous cod-fishing business. The clock descended to his son Thomas (1815–1887), and eventually to his grandson, Philip A. Whorf (1841–1916), who gave it to the New England Historic Genealogical Society. The bequest is recorded on an engraved silver plaque attached to the front of the case. In 1982, NEHGS deaccessioned the clock to a dealer, and it eventually found its way into a private New York collection. Fortunately, it reappeared at a Sotheby’s auction in January 2017, where it was reacquired for NEHGS, as the gift of an anonymous donor.

|

|

John Singleton Copley (1738–1815), Mrs. Andrew Tyler (Mary Richards), ca. 1765–1767. Pastel on paper mounted on canvas, H. 27¼, W. 22½ inches. Gift of Captain George Jackson Tyler, 1850 (R0010). |

On March 20, 1745/46, sixteen-year-old Mary Richards (1731–1783) of Dedham, Massachusetts, married Reverend Andrew Tyler (1719–1777), a graduate of Harvard in the class of 1738 and the second minister of the Clapboard Trees Parish in Dedham from 1743 until his dismissal in 1772 for his royalist sympathies. She was the daughter of Colonel Joseph Richards, a physician, and Mary Belcher. The Tylers hired colonial America’s greatest portrait painter, John Singleton Copley (1735–1815), to capture this like-ness of Mary in about 1765. At the time, she was in her mid-30s, and Copley shows her in a blue dress with a pink mantle and a circlet of pearls around her neck. Jules David Prown noted that Copley painted Mrs. Tyler at a time when he “had hit his stride in the medium” of pastel. The Tylers knew Copley’s family socially, and in 1777 their daughter, also Mary—one of their nine children—married Charles Pelham, Copley’s half-brother. The portraits of Andrew (not shown) and Mary Tyler descended in the family to their grandson, George Jackson Tyler, who presented them to New England Historic Genealogical Society in 1850, only a few years after its founding.

|

|

Bass Otis (1784–1861), Lemuel Shattuck and Family, 1850. Oil on canvas, H. 60, W. 47⅜ inches. Gift of Lillian F. Thompson, 1920 (R0281). |

Lemuel Shattuck (1793–1859), one of the founders and the first vice president of New England Historic Genealogical Society, commissioned Bass Otis to paint this ambitious family portrait. Shattuck was an accomplished man. He was a teacher, bookseller, and publisher, a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and the Boston City Council, and one of the founders of the American Statistical Association. In 1839 Shattuck championed legislation to require a better system for the registration of vital information. After participating in the design and implementation of the Boston Census of 1845, he went to Washington to help design an improved federal census. His 1850 Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts (commonly known as the Shattuck Report) is considered one of the most significant documents in the area of public health. Shattuck has been memorialized in the name of a teaching hospital in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, and is honored at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, where his name appears on the frieze of the school’s building, together with twenty-two other visionaries in the area of public health.

In this group portrait, Shattuck is seated at left, with his wife, Clarissa Baxter (1797–1871), seated at the far right, hands crossed in her lap and her left arm resting on an urn. Their five daughters are also pictured. The 1850 date of this painting straddles several family threshold events. The wedding of Sarah White to her cousin, John Henry Shattuck (born 1819), on June 13, 1849, may have prompted its creation. However, the death of youngest daughter Frances on June 26, 1850, raises the possibility that Otis included her posthumously (at center with her elbow on the table).

|

|

Abraham Ratshesky’s White Lion Medal, Karnet a Kyselý, Prague, Czechoslovakia, circa 1932. Silver, silver gilt, gold, enamel, and ribbon; red leather case. Gift of the A. C. Ratshesky Foundation, 1987; Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center at NEHGS (1987.049). |

The recipient of this impressive medal, Czechoslovakia’s highest honor, was the renowned Abraham Captain “Cap” Ratshesky (1864–1943), who served under President Herbert Hoover as the American minister (officially Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary) to Czechoslovakia from January 1930 until May 1932. Born in Boston to Jewish immigrant parents (his father, Asher, was from Russia), Ratshesky rose to prominence in 1895 as the co-founder, with his brother Israel, of the United States Trust Company, a Boston institution willing to serve immigrants who were rebuffed by other banks. He became a Republican politician and legislator, philanthropist, and social activist, assisting the Red Cross, helping to save the USS Constitution, helping with World War I relief, and serving as president of the Massachusetts Public Safety Commission. He is best remembered today for his crucial role in spearheading relief efforts for Halifax, Nova Scotia, in December 1917, after the collision of the SS Mont-Blanc, a French munitions vessel, and the Norwegian ship SS Imo. The resulting explosion leveled much of the Canadian city, killing about 2,000 and injuring another 9,000. Ratshesky helped assemble a relief train that brought doctors, nurses, and medical supplies from Boston, fighting its way through a blizzard and deep snow drifts to reach its destination. To this day, the city of Halifax sends a Christmas tree to the city of Boston in gratitude for, and in memory of, the efforts of Cap Ratshesky and his colleagues.

|

|

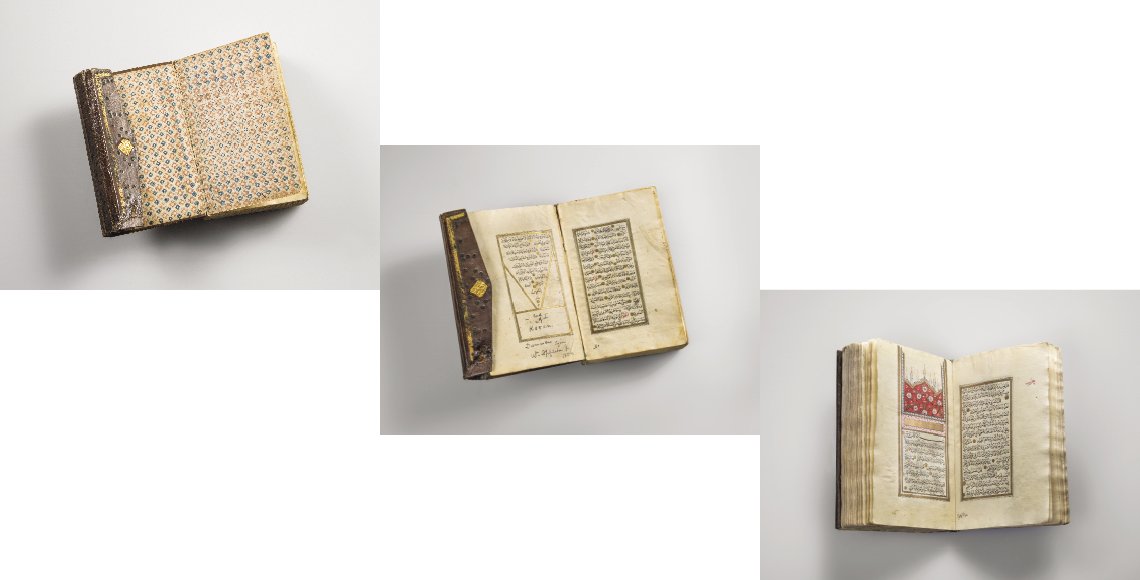

The Appleton Qur’an, maker unknown, probably Syria, mid-nineteenth century. Ink on paper; leather binding. 5⅞ × 3 × 1 in. Gift of William Joseph Warren Appleton Jr., 1864 (R0508). |

In 1864, William Appleton Jr. (1825–1877) donated this small Qur’an (Koran) to the New England Historic Genealogical Society. Appleton’s gift was aptly described as “an elegant Arabic Koran, written in an elegant hand, with an Introduction in illuminated letters.” The Society librarian noted that Appleton acquired it in Damascus, Syria, during his travels in 1854–1855 (the book contains Appleton’s note to that effect). In mid-nineteenth century New England, copies of the Qur’an were not unknown, but this was, nevertheless, a significant addition to the NEHGS library. By 1790, Harvard owned three copies of an English translation of the “Koran of Mahommed” published in London in 1734. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, among others, also owned copies. In June 1806, Isaiah Thomas, the famous early printer, published the first American edition of the Qur’an in Springfield, Massachusetts, printed by Henry Brewer. Appleton’s gift strengthened the holdings of important texts in their original languages at NEHGS.

William Appleton Jr. was the son of the very wealthy Boston merchant William Appleton (1786–1862) and his wife, Mary Ann. William Jr. married Emily Warren (1818–1905) in 1845, and was a life member of NEHGS, admitted in 1863. At his death, he was “kindly remembered by his companions who were his fellow travelers during a long and eventful journey in the East,” probably the trip during which he acquired this book. “He was of a retiring disposition, and distrustful of himself. This, with a delicate constitution, prevented him from engaging in active business.” Nevertheless, he was remembered for his “benevolence to the poor, and for his interest in and benefactions to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Dumb Animals.” He was noted for a map of early Boston that he re-created from documents, and for his publication in 1875 of the Narrative of Le Moyne, An Artist Who Accompanied the French Expedition to Florida under Laudonnière, 1564: with Heliotypes of the Engravings Taken from the Artist’s Original Drawings Translated from the Latin of De Bry, a volume also in the NEHGS collection. Appleton died at age 52 and is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

|

Family Treasures: 175 Years of Collecting Art and Furniture at the New England Historic Genealogical Society, by Gerald W. R. Ward, Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture Emeritus at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, includes a Foreword by D. Brenton Simons, President and CEO, American Ancestors, and a Preface by Curt DiCamillo, Curator of Special Collections, American Ancestors, both of whom aided the author in the selection of items for study and inclusion. For more details, visit shop.americanancestors.org.

Curt DiCamillo is Curator of Special Collections, American Ancestors / New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS).

Gerald W. R. Ward is the Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture Emeritus, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|