Artists on the Move: Portraits for a New Nation

|  | |

| Fig. 1: Cephas Thompson (1775–1856), Portrait of Thomas Williamson, Norfolk, Va., 1811–1812. Oil on mahogany panel, 15 x 12¼ inches. Museum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund (2007-89). | Fig. 2: Cephas Thompson (1775–1856), Portrait of Anne McClelland McCauley Walke Williamson, Norfolk, Va., 1811–1812. Oil on mahogany panel, 151⁄16 x 12¼ inches. Museum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund (2007-90). |

Portraiture was the dominant form of American painting in the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century. At first, the cost and limited availability of artists, most of them born abroad and influenced by English artistic trends, restricted painted likenesses to the upper class. To this small group, portraits were an expression of self-worth that reinforced or suggested wealth and social position. In the years after the American Revolution, an increasingly affluent and status-conscious middle class demanded access to material goods. This new rank of Americans used the portrait to express their pride in societal and economic accomplishments and their likenesses became a reflection of their own self-image. Increased desire for such portrayals led to an extraordinarily productive period between 1820 and 1840 for artists, many of whom were born in this country.

While elite academic artists focused on landscape and historical painting driven by English and European aesthetics, the majority of nineteenth-century painters in this country produced portraits in response to consumer demand. In an era before photography, portraiture served as the only means to capture a visual record of a person. They were important documents at a time when family units were vital to social and economic survival, especially during a period when mortality rates were high. Portraits also served as an expression of worldly status, and they filled the emotional need of sentimental remembrance.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s exhibition, Artists on the Move: Portraits for a New Nation, gathers together over thirty portraits painted between 1790 and 1840. Drawn from its decorative arts and folk art collections, the assemblage celebrates the rich visual breadth of work created in the formative years of this country. The show explores important concepts surrounding portraiture, including westward migration, regionalism, collecting, consumerism, artistic development, and nationalism. Selections also highlight the movement of artists from coastal regions to newly settled inland areas of the country. While as a whole the thirty plus portraits are a reflection of the ideals that embodied our new country, individually each painting represents the uniqueness of its subject, maker, and the time in which it was created.

Traditionally, the notion of artists traveling from town to town in search of commissions has focused on New England folk painters. But research reveals that a large number of geographically diverse portraitists, both academically inclined and self-taught, traveled not only within the northeastern United States but throughout the West and South. In pursuit of economic opportunity, painters followed potential leads near and far from home, often journeying into recently settled regions of the new nation. New England artists Cephas Thompson and Ralph E. W. Earl traveled to Charleston and to Nashville, Tennessee, respectively, in much the same way that midwestern painter Thomas Jefferson Wright journeyed to Philadelphia and French artist Francis Cezeron came to the mid-Atlantic region. Other artists like Charles Peale Polk worked regionally, traveling within a smaller geographic area.

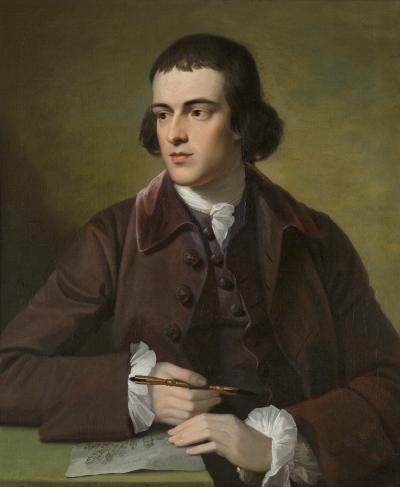

|  | |

| Fig. 3: Ralph E. W. Earl (1785/88–1838), Portrait of Thomas Claiborne, Nashville, Tenn., ca. 1825. Oil on canvas, 29½ x 24½ inches. Museum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund (2017-300). | Fig. 4: Ralph E. W. Earl (1785/88–1838), Portrait of Sarah Martin Lewis King Claiborne, Nashville, Tenn., ca. 1825. Oil on canvas, 29½ x 24½ inches. Museum Purchase (2017-301). |

Colorful descriptions of new lands lured painters and patrons alike to areas westward and south. For Pennsylvania-resident Josiah Espy, the enthusiastic accounts of the “beauty and richness of the Ohio Valley” motivated his journey west to Lexington, Kentucky, along with a desire to reunite with family who had relocated decades earlier.1 His own written and published description of the town as prosperous, and its comparison to Philadelphia must also have piqued the curiosity of other citizens eager to learn more about inland territories. As people moved, painters followed.

Some took advantage of local newspapers and announced their arrival in a town. The Massachusetts artist Cephas Thompson routinely informed residents when and where he could be “entirely devoted to their accommodation.” 2 The locations he worked in are also recorded in his surviving “Memorandum of Portraits,” along with the names of his sitters for the years 1806 to 1822.3 The book records 541 likenesses. He traveled to Virginia for the bulk of these commissions, visiting Alexandria, Richmond, and Norfolk for six consecutive winters.

Thompson rendered these rare small panel portraits of Norfolk banker Thomas Williamson and his wife Anne McClelland McCauley Walke Williamson, in Norfolk, Virginia (Figs. 1, 2). Like many painters, Thompson relied on the network of patronage for his commissions. His success in Virginia, seen in the completion of 104 canvases in only a six-month period, was no doubt in part due to the familial ties among his subjects, as well as word of mouth among his clients, all prominent citizens working as attorneys, bankers, politicians, and merchants. For Thompson, Williamson was an extraordinary connection. A self-described “patron of the arts,” Williamson reportedly added “some dozen” commissioned portraits by the artist to his painting collection.4

While Thompson returned home to Massachusetts in between his travels, fellow painter Ralph E. W. Earl relocated entirely from the region. After receiving training from his painter father, Ralph Earl, the younger Earl studied in London with American expatriates Benjamin West (1738–1820) and John Trumbull (1756–1843). In 1817, he returned to America with hopes of pursuing historical painting. His decision to depict the Battle of New Orleans took him to Nashville, Tennessee, where he rendered military heroes and met Andrew Jackson. The two formed a lifelong relationship that prompted Earl to follow Jackson to the White House and later to Jackson’s Tennessee home, the Hermitage, where the artist remained until his death in 1838. Earl found numerous commissions with Jackson and his friends and associates, including that of Thomas Claiborne, a major during the Creek War, and his wife, Sarah Martin Lewis King Claiborne (Figs. 3, 4).

Kentucky-born painter Thomas Jefferson Wright was among several first-generation artists from that region to move to Philadelphia with the hope of receiving artistic training from the acclaimed portraitist Thomas Sully.5 An extant letter from Lexington painter Matthew Harris Jouett to Sully was to introduce Sully to Wright, who, in his formative years as a painter planned a trip east to acquire additional training.6 The idea of connecting the two artists was purportedly the inspiration of Wright’s early patrons Cassandra Hukill Howard and George Gibson Howard, a dry goods merchant of Mount Sterling, Kentucky, with connections to Philadelphia (figs. 5 and 6). The Howards played a formative role in Wright’s artistic career by commissioning the youth to render their portraits and by introducing him to Jouett.

|  | |

| Fig. 5: Thomas Jefferson Wright (1798–1846), Portrait of George Howard, Mt. Sterling, Ky., ca. 1815. Oil on canvas, 29½ x 24½ inches. Museum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund (2015.100.1). | Fig. 6: Thomas Jefferson Wright (1798–1846), Portrait of Cassandra Hukill Howard, Mt. Sterling, Ky., ca. 1815. Oil on canvas, 29½ x 24½ inches. Museum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund (2015.100.2). |

| |

| Fig. 7: Thomas Jefferson Wright (1798–1846), Portrait of Elizabeth Thatcher Corbin Major Jameson, Culpeper County, Va., 1831. Oil on canvas, 27½ x 24 inches. Museum Purchase (2017.100.1). |

It is unknown whether Wright made his way to Philadelphia or spent any time in Sully’s studio since he disappears from the record for about nine years. With his reemergence comes a change in his style. In 1831, he received a large commission from the Major family in Culpeper County, Virginia.7 His more painterly approach to the portrait of William and Elizabeth Thatcher Corbin Major’s daughter “Eliza” Jameson suggests he received some sort of training in the intervening years (Fig. 7). Most notable is the artist’s depiction of an abundant amount of jewelry and hair ornaments, possibly implying a desire to showcase his knowledge of fashionable accoutrements.

For artists like French-born Francis Cezeron, travel to the United States was a chance for economic opportunity. Little is known about Cezeron’s training or even when or where he arrived in America. The earliest extant advertisement places him in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1805. For the next ten years, he traveled regionally to Carlisle and Pittsburgh; Frederick, Maryland; Culpeper County, Fredericksburg, and Loudon County, Virginia, the last where he rendered small panel paintings of brothers Stephens Thomson Mason and John Thomson Mason, great-nephews of George Mason, author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which later became the United States Bill of Rights (Figs. 8, 9). The likenesses are drawn in profile and bear a stylistic similarity to the early work of fellow Lancaster resident and painter Jacob Eichholtz suggesting that Cezeron may have taught Eichholtz to paint.8

The majority of Cezeron’s known subjects lived in the inland areas of the American backcountry, and his travel seems to have followed portions of the Great Wagon Road. As settlers moved westward, painters found increasing opportunities for portrait commissions in the towns that sprung up along established routes. No one demonstrated this better than Charles Peale Polk, who was raised in the household of his uncle, the painter Charles Willson Peale, but traveled throughout the region during his artistic tenure. Polk’s occupation took him to Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Alexandria, where, in 1785, he advertised in the local paper his availability to take “likenesses in oil” after having “finished his studies under the celebrated Mr. Peale of Philadelphia in Portrait Painting.” 9

|  | |

| Fig. 8: Francis Cezeron (1747–1828), Portrait of Stevens Thomson Mason, Loudoun County, Va., 1810–1815. Oil on tulip poplar panel, 14½ x 12½ inches. Museum Purchase (2010.100.3). | Fig. 9: Francis Cezeron (1747–1828), Portrait of John Thomson Mason, Loudoun County, Va., 1810–1815. Oil on tulip poplar panel, 14½ x 12½ inches. Museum Purchase (2010.100.4). |

|  | |

| Fig. 10: Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822), Portrait of Amos Morrow, Jefferson County, Va. (now West Va.), ca. 1800. Oil on canvas, 28⅛ x 25⅛ inches. Gift of M. Knoedler and Company, Inc. (1957.100.11). | Fig. 11: Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822), Portrait of Matilda Morrow, Jefferson County, Va. (now West Va.), ca. 1800. Oil on canvas, 28⅛ x 25⅛ inches. Gift of M. Knoedler and Company, Inc. (1957.100.12). |

The training Polk received from his famous uncle is easily seen in the two portraits of Amos and Matilda Morrow (Figs. 10, 11).10 The swagged red curtain used as a backdrop and the feigned oval framing devices appear in many of Peale’s pictures. Yet Polk’s effort to produce faithful likenesses distinguishes his work, in particular his fascination with detail, which was carried to the extreme by the inclusion of Amos’ scalp tumors. Although unsigned, the paintings were rendered in Jefferson County, West Virginia (then Virginia), most likely in the late 1790s, when the artist traveled to western areas of Maryland and Virginia.

Artists on the Move: Portraits for a New Nation opens November 18, 2017 and runs through December 31, 2019 at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum at Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia.

All images appear courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Laura Pass Barry is the Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. January 1811 issues of the Norfolk Gazette and Public Ledger and Norfolk Herald.

3. “ Cephas Thompson’s Memorandum of Portraits,” in the Boston Athenaeum. A reprint published privately in 1965 is available in at least twenty-two libraries, including the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg. See also Deborah L. Sisum, “A Most Favorable and Striking Resemblance,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 23, no. 1 (Summer 1997): 1–101.

4. See Diary of William Dunlap (1766–1839): The Memoirs of a Dramatist, Theatrical Manager, Painter, Critic, Novelist, and Historian, Vols. 2–3 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1930), 489.

5. See Estill Curtis Pennington, Lessons in Likeness: Portrait Painters in Kentucky and the Ohio River Valley, 1802–1920 (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2011) for a record of several dozen artists who traveled east to Philadelphia.

6. Edna Talbott Whitley, Kentucky Ante-Bellum Portraiture (Paris, KY: privately printed for the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, 1956), 783–4.

7. The author wishes to acknowledge Lea Lane for her research on the artist and his Virginia works.

8. Thomas R. Ryan, The Worlds of Jacob Eichholtz: Portrait Painter of the Early Republic (Lancaster, PA: Lancaster County Historical Society, 2003), 61–62.

9. The Virginia Journal and Alexandria Advertiser, 30 June 1785.

10. Polk’s portraits of the Morrows’ two daughters, also owned by Colonial Williamsburg, are similar in composition.