Pattern & Purpose: American Quilts at Shelburne Museum

|

Fascinated by design elements of color, pattern, line, and construction, and eager to recover a quintessentially “American” form of material culture, Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb (1888–1960) was one of the first to exhibit quilts as works of art in a museum setting. Mrs. Webb established the nucleus of Shelburne’s collection with over 400 historic bedcoverings in the 1950s. Today, Shelburne Museum is known internationally for the exceptional variety and quality of its collection, which is particularly strong in its holdings from nineteenth-century Vermont and New England.

Throughout the history of quilt-making, the finest pieces were often made to be admired rather than used. Brought out on special occasions, highly prized bedcovers linked family and community histories, bridging the gap between domestic life and public display. Young women often created quilts as part of their dowries, and quilts were gifted as expressions of friendship, devotion, or charity. By the middle of the nineteenth century, adept quilt-makers competed for prizes and local renown at state and county fairs. Today, quilt-making is recognized as an art form in its own right, revealing makers’ skills and personal visions—from complex geometric designs that would feel at home in a gallery of Pop Art to delicate patterns drawn from nature. Bringing together twenty masterpieces dating from the first decades of the 1800s to the turn of the twenty-first century, Pattern & Purpose explores objects that expand our sense of what art can be, and recognizes how invention and discovery can be found in the most familiar of places.

|

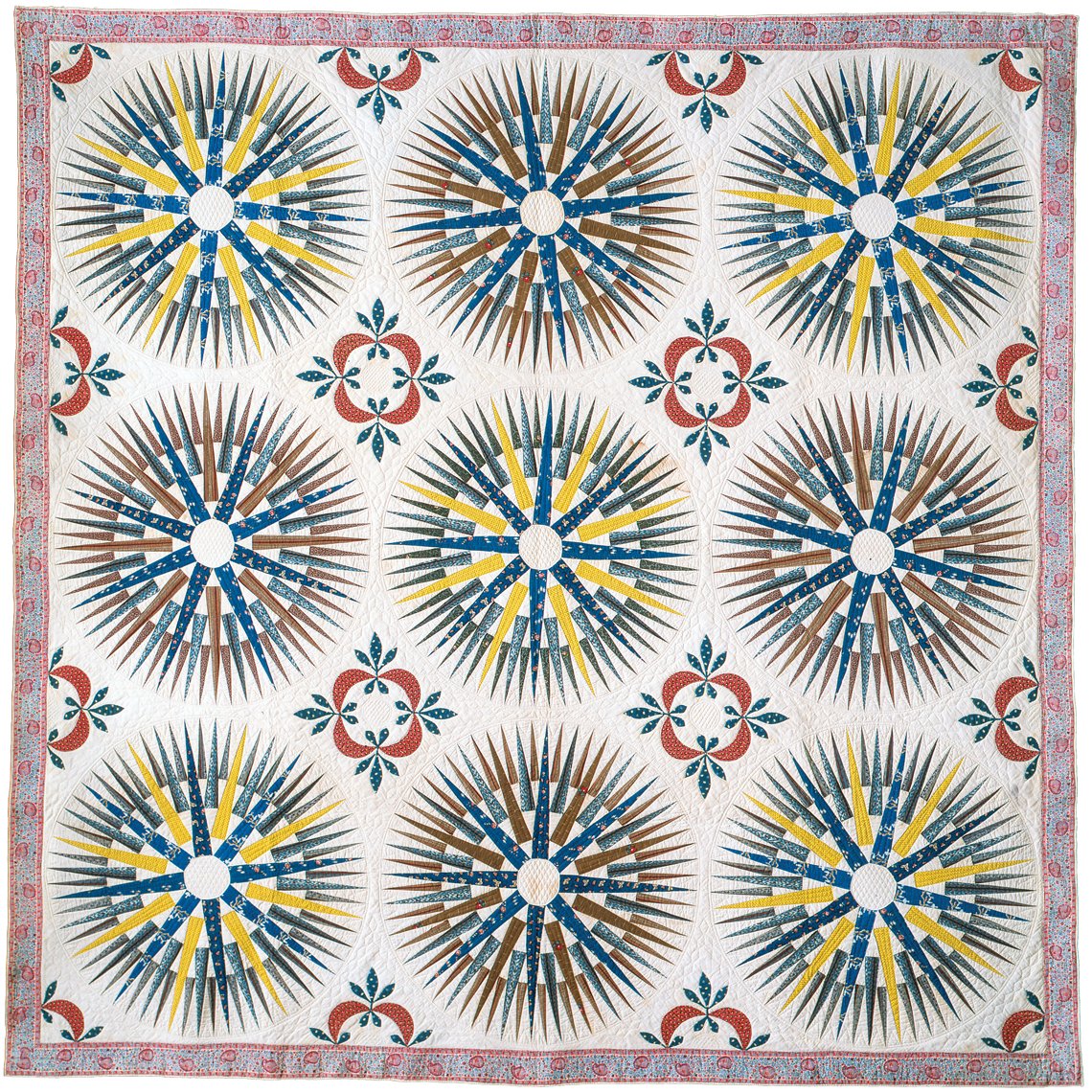

| Attributed to Emeline Barker (New York, N.Y., 1820–1906), Appliqué and Pieced Mariner’s Compass and Hickory Leaf Quilt, ca. 1860. Cotton, 100 x 96 in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Museum purchase, acquired from Florence Peto (1952-545).. |

When Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb acquired this quilt from legendary collector and textile historian Florence Peto (1881–1970) neither Webb nor Peto knew the identity of the bedcover’s maker. Rather, they were likely drawn to the variety of bright, printed cotton fabrics and the precise geometry of the quilt’s nine carefully pieced sixty-four-point “Mariner’s Compass” or “Rising Sun” blocks. Research by Deborah Lyttle Ash has connected this quilt to a remarkably similar bedcover in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York made with similar materials, quilting, and almost identical sixty-four-point compasses marked “Emeline Barker #7” in one corner.

|

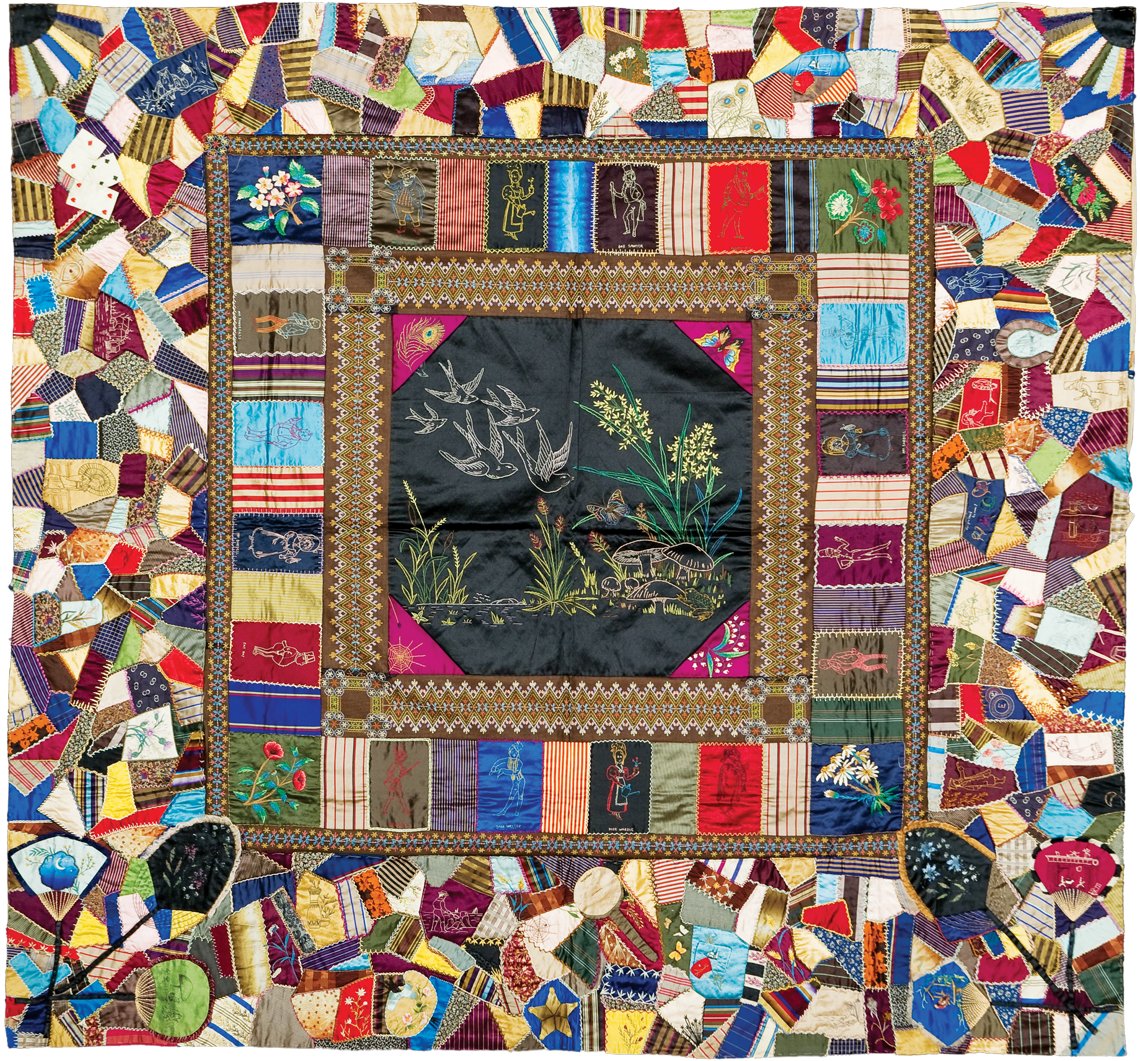

| Ella Chase (Derby Line, Vt., dates unknown), Pickwick Papers, 1890–1900. Cotton, polyester, and silk, 63½ x 67½ in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Gift of the Family of Paul A. Taylor (2010-1.1). Photography by Andy Duback. |

Made by Ella Chase when she was teaching sewing in New York City during the final decade of the nineteenth century, this remarkable medallion-style quilt features a central, embroidered panel with a band of swallows flying over a pond with mushrooms, wildflowers, a butterfly, and a frog. Surrounding the central panel are 16 rectangles depicting characters from Charles Dickens’s popular 1836–37 series, “Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club.” The embroidered figures were likely based on period drawings that appeared in Joseph Grego’s Pickwick Pickwickiana, an 1889 compilation of 350 unauthorized illustrations created throughout the nineteenth century.

|

| Jane Morton Cook (Scituate, Mass., 1730–?), Broderie Perse and Paper Pieced Charm or Honeycomb Patch Counterpane, 1810–25. Cotton, 99 x 115 in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Museum purchase (1957-524). |

In January 1835 Godey’s Lady’s Book published the first commercially available quilt pattern in America, naming it “hexagon patch-work.” The publication noted, “Perhaps there is no patch-work that is prettier or more ingenious than the hexagon, or six-sided; this is also called honey-comb patch-work. To make it properly you must first cut out a piece of pasteboard of the size you intend to make the patches, and of a hexagon or six-sided form. Then lay this model on your calico, and cut your patches of the same shape, allowing them a little larger all around for turning at the edges.” This classic pattern remained popular with quilters well into the twentieth century.

|

| Henrietta Winter Harvey (Columbus, Ks., 1859–1954), Appliqué and Pieced Autumn Leaves Medallion Quilt, 1938–40. Cotton, 88½ x 84 in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Gift of Nancy Willis in Memory of Mary Gail (Harvey) and Harry Lehrer (2010-10). Photography by Andy Duback. |

The bright pastel fabrics used in this Appliqué and Pieced Autumn Leaves Medallion Quilt, sometimes known as “Easter egg colors,” were most popular after 1925. The maker of this quilt, Henrietta Winter Harvey (1859–1954), was born in Pleasantville, Ohio. Around 1883, she moved with her family to western Kansas to homestead. She married and settled in Columbus, Kansas. Around the age of 80, she made this exceptional bedcover as a wedding gift for her granddaughter, who was married in 1940.

|

| Attributed to Minnie Melissa Burdick (North Adams, Mass., 1857–1951), Burdick Childs Quilt, 1876. Cotton and silk, 79 x 79¾ in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Museum purchase (1987-40). Photography by Andy Duback. |

The thirty-six blocks in this quilt illustrate scenes of family and domestic life in North Adams, Massachusetts, as well as biblical themes, such as the story of Jonah and the whale. Additionally, the Centennial Exposition of 1876 inspired two of the blocks. Held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, this event commemorated the one hundredth anniversary of America’s independence. The spectacle was widely publicized and lavishly described and illustrated in popular journals of the time. These reports might have served as a guide for the buildings featured in this quilt: one of the buildings closely resembles Memorial Hall, the key architectural structure of the Exposition, and another depicts the Women’s Pavilion. At the Exposition, this building was exclusively devoted to displaying artworks and products resulting from women’s labor.

|

| Carolyn Carpenter Smith Persons (Northfield, Vt., 1835–1902), Appliqué and Pieced Sunflower Quilt, 1860–80. Cotton, 77¾ x 85½ in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Gift of Ethel Smith Washburn (1987-19). Photography by Andy Duback. |

The tall sunflowers appliquéd and quilted on this bedcover may have been inspired by the mid-nineteenth-century design vocabulary of the English Arts and Crafts Movement, which was widely known in America through books and magazines. This movement advocated for traditional craftsmanship using high-quality materials, and often emphasized flat or streamlined naturalistic motifs. The stylized flowers, leaves, and stems of this eye-catching bedcover were appliquéd onto the white background, which is richly textured with hand-quilted stitches. The maker, Carrie Carpenter (1835–1902), inscribed her name on the back of the quilt.

|

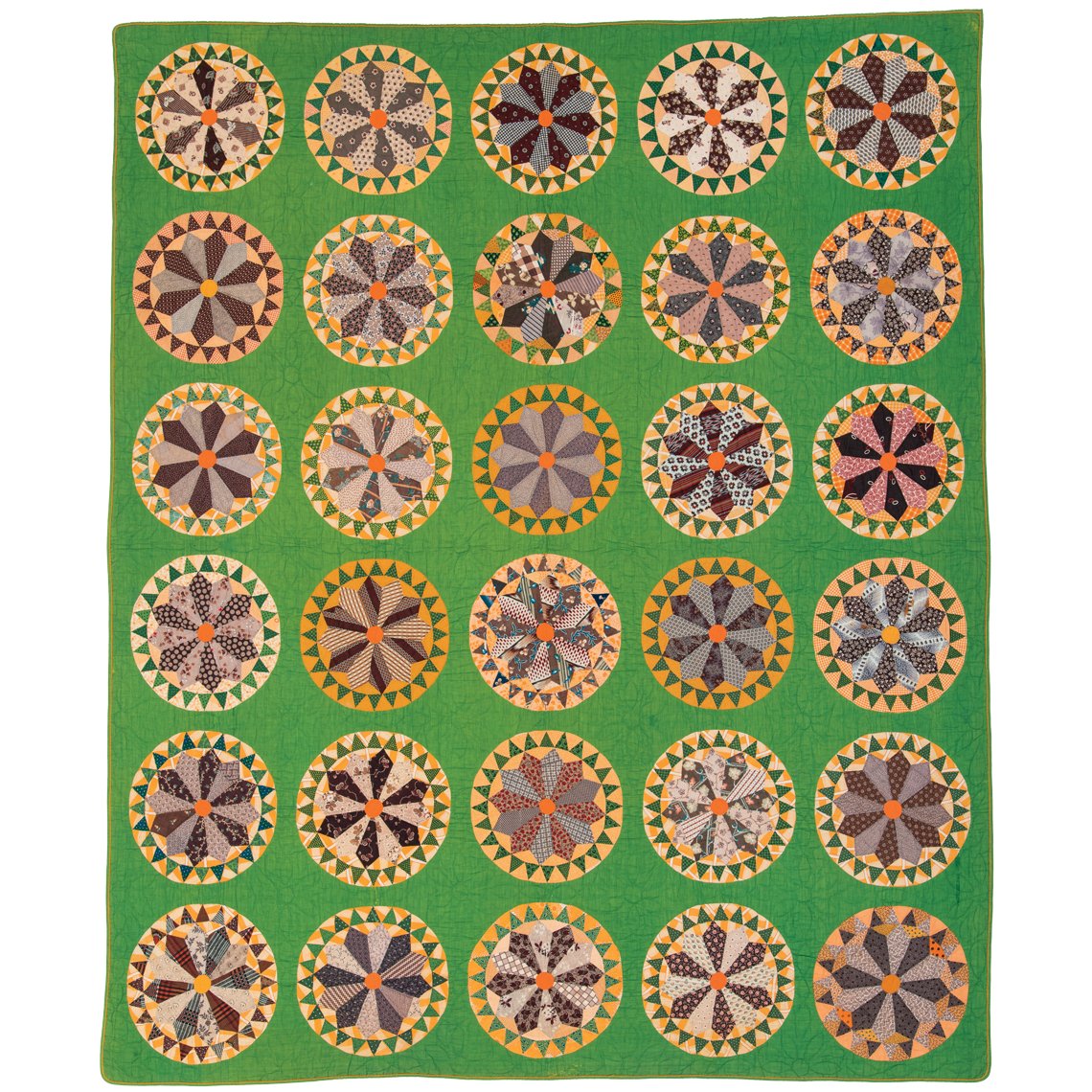

| Attributed to Emeline G. Perry Proctor (Fair Haven, Vt., 1849–1936), Pieced Pyrotechnics Quilt, late nineteenth century. Cotton, 91½ x 76 in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Bequest of Hazel Proctor Ibbotson (1994-3.1). Photograph by Andy Duback. |

Emeline Proctor (1849–1936) may have been inspired to create this vibrant green, yellow, and purple bedcover via the Ladies Art Company, the first known manufacturer to offer mail-order block patterns. Established in 1889 in St. Louis, Missouri, patterns were priced at 10 cents each, printed on heavy cardboard, and housed in a small paper envelope with a 3-inch color card of the block. By 1895, advertisements suggested that the Ladies Art Company offered as many as 272 quilt block patterns. In 1897 the company published its first printed catalog, offering upwards of 400 designs. This catalog had an enormous influence on the naming of block patterns, and the convenience of mail order quilting supplies for quiltmakers living in rural towns like Fair Haven, Vermont, cannot be overstated. An almost identical pattern to the compass-like “pyrotechnics” blocks featured on this bedcover was listed as no. 176 in the 1897 catalog and may have been the inspiration for Emeline’s quilt.

|

| Unidentified maker (Ohio), Appliqué and Pieced Four Little Birds Quilt, 1860–80. Cotton, 85¾ x 82⅛ in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Museum purchase, acquired from Florence Peto (1955-644). Photography by Andy Duback. |

In 1939 renowned quilter, collector, and historian Florence Peto (1881–1970) remarked, “my photographs of American-made quilts, spreads, and woven coverlets number over three hundred—all have authentic histories verified by family records and papers. What I desire to do in gathering this material [is to] preserve the memory and identity of the quiltmaker as well as her needlework.” Peto’s approach to research and documentation appealed to Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb (1888–1960), and for more than a decade Peto advised Mrs. Webb on acquisitions for the museum’s textile collection. Thought to have been made in Ohio between 1860 and 1880 because of a handful of other dated quilts with similar baskets, Mrs. Webb purchased this remarkable appliquéd bedcover from Peto in 1955.

|

| Unidentified Odawa maker (Peshawbestown, MI), Appliqué and Pieced Star of Bethlehem Quilt, 1900–25. Cotton, 78 x 70 in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Gift of John Wilmerding (1988-16). |

This quilt, the only bedcover in Shelburne’s collection made by a Native American, combines a central, pieced star pattern with blocks of appliquéd flowers forming the border. While we do not know the identity of the maker of this particular bedcover, research by Marsha MacDowell and Minnie Wabanimkee has illuminated a group of Odawa women who quilted together during the first quarter of the twentieth century in the basement of the St. Kateri Tekakwitha Church, a Catholic Church on reservation land held by the Grand Traverse Tribe of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. Several bedcovers created by these women are in the collection of the Michigan State University Museum and share the bright printed cotton fabrics, kaleidoscopic, radiating stars, and distinctive four- and five-petal floral motifs that distinguish Shelburne’s quilt. These decorative elements are typical components of Odawa craft, and mimic motifs found in earlier porcupine quillwork and beaded decoration from indigenous communities in the Great Lakes region.

|

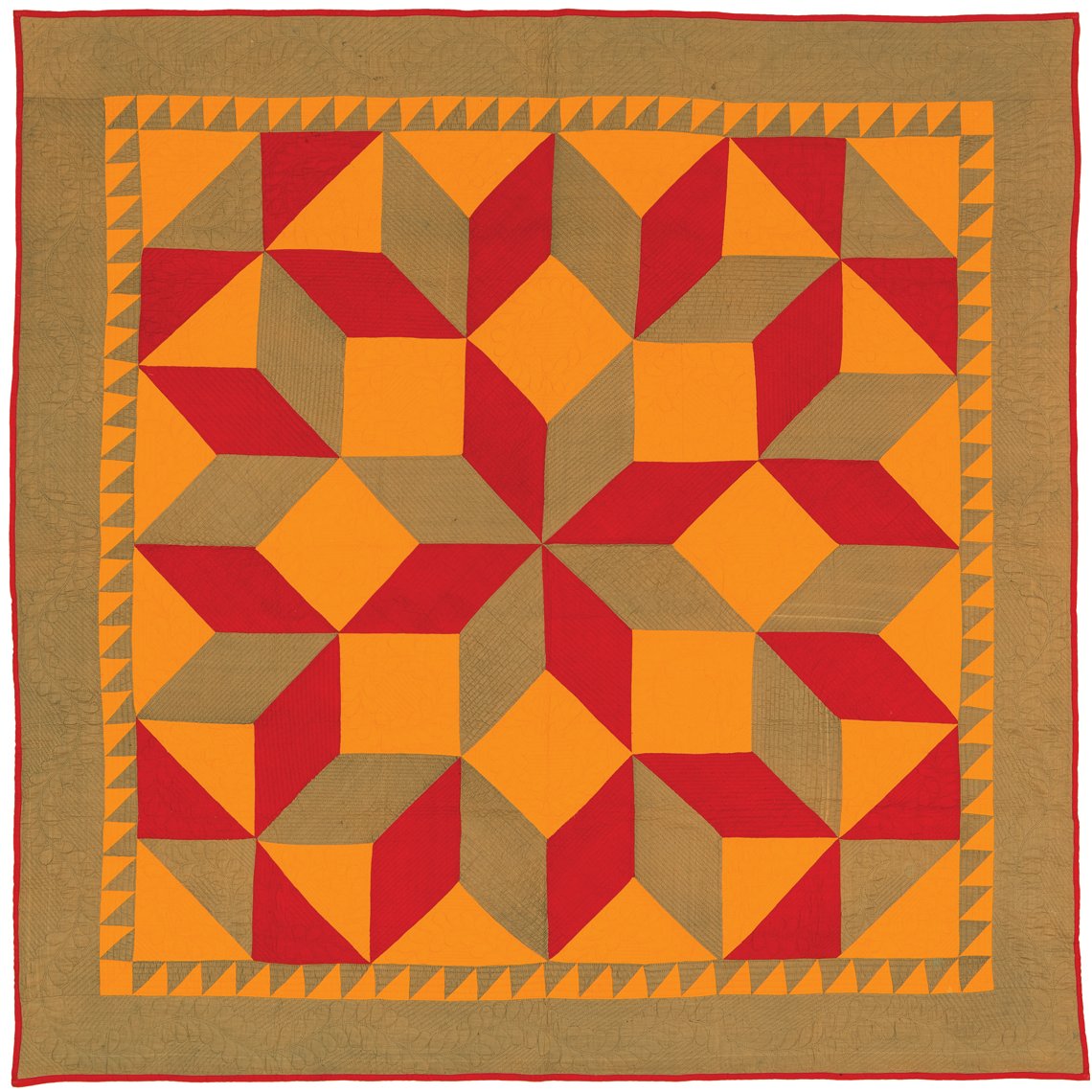

| Unidentified maker (Pennsylvania), Pieced Mennonite Broken Star Medallion Quilt, 1890–1910. Cotton, 78½ x 78½ in. Collection of Shelburne Museum; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Michael Polemis (2006-13.10). Photography by Andy Duback. |

Using simple combinations of diamonds and squares, the maker of this Broken Star Medallion Quilt has created an optical illusion of cubes, hexagons, and stars. Achieving the look of the stacked cubes requires three fabrics in varying intensities of color—one dark, one medium, and one light. Collectors and historians have lauded eye-catching Amish and Mennonite quilts since the 1970s for their geometric design sense, liberal use of jewel-like fabrics, and carefully quilted feathers, scrolls, and other motifs.

Pattern & Purpose: American Quilts at Shelburne Museum is an online exhibit available at shelburnemuseum.org/online-exhibitions. It is the twelfth online exhibit the museum has presented since the pandemic. While Shelburne is temporarily closed to the public, it continues to deliver the museum experience digitally.

Katie Wood Kirchhoff, Ph.D., is associate curator at Shelburne Museum.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|