Peabody Essex Museum’s New Gallery of Native American and American Art

by Sarah N. Chasse, Karen Kramer and Lan Morgan

|

by Sarah N. Chasse, Karen Kramer and Lan Morgan

Since its founding in 1799, the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) has collected and exhibited Native American art and culture as well as the fine and decorative art traditions of the United States. Celebrating the aesthetic strengths of PEM’s holdings, a new installation opening February 26, 2022 will include over 250 works across media, including sculpture, paintings, textiles and costumes, furniture, decorative arts, works on paper, archaeology, installations, and video. Artworks will span in time from 10,000 years ago to the present. The installation will integrate these collections across 10,000 square feet and will be on view for a ten-year period.

PEM has the oldest ongoing collection of Native American art in the western hemisphere, world-renowned for its outstanding aesthetic quality, condition, provenance, and span of time, media, and geography. As a thought-leader in the field, the museum has been exhibiting contemporary and historic Native art together since 1995, demonstrating continuity in creative expression and making select contemporary acquisitions to accelerate that dialogue. >>>

|

|

Patrick Dean Hubbell (b. 1986), Diné (Navajo), born 1986, HONORING OUR FOREMOTHERS, 2020. Oil, acrylic, and natural earth pigment on canvas. H. 72¾, W. 51⅞, D. 1¼ in. Gift of Burt and Lydia Adelman (2021.8.1). © Patrick Dean Hubbell. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by Kathy Tarantola. |

Patrick Dean Hubbell’s arrangement of black and white stars and stripes references the instantly recognizable iconography of the American flag and the geometric lines in Diné (Navajo) textiles. His highly expressive mark-making in the form of T-shaped crosses evokes the flag’s stars and symbolizes Spider Woman, an important figure in Diné cosmology who taught her people how to weave and create beauty. The title refers to two key points for the Diné: the importance of matrilineal descent, the line from a female ancestor to a descendant; and the interconnected relationship with the natural world in which Navajo philosophies are rooted.

|

Alan Michelson (b. 1953), Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), edition 1/3, 2018. High-definition video, bonded stone replica of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s late 1700s bust of George Washington, antique surveyor’s tripod, and artificial turf. Sound: members of Six Nations of the Grand River Territory. Digital video looped, 5:57 minutes. Dimensions variable. Museum purchase, by exchange (2019. 2019.38.1AB). © Alan Michelson. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum. |

Alan Michelson’s Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer) is a critical intervention about early American figures. Michelson projects historical maps, documents, portraits, and site markers onto a reproduction of George Washington’s bust. The archival images trace the history of the 1779 campaign against the Haudenosaunee people. General Washington ordered “total destruction and devastation” of their homelands in current-day upstate New York in waging the American Revolution. Led by Major General John Sullivan and Brigadier General James Clinton, the troops seized livestock and goods and burned sixty villages to the ground. Washington’s armies forced more than 5,000 Haudenosaunee to flee as war refugees and experience land dispossession, famine, and death. These actions earned Washington the name Hanödaga:yas, or “Town Destroyer,” which singers chant in various dialects. Michelson’s work prompts us to consider whose stories have defined America, and ask, are we ready to acknowledge new stories?

|

Marie Watt (Seneca, born 1967), Companion Species: Cosmos, Sunrise, Flint, Seneca, 2019–2021. Reclaimed wool blankets and embroidery thread, 116 x 220 inches. Museum purchase by exchange. Peabody Essex Museum (2021.4.1). Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Kevin McConnell. |

In the Seneca Creation Story, before the Earth existed, humans lived in the Sky World. Sky Woman fell through a hole in the sky (she may have been pushed), and as she fell, birds softened her landing. A motley crew of four-legged animals helped her to survive in this new place, which came to be known as Turtle Island (also known now as North America). The birds and animals are the first teachers. Cosmos, Sunrise, Flint speaks directly to this Creation Story. “When one is raised to think of animals as teachers and also as extensions of us—our relatives or relations—you’re less likely to be able to separate how our actions affect the environment, animals and the natural world,” says Watt. In collaboration with PEM, Watt hosted five sewing circles for participants to co-create. Together they embroidered blanket fragments with evocative words and phrases. Watt stitched the panels together into the final monumental artwork. Ultimately, through this piece, Watt asks us all to consider: What would the world look like if we thought of ourselves as companion species? Place, nations, generations, beings. All interconnected. Moving through the world, nurturing these relationships.

|

Pouch, Northeastern Native artist, name once known, Western Mass. late 1600s to mid-1700s. Deerskin, porcupine quills, porcelain beads, animal hair, and metal, 8 x 7 inches. Gift of Edward S. Moseley, 1979 (E28561). Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by Kathy Tarantola. |

This elegant draw-string pouch—likely worn in the belt of the artist’s husband for carrying tobacco—was transformed into a portable work of art, and a profound container of her worldview. Among Native cultures of the Northeast, the earthly cosmos is inhabited by humans, animals, and supernatural beings. Here, benevolent and malevolent forces are in a constant state of flux. Humans and animals are kindred spirits, and animals are honored for their spiritual powers. Thus, only with its consent and in times of need can a hunter take the life of an animal, appeasing its spirit with a prayer offering of tobacco. This deerskin pouch can be understood as a reverent symbol of the hunted: the pull ties possibly becoming legs and decorative perforated leather tabs suggesting ears or beaver tails. Symbolizing the earthly axis through which humans and spirits could communicate, the equal-armed cross motif finds visual and ideological affinity with the cascading delicate double-curved motifs on the pouch’s obverse. In the Northeast, double-curves signify balance—a concept further articulated in the double-sided nature of the pouch itself. Emblematic of the vital confluence between humans and animals, this pouch ensured the survival of the artist’s family and community through the maintenance of cosmological equilibrium.

|

Likely Pawtucket band of Massachusett artist, name once known, Naumkeag (now Salem, Mass.), 1500s. Basalt. H.4¾, W. 2½, D. 5 in. Gift of Miss Bessie Eaton, 1898 (E50296). Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by Jeffrey Dykes and Mark Sexton. (The Massachusett are the Indigenous Peoples from whom the state of Massachusetts took its name.) |

An Indigenous artist from the area around current-day Salem, Massachusetts, likely created this stylized sculpture of a black bear. The object can be seen as a representation of the interconnectedness between humans and the natural world and as an expression of a strong relationship with the land. This bear may have been created just decades before European settlers arrived in 1626 in the place we now call Salem and displaced the Pawtucket peoples already living there.

|

Valuables cabinet, James Symonds (1633–1714), Salem, Mass., 1679. Oak, maple, iron, and paint. H.16½, W 17, D. 9½ in. Museum purchase, made possible by anonymous donors, 2000 (138011). Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by Dennis Helmar. |

This cabinet is remarkable for its history of ownership, design, and survival. Salem’s premier seventeenth-century joiner James Symonds arranged the applied half-spindles, decorative moldings, and S-scrolls in orderly geometric patterns. These choices expressed a preference for the English design style known as Mannerism and reflect a transfer of European taste to an early American colonial settlement. The carved initials “JBP” commemorate the 1679 wedding of the cabinet’s first owners, Joseph and Bathsheba Pope, Quakers living in Salem Village, now Danvers, Massachusetts. The Popes gained notoriety thirteen years after their wedding, when their testimonies during the Salem witch trials led to the conviction and execution of three innocent people—Rebecca Nurse, Martha Cory, and John Proctor.

|

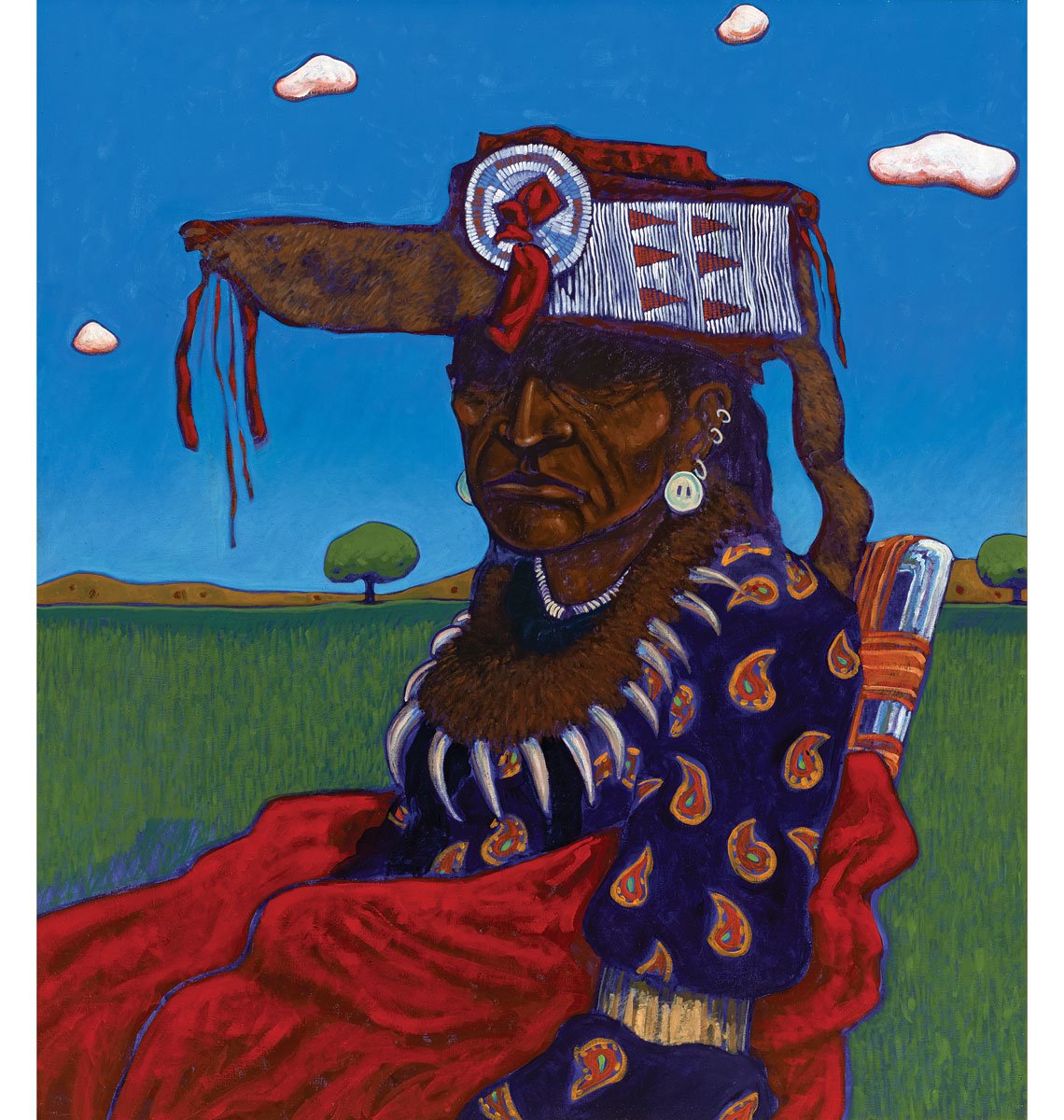

T. C. Cannon (Kiowa and Caddo, 1946–1978), Indian with Beaded Headdress, 1978. Oil on canvas, 52 x 46 inches. Museum purchase (2015.35.1). © The Estate of T. C. Cannon. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. |

T. C. Cannon is one of the most inventive Native artists in America. Witty, thoughtful, and sensitive, Cannon came of age in the socially and politically turbulent 1960s and 1970s. Cannon liberated his figures from the romanticized past and created a new present and future for them. Mass media, pop culture, the art world, and film and fashion industries have misrepresented Native people for centuries. Instead, Cannon depicts his people on his own terms, disrupting outdated, oversimplified portrayals. Cannon contrasts the elder warrior in traditional regalia with the modern aluminum folding lawn chair in which he sits, waiting for his dance at a pow wow. The mood Cannon captures in his expression and posture reads like a nineteenth-century photograph except for his seat and the vivid palette of his Southern Straight dance ensemble, the bright sky, and smudgy green grass. In Cannon’s expression, time is not always linear but cyclical. Through dance and song, he sees ancestral ties renewed, affirming that the past is always present.

|

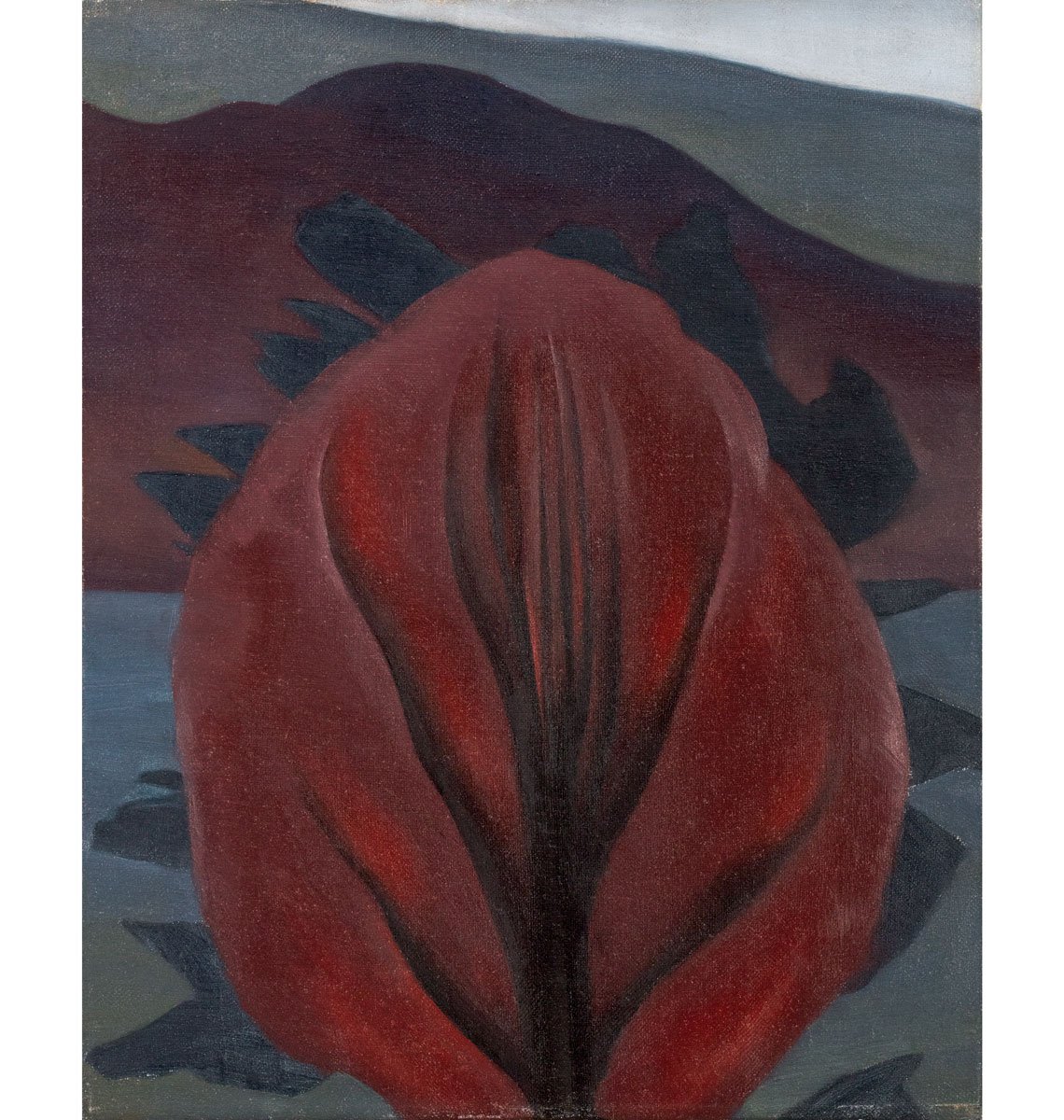

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Cedar and Red Maple, Lake George, 1921. Oil on canvas, 18 x 14⅝ inches. Gift of Peter S. Lynch in memory of Carolyn A. Lynch (2018.72.3). Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. ©2021 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

"I wish you could see the place here—there is something so perfect about the mountains and the lake and the trees—Sometimes I want to tear it all to pieces—it seems so perfect—but it is really lovely."

— Georgia O’Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe spent the summers from 1918–1934 in Lake George, New York, at the family home of her husband and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz. Lake George was a place of deep inspiration for her. She often stayed on into the fall, painting the seasonal color shifts around the lake and reveling in the quiet after the summer tourists and the extended Stieglitz family had left. Her treatment of natural forms and unconventional contours in this work demonstrate how she abstracted, combined, and layered the landscape in ways that were unprecedented in American art at that time.

|

Dressing chest, Thomas Seymour (1771–1848), carving attributed to Thomas Wightman (Active 1797–1817), about 1810. Mahogany, bird’s-eye maple, satinwood veneer, brass, and glass. H. 73½, W. 45, D. 25 in. Gift of Miriam and Francis Shaw Jr., 1935 (122350). Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. |

"The apartments are finished in as good order as any I have seen.

The furniture was rich but never violated the chastity of correct taste."

— Reverend William Bentley

Elizabeth Derby West was the independent-minded daughter of America’s first millionaire Elias Hasket Derby. She was one of the richest women in America when she divorced ship captain Nathaniel West in 1806, a rare occurrence during the period. Living in her Oak Hill mansion west of Salem, she commissioned the most luxurious furnishings and decorations in fashionable neoclassical style from the best craftsmen in Salem and Boston. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, elaborate dressing tables were popular with wealthy women in the new nation. Such tables symbolized civility and refinement, as well as intimacy, as the place where a woman prepares herself to face the world.

|

Hank Willis Thomas (b. 1976), Rich Black Specimen #460, 2017. Aluminum with powder coat and automotive paint, 75 x 47½ inches. Museum purchase, made possible by the Elizabeth Rogers Acquisition Fund (2019.23.1AB). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY. |

Hank Willis Thomas’ figure, ultrathin and larger than life, jumps from the archival pages into our sights. In the nineteenth century, stock books presented small printed imagery, or specimens, for sale to publishers for use in broadsides, pamphlets, and newspapers. Thomas based his sculpture on an image from an 1859 book, Specimens of Printing Types, recreating printing specimen number 460 of a “runaway slave.” A rainbow effect, that Thomas describes as “an aura or spiritual glow,” from the process of scanning the original book, highlights and animates the figure. Slipping through time, the figure forces us to reckon with his humanity and our own histories.

|

Sign from the first U.S. Custom House, Salem, Samuel McIntire (1757–1811), Salem, Mass., 1805. Wood, paint, pine wood, and gilding. H. 36, W. 115, D. 12 in. Gift of Joseph F. Tucker, 1907 (100754). Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by Jeffrey Dykes and Mark Sexton. |

All cargoes imported at Salem’s wharves in the nineteenth century were subject to the duties established by the US Customs Service. The government taxed many luxury commodities procured by local merchants from Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Europe. American maritime trade was so essential to the nation’s growing economy after the Revolutionary War that customs taxes accounted for nearly 90 percent of the federal budget. Samuel McIntire, Salem’s preeminent designer, architect, and cabinetmaker, carved this sign to adorn the newly built Salem Custom House at 6 Central Street. McIntire’s confident execution of the eagle with wings outspread and head actively turned mid-cry exemplifies his mastery of carved ornament. The eagle, holding a shield, bundle of arrows, and olive branch, signals the federal government’s presence in Salem.

|

PEM’s American art collection showcases creative expression in America spanning four centuries, telling rich stories of American life and the ongoing cultural exchange between the people of New England, the nation, and the wider world. The museum was among the first in the country to collect decorative arts, including finely crafted furniture, interior furnishings, and everyday objects that reflect the material culture of New England. In 2003 PEM was at the forefront of rethinking conventional installations of American art by integrating painting and sculpture with decorative arts in its new American art galleries.

Our forthcoming installation of Native American and American art explores vibrant expressions of what it means to belong and not belong—to a community, place, family, and nation. The United States, while founded on the notion of freedom, was realized through colonization and oppression. These brutal legacies continue to shape the nation’s laws, access to resources, and our sense of identity.

Distinct sections feature the strengths of each collection, but they also converge to explore certain themes in greater depth. Placing these collections on equal ground emphasizes that the American experience is unimaginable without the inclusion of Native American art, history, and culture.

Art has the power to transform how we think and see. The new installation of these collections will build upon this interdisciplinary approach, pushing further at efforts to draw out themes of American identity through diverse categories of objects. A chorus of voices—artists, poets, scholars, community members, and activists—demonstrate that multiple truths can coexist and that what we don’t see in a work of art is sometimes just as important as what we do see.

By rethinking America’s histories, how might we envision a better future together?

Karen Kramer, curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture, and Sarah Chasse, associate curator, co-curated the installation with support from assistant curator Lan Morgan.

This article was originally published in the 22nd Anniversary/Winter 2022 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|