American Modernist Design

|

Gilbert Rohde Paldao Group “Model 4105” Sideboard for Herman Miller, c. 1940. Image courtesy of Lobel Modern. |

|

by Benjamin Genocchio

| |

Original 1930 Monumental Skyscraper Vanity by Paul T. Frankl. This skyscraper vanity retains its brilliant untouched original lacquer, original stainless steel trim, original nickel plated brass pulls and “SKYSCRAPER FURNITURE Frankl Galleries” metal tag on the verso. With few floor model exceptions, these early Frankl studio pieces were custom made to order and are extremely rare. Only his early pieces bear the Frankl Galleries metal tag. Image courtesy of TFTM. |

American Modernism emerged in the second decade of the twentieth century to become the first uniquely American design aesthetic. “Interior designers I’ve spoken to feel that having something of original American Modernist Design in a project really sets it apart. I think that having an interest in and an understanding of American Modernist Design is very important,” says Maddie Sadofski of TFTM Gallery on Melrose Ave in Los Angeles. “When people see the finely curated displays of American Modernist furniture and the period objects in museums, it generates an interest in the history of American Modernism.

Even though American Modernist Design is nearing 100 years old, there are still many great examples by a raft of period designers to be found on the market, according to Sadofski. “The condition is critical and rare items in fine or prime condition by the important American Modernist designers are in demand by collectors,” she says. In addition, museums like MOMA, LACMA, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art are actively adding to their collections.

|

Kidney-shaped coffee table with lacquered cork top and canted mahogany slab legs by Paul T. Frankl for Johnson Furniture, photo courtesy Lobel Modern. |

| |

Donald Deskey burlwood chest of drawers designed for his own company AMODEC, (American Modern Decoration Company) circa 1930s. Photo courtesy Lobel Modern. |

There is also a good price-to-value ratio in this area of the market for everyday people looking to decorate homes with beautiful things. “A lot of people can’t afford high-end design by artisans who were making one-of-a-kind art pieces for homes, something that you begin to see a lot more of in the later periods of American design,” says Evan Lobel of Lobel Modern in New York. “The price point on American Modernist material can be favorable and you are buying a historical piece that is also beautifully made.”

Today, the pioneer designers that built a unique American modern design aesthetic are in most cases no longer household names, but their vision transformed American life completely. No other generation of designers before or since can make such a claim. Initially, they met resistance and prejudice. American tastes remained immutably conservative well into the 20th century, especially in the design field where traditional Early American dark wooden furniture dominated decorating schemes.

The taste situation was so dire that in 1925 the United States was invited to organize a presentation of national craftsmen and manufacturers for the prestigious Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs in Paris. The French had one clear stipulation — all participants must demonstrate “new inspiration and originality” and be reflective of “the modern decorative and industrial arts.” After extensive review it was determined the Americans must decline the invitation — no American modern design could be found.

|

Pair of lounge chairs designed by Donald Deskey for Radio City Music Hall, NYC in 1932. Deskey was commissioned to oversee all aspects of the interior of Radio City Music Hall, and stated as his goal, “We hope to impress the customers by sheer elegance, not by overwhelming them with ornament.” Recovered in vintage light sand-colored leather with mahogany detailing, from TFTM. |

|

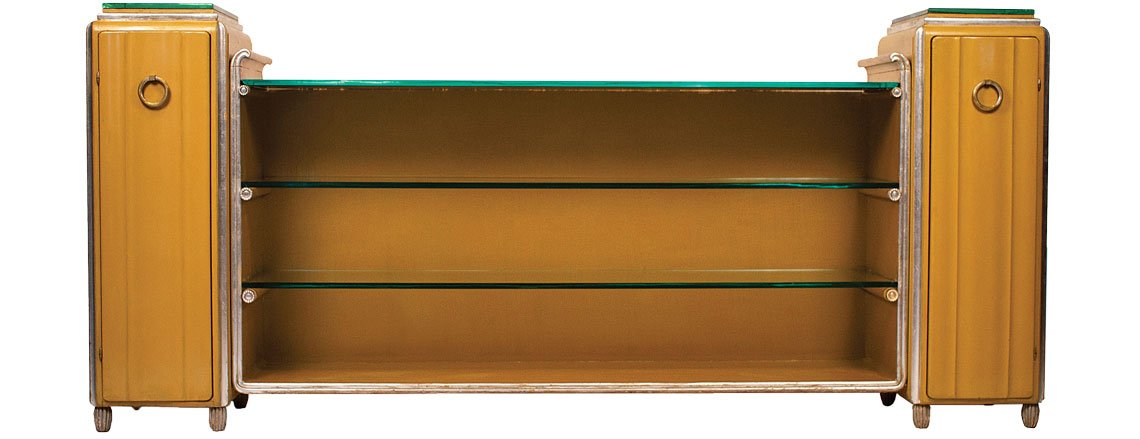

Paul T. Frankl Skyscraper Sideboard for Frankl Galleries NY, circa 1928. Rare and important lacquered sideboard in two-tone yellow ochre finish with silver leaf ornamentation, original mirrored tops, glass shelves, bullet hinges, faceted solid brass silver leafed hardware and silver plated shelf ornamentation. This cabinet was produced in Frankl’s workshop and sold through his gallery on 48th Street in New York. One of the earliest examples of American Modernism in all original condition. From 20cdesign. |

| |

Paul T. Frankl “Cloud” coffee tables in natural cork and bleached mahogany for Johnson Furniture Company, Model 5005, 1951. From 20cdesign. |

The story of how America rapidly, and brilliantly developed a modern design aesthetic in the two decades between World War I and World War II is a fascinating one. It is a story of influence, initially, with Americans borrowing from modern design movements in France, and later Germany and Scandinavia, beginning in the late 1920s with the French luxury style known as Art Deco, an abbreviation for Arts Décoratifs, which placed an emphasis on ornamentation, expensive materials and fine craftsmanship.

Americans didn’t embrace French Art Deco. It was too ornate, too costly, essentially an elegant custom aesthetic aimed at the elite clientele who could afford it. The designs were frequently formal, not terribly practical or innovative, and based on a model of European neoclassicism. A new generation of designers was needed to create an iteration that Americans actually embraced, was affordable, and was aimed at a wider contemporary market of middle-class consumers following the huge expansion in home construction and ownership across America.

| |

Paul T. Frankl armchair in polished nickel and leather for Frankl Galleries NY, 1929. Early Machine Age Modernism at its finest. The chair is a rare example of modernist nickel-plated steel and leather furniture designed by Paul Frankl. From 20cdesign. |

German modernism, in particular the mechanistic and socially oriented vision of the Bauhaus school had a profound influence on American modern design: The Bauhaus aesthetic stressed the simple, functional, and practical with geometric forms and machine-made materials such as metal, glass, linoleum, and plastics, all of which appealed to American designers at a time when rapid industrialization and machine age manufacturing enabled objects to be mass produced for a consumer society. The left-leaning politics and core social mission of the Bauhaus, though, fell on deaf ears.

Some members of the new generation of modern American designers were American-born, but many were European immigrants, among them several key members of the German Bauhaus (including Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe) after the Nazis closed the Bauhaus’s Dresden design school in 1933. American-born or not, by the end of the 1930s a pioneering group of designers using new materials and new industrial technologies had developed an American modern design style that was a product of this cocktail of social, cultural, economic and political influences.

|

Paul T. Frankl custom dining table designed for a project in La Jolla, California circa 1930. Has two 24-inch leaves, when both are inserted the table measures 108 inches fully extended, comfortably seating 10 to 12. Lacquered wood and cork base, silvered glass. From Converso. |

| |

Rare custom bookcase by Paul T. Frankl, c. 1930. Bookcase/ storage cabinet of orange and black lacquered wood with gold painted face in a snaking geometric motif and thick glass side panels. A rare example that exemplifies Frankl’s departure from his skyscraper furniture into a more simplified direction. From Donzella, photo by Josh Gaddy. |

The list of designers who contributed to the emergence of a uniquely American design aesthetic is long and varied, for American society in all areas — commercial, industrial, domestic — underwent a profound change in the decades between the Wars. These designers included Paul T. Frankl, Raymond Loewy, Donald Deskey, Kem Weber, Jock Peters, Gilbert Rohde, Norman Bel Geddes, Russel Wright, Walter Dorwin Teague, Walter Von Nessen, Warren McArthur and Henry Dreyfuss.

“There are really two facets of unique American modernist design,” says Sadofski. “These styles are Skyscraper design and Streamline Moderne design.” Skyscraper-style furniture and objects originated in the mid-1920s and Streamline Moderne originated in the 1930s. Paul Frankl, the central creator of Skyscraper design, was influenced by the buildings in New York City including examples of Art Deco architecture like the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center, which he considered iconic symbols of modern American genius and modernity.

Frankl took his initial formal inspiration from French Art Deco and the idea of quality materials and craftsmanship. “He rejected the idea that modern furniture should be standardized and mass-produced,” Sadofski says, “instead, he promoted individual craftsmanship”. Pieces were produced in workshops and in editions but were all hand finished. His hardware, especially his pulls made of cast metal, are almost like pieces of jewelry. His designs often stress geometry and monumentality.

|

Rare desk and chair designed by Donald Deskey and produced by Ypsilanti Reed Furniture Corp. Walnut top and drawer boxes with copper-plated steel supports and details. A very rare set that perfectly represents Deskey’s design aesthetic from the early 1930s. From Donzella, photo by Josh Gaddy. |

TFTM Gallery has an original 1930 “Monumental Skyscraper Vanity” by Frankl that is so architectural it looks like a model of an industrial complex. “It is a masterpiece of the genre,” Sadofski says, pointing out that the piece retains all of its untouched original bright red lacquer, original stainless steel trim, nickel-plated brass pulls and the Frankl Galleries metal tag as a guarantee of authenticity. “These early Frankl studio pieces were custom-made to order and extremely rare,” she says.

20cdesign in Dallas also has some extraordinary and rare Frankl furniture from the early years of American Art Deco modernism. “Frankl Skyscraper Sideboard” c.1928 is an early, spectacular example of American modernism and in original condition. It was likely produced at his shop in New York and, as Ryan Rucker from the gallery points out, retains “all original mirrored tops, glass shelves, bullet hinges, faceted solid brass silver leafed hardware and silver plated shelf ornamentation.” It is an outstanding period piece that reflects the style, ambition and lifestyle of the time.

|  | |

| Left: Warren McArthur “The Chairman” style no. 1081, round lounge chair in anodized aluminum and leather. Manufactured at his factory in Connecticut circa 1936. From Appleton. Right: This iconic original “Airline” armchair was designed by KEM (Karl Emanuel Martin) Weber in 1934 and produced in a limited run of 300 in 1938 for the offices at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. The design is adapted from cantilevered chair designs by Marcel Breuer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The Airline Chair’s streamlined design is a quintessential expression of Modernism and the Machine Age. Photo courtesy Peter Blake Gallery. | ||

| |

White cork top walnut side table, Model 5026 by Paul T. Frankl circa 1948, from Glen Leroux Antiques. |

Converso, based in Chicago, has a few marvelous Frankl pieces including a custom dining table, which Lawrence Converso, owner of the gallery says was “designed for a project in La Jolla, California, circa 1930.” It is made of red and black lacquered wood, has a cork base, along with silvered glass and retains a timeless simplified elegance. “People love the cork stuff now,” says Converso. “It used to be unpopular, for a long time, but now all the cork tables are doing well, are popular again,” he says. He notes the market for Frankl “Station Wagon” cabinets with leather handles is very strong. Several Incollect dealers have outstanding examples of these signature designs.

Frankl was born in Austria in 1887 and trained as an architect in Vienna and Berlin before emigrating to the United States. He was one of the most influential promoters of modern design styles in America and also helped to found the American Designers Gallery in New York alongside American-born Donald Deskey who studied design in Paris (he also attended the 1925 Paris Exposition) and in 1932, at age 38, completed a commission for the interiors of Radio City Music Hall — his tribute to American Art Deco and, today, a signature remaining example of this American design genre.

Deskey went on to have a formative influence on American industrial design, his design style and ideas evolving swiftly from Art Deco into the streamlined modernism of American design in the mid to late 1930s. Deskey is even quoted as saying, about his interior designs for the Radio City Music Hall, ”We hope to impress the customers by sheer elegance, not by overwhelming them with ornament”, signaling already his desire to move away from the more ornate decor and lavishness of French Art Deco.

|

Pair of Warren McArthur sling chaises/lounge chairs, style no. 1000. Anodized aluminum frame with cast rubber “doughnut” feet. Manufactured at his factory in Connecticut, circa 1938. From Appleton. |

|

Rare Warren McArthur curved Park Avenue Sofa with serpentine front, a derivation on his classic Park Avenue Couch, style no. 900 BAU. A custom order, possibly a unique piece. Anodized aluminum frame, mohair upholstery, circa 1936. From Appleton. |

Numerous Incollect dealers have wonderful examples of Deskey design material from all periods — his andirons are especially popular and perhaps his most recognizable design today. An example of his initial American Art Deco vision, at TFTM, is a pair of original club chairs and a pair of original lounge chairs that were designed for the Grand Lounge in the Radio City Music Hall interior in 1932. They are unique chairs, handmade, that have been fully restored and recovered in period-style material.

Deskey’s earliest modernist furniture was elegant, frequently in exotic woods or combining wood with metals, and was initially all custom-made. Today it is highly prized among design collectors. High Style Deco in New York is offering a stunning circa 1935 sideboard manufactured by Widdicomb Furniture Company. Richly rendered in Art Deco black lacquer, burled Carpathian elm and walnut, it is a warm, sensual, clean-lined work of design. The streamlined, semi-circular compartments on each side further underscore the aesthetic.

|

Elegant pair of walnut button-tufted slipper chairs by Gilbert Rohde for Herman Miller, circa 1940s. From FS20. |

| |

Rare Gilbert Rohde for Herman Miller cocktail table, circa 1939. Tapered spiked legs pass through glass with wood domed covered caps. From Converso. |

Several other Incollect dealers including Glen Leroux, Donzella and Lobel Modern have important early Deskey pieces for period collectors and anyone looking for exquisitely made and designed modernist furniture. Donzella has a rare desk and chair set made of copper-plated steel and walnut. Donzella believes these are a rare set that is possibly unique but likely custom variants of models produced by Ypsilanti Reed Furniture Corp. It embodies Deskey’s design style from the early 1930s.

American Streamline Moderne, the second facet of American modernist design, was inspired by aerodynamic design and streamlining taking hold in industrial design during the 1930s. Modern American Streamline design was used in buildings, cars, planes, ships and industrial products and often emphasized curved forms, horizontal lines, and nautical or aerodynamic elements. Household items such as appliances, lighting, and furniture were subsequently ‘streamlined’ according to new principles utilizing materials that were frequently mass manufactured and therefore more widely affordable.

|

Gilbert Rohde bow front cabinet /server, model 3723 for Herman Miller, 1937. Maidou burl door fronts, mahogany top and sides, and rosewood base. From Collage 20th Century Classics. |

Machine age industrial designers Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes and Henry Dreyfuss are today closely associated with this movement, as is Warren McArthur, a designer for commercial and residential products who, following graduation from Cornell University with a degree in engineering in 1906, began designing and making, first in Los Angeles, then Rome, N.Y. and later Bantam, Conn., aluminum tubular metal chairs, tables, sofas, lanterns and lamps for homes, train seating and military and civilian aircraft. He is popularly known as the father of the modern aircraft seat.

McArthur’s furniture was hand produced and finished, so buyers could get anything they wanted as far as scale, shape or color. “The structure is the decoration with Warren’s furniture,” says Nick Brown, owner of Appleton in Maine, referring to the way metal joinery was made a decorative feature of his designs. “As an inventor, he had several patents for a unique assembly process that combined first steel tube then very soon after aluminum tube with standardized parts for joinery and an internally threaded rod to create a compression assembly to hold it all together,” Brown says.

|

|

A set of six dining chairs by Gilbert Rohde for Herman Miller. Model 3966, originally designed in 1939, in solid birchwood with original upholstery, from Converso. |

Appleton in Maine, Objects 20c from West Palm Beach, Converso and Lobel Modern in New York have signature early examples of McArthur’s innovative designs using tube metal. Appleton has a set of “Spoon Back” dining chairs, produced in the early 1930s, and made after he opened his first shop in June of 1930 in Los Angeles. The designs were an instant success, Brown says. “This use of a new material, aluminum tubing for the building of lightweight furniture, with flexible framing, while offering a rainbow of colors and the durability of the anodic coating caught the eye of architects, hoteliers, designers, and leading figures of the social, entertainment, and financial worlds almost immediately when he opened his first shop.”

| |

Gilbert Rohde Paldao Group occasional table, model 4187 for Herman Miller. Biomorphic-shaped top of bookmatched acacia veneer on tapered leatherette-wrapped legs. Rohde’s association with Herman Miller Furniture company, a collaborative relationship whose significance proved to be historic, began in 1932. The success of Rohde’s designs for Herman Miller, many of which remained in production for five to ten years, demonstrated that mass production had the potential to spread modernism. From Albert Joseph Galley, The Galleries at 200 LEX powered by Incollect. |

Part of the allure was the unique, distinctive matte silver finish. “McArthur references the soft brilliance of old polished silver as his inspiration for the surface finish of his anodized aluminum tubing,” Brown explains, “in contrast to the mirror hardness of nickel/chrome plating popular with the Bauhaus crowd and their American followers. In keeping with this old silver theme, the earliest of his aluminum joineries are not ribbed or smooth walled but resemble a traditional napkin ring with flared ends.”

Brown has specialized in McArthur’s furniture since the mid-1980s and is an expert in the area. He recently reviewed various sites that offer Warren McArthur and, he says, “a lot has changed hands.” But he still feels McArthur has never really received full recognition for his designs. “McArthur was the Cadillac/Rolls Royce of US Aircraft seating and his significance in that arena can not be overstated,” Brown says, adding his designs for aircraft seating were used by the US Airforce and helped win WWII.

Converso has a pair of McArthur’s signature sofas, Model 915, made of anodized aluminum, with machine-pressed aluminum fittings that have been reupholstered with a new cotton-linen fabric. Dating from the period 1920–1949, they are one of several classic pieces by McArthur Converso has handled. “He made really spectacular stuff,” Lawrence Converso says. ‘If people knew how sturdy it is and how light it is, it would be a revelation.” Converso had a set of ten dining chairs that he just sold to a collector in London. “These are special pieces, and those are always desirable.”

| |

An original 1927 Arizona Biltmore Chair designed by KEM Weber for the luxurious Arizona Biltmore Hotel, Phoenix, dubbed “The Jewel of the Desert.” Detailed inlaid accent striping in the wood runs along the top, sides and front of the chair frame. From TFTM. |

“The whole early modernist design movement was a moment, an interesting moment in American history,” Converso says, adding that there are still many great examples by period designers to be found on the market. Glen Leroux Antiques, in Westport, Conn., has an iconic Gilbert Rohde streamline sideboard from 1936, with a stepped-up top, burled doors, circular cut-out and brushed steel pulls. TFTM has cabinets by Gilbert Rohde for Herman Miller, including a Streamline Art Deco cabinet from 1933, as well as an iconic airline chair designed by Kem Weber for Disney Studios and a black lacquered sideboard by Walter Dorwin Teague with streamline style hardware.

Lobel considers Rohde the most successful and aesthetically pleasing designer of the period. “His pieces are subdued enough they can be worked into any interior,” he says. “I’ve sold quite a few and currently have some more.” Rohde popularized the use of Lucite, using it specifically for cabinet pulls which, for Lobel, makes him modern but also contemporary and therefore relevant to current interior designers. “Lucite is still considered a cool material and the idea that Rohde was using it in the 1930s and 40s shows how forward-thinking he was.”

Jake Baer, CEO of Newel in New York, agrees with Lobel about the forward-thinking nature of American modernist design. “This stuff was completely new, nobody had seen anything like it,” he says. “The design was so ahead of its time, even today is ahead of its time, for it was truly innovative.” Baer is increasingly approached to loan signature modernist American furniture for movie and television shows, especially anything set in the future. “The fact they want to use design from the 1930s and 1940s proves to me it has this constant lasting appeal.”

|

Game table with a clover-shaped bleached rosewood top resting on four cylindrical walnut legs by Edward J. Wormley for Dunbar Furniture Company, from Newel. |

Baer has witnessed renewed market interest, he says, in designers from this period, especially among young people. “This is one of our stronger categories because it has these futuristic vibes to it. Young people want to live in the future and a lot of the designs stay true to that look, being forward-looking and futuristic — they make their own rules, blending together ideas of the future, technology and art.” A very American Modernist point of view, indeed.