Winterthur Primer: The Byrdcliffe Library

In 1902, long before the hippies came to town, Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead (1854-1929), along with his wife, Jane Byrd McCall Whitehead, artist Bolton Brown, and writer Hervey White, founded the Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts community outside Woodstock, New York. Inspired by his teacher, John Ruskin, and the writings of William Morris, Whitehead was dismayed by the bitter fruits of industrialization: social and economic inequality, terrible working conditions, and especially the rise of machine technology that reduced skilled artisans to drudgery. To combat these developments, Whitehead built houses, workshops, studios, and community spaces on Mount Guardian, just outside Woodstock, in the picturesque Hudson River Valley, where artisans and craftspeople could produce furniture, metalwork, pottery, and art works. As artists, designers, and intellectuals, such as Hermann Dudley Murphy, Birge Harrison, Zulma Steele, Edna Walker, John Duncan, Ellen Gates Starr, Jane Addams, Giovanni Troccoli, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, John Burroughs, and Edith Wherry came to Byrdcliffe, it became one of America’s foremost artistic and intellectual communities in the first decades of the twentieth century.

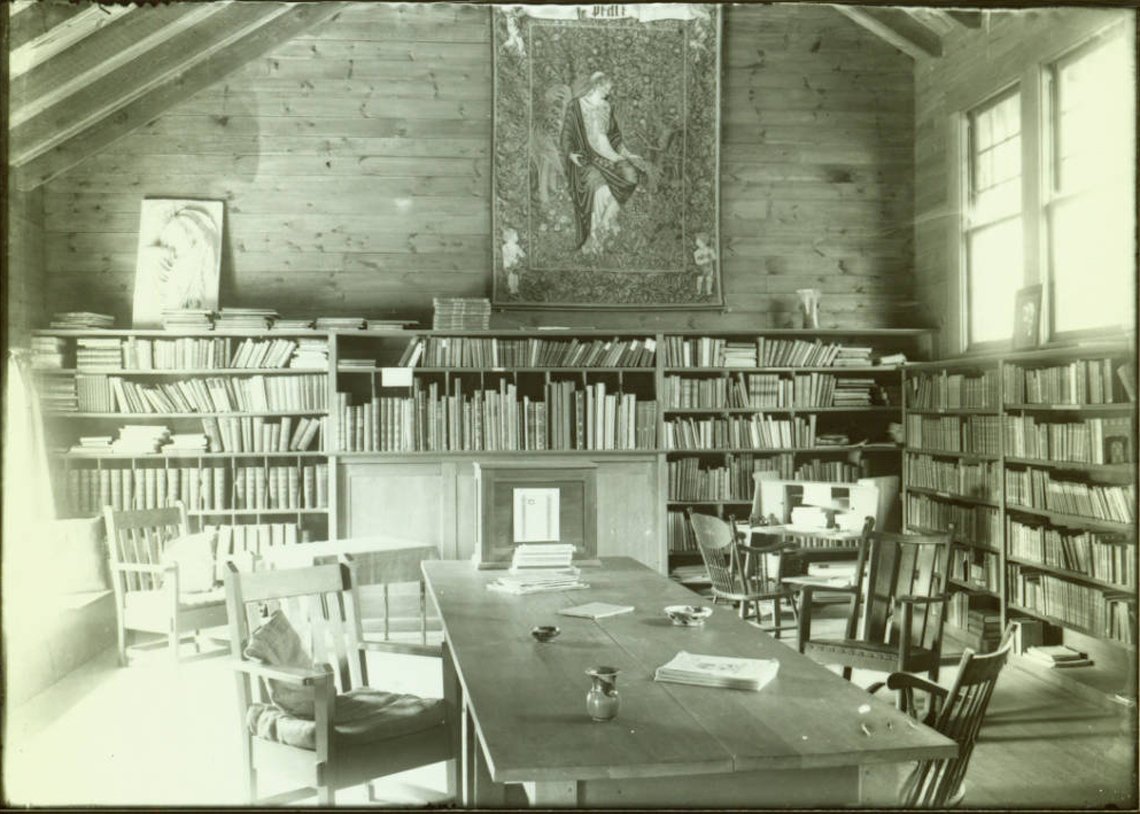

A centerpiece of Byrdcliffe was its library (Fig. 1), which contained nearly five thousand volumes. Located in Byrdcliffe’s large main studio building used for artists and exhibition of community-produced works, the room was decorated with Whitehead’s personal collection of sculpture, tapestries, pottery, and fine art dating back to his days studying under John Ruskin at Oxford. The shelves were stocked with Whitehead’s collection of volumes by Homer, Cicero, Virgil, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, G.W.F. Hegel, Rudyard Kipling, Dante Gabriel Rosetti, Oscar Wilde, John Ruskin, and Kelmscott Press editions of William Morris—a well-rounded library of a person of means.

|

Fig. 1: Interior of library. A William Morris tapestry is over the shelves at far end of the room. A long library table with chairs and at the end sits the wooden Byrdcliffe card catalogue. Modern print from glass plate negative. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library (Collection 209, 92x39.1140.11c). |

|

Fig. 2: Colored drawing of a tulip dining table, #64, (dimensions of top given); on back: #64, oak dining table, chestnut design [although in fact the drawing shows tulip poplar flowers and leaves], $120. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library (Collection 209, 02x170.44). |

| |

Fig. 3: Byrdcliffe Library Card Catalog and catalog Cards. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library (Collection 209). Photo by Jim Schneck. |

Visiting Byrdcliffe in 1905, naturalist John Burroughs commented, “The large solid library was a surprise to me. Few colleges have as good.” One person who especially enjoyed the library was Annie Thompson, sister of metalworker Bertha Thompson, who remembered Whitehead’s vast array of Italian, French, and German books. “There was no librarian—we just signed in and out or read them [the books] in the comfortable room.”

The community was plagued by poor sales and interest in the community waned in the years leading up to World War I. Byrdcliffe became more of a summer retreat, though it never relinquished its artistic mission and still hosts a robust artist-in-residency program today. Much of Byrdcliffe’s material left Mount Guardian, notably in 1991, when a descendant of the Whiteheads gifted the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library the vast majority of the community’s manuscript collection, including letters, periodicals, photographs, maps, and design material from the community’s studios and workshop (Fig. 2). In addition, Winterthur obtained select pieces of furniture as well as remnants of Whitehead’s library, including the Byrdcliffe book ledger, where each book was meticulously catalogued, as well as the cards and physical card catalogue, adorned with the signature symbol of Byrdcliffe, the Fleur de Lys (Fig. 3). As scholars and collectors continue to covet the fruits of this art colony, and look for inspiration from the Arts and Crafts Movement, Winterthur has become an important repository of information about America’s talented craftspeople, artists, and dreamers who gathered at Byrdcliffe.

Thomas A. Guiler is Assistant Professor of History and Public Humanities, Academic Programs, at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

This article was originally published in the 2019 Anniversary/Spring issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com.

1. For more information on Byrdcliffe, see Nancy E. Green, Byrdcliffe: An American Arts and Crafts Colony, ed. Nancy E. Green (Ithaca, NY: Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, 2004).

2. Alvan F. Sanborn, “Leaders in American Arts and Crafts,” Good Housekeeping, February 1907, 147-148; Byrdcliffe Library Card Catalog and catalog Cards: Location: 41 D 3 and 4, Series XI, Collection 209 (Byrdcliffe), Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera; Lucy Brown, “My First Summer In Woodstock,” in Woodstock Years: Publications of the Woodstock Historical Society, ed. Richard R. Heppner (Woodstock, NY: The Historical Society of Woodstock), 44; Bertha Thompson, “The Craftsmen of Byrdcliffe,” Publications of the Woodstock Historical Society. July 1933, 8.

3. Letter from John Burroughs August 30, 1905 Collection 209 (Byrdcliffe), Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

4. Annie Thompson, “Bertha and Byrdcliffe,” 6-8, Thompson Family Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.