-

FINE ART

-

FURNITURE & LIGHTING

-

NEW + CUSTOM

- Featured Bespoke Articles

- Hélène de Saint Lager’s Designs…

- Amorph-Where wood comes to life

- Markus Haase: Translating Artistic...

- Trent Jansen: Design Meets Heritage

- Hoon Moreau: Sculptural Poetry

- Kam Tin: The Art of Modern Baroque Furniture

- Gregory Nangle and Outcast Studios

- Roman Plyus Designs Furniture That’s…

- Ervan Boulloud: Daring Ingenuity

- Julian Mayor: Mirror Image

-

DECORATIVE ARTS

- JEWELRY

-

INTERIORS

- Featured Projects

- East Shore, Seattle, Washington by Kylee Shintaffer Design

- Apartment in Claudio Coello, Madrid by L.A. Studio Interiorismo

- The Apthorp by 2Michaels

- Houston Mid-Century by Jamie Bush + Co.

- Sag Harbor by David Scott

- Park Avenue Aerie by William McIntosh Design

- Sculptural Modern by Kendell Wilkinson Design

- Noho Loft by Frampton Co

- Greenwich, CT by Mark Cunningham Inc

- West End Avenue by Mendelson Group

- Interior Design Books You Need to Know

- Distinctly American: Houses and Interiors by Hendricks Churchill and A Mood, A Thought, A Feeling: Interiors by Young Huh

- Robert Stilin: New Work, The Refined Home: Sheldon Harte and Inside Palm Springs

- Torrey: Private Spaces: Great American Design and Marshall Watson’s Defining Elegance

- Ashe Leandro: Architecture + Interiors, David Kleinberg: Interiors, and The Living Room from The Design Leadership Network

- Cullman & Kravis: Interiors, Nicole Hollis: Artistry of Home, and Michael S. Smith, Classic by Design

- New books by Alyssa Kapito, Rees Roberts + Partners, Gil Schafer, and Bunny Williams: Life in the Garden

- Peter Pennoyer Architects: City | Country and Jed Johnson: Opulent Restraint

- The Elegant Life by Alex Papachristidis and More is More Is More: Today’s Maximalist Interiors by Carl Dellatore

- Extraordinary Interiors by Suzanne Tucker and Destinations by Jean-Louis Deniot

- Shelf Love: The Year's Top New Design Books

-

MAGAZINE

- Featured Articles

- Northern Lights: Lighting the Scandinavian Way

- Milo Baughman: The Father of California Modern Design

- A Chandelier of Rare Provenance

- The Evergreen Allure of Gustavian Style

- Every Picture Tells a Story: Fine Art Photography

- Vive La France: Mid-Century French Design

- The Timeless Elegance of Barovier & Toso

- Paavo Tynell: The Art of Radical Simplicity

- The Magic of Mid-Century American Design

- Max Ingrand: The Power of Light and Control

- The Maverick Genius of Philip & Kelvin LaVerne

- 10 Pioneers of Modern Scandinavian Design

- The Untamed Genius of Paul Evans

- Pablo Picasso’s Enduring Legacy

- Karl Springer: Maximalist Minimalism

- See all Articles

Period

Location

Size

- Clear All

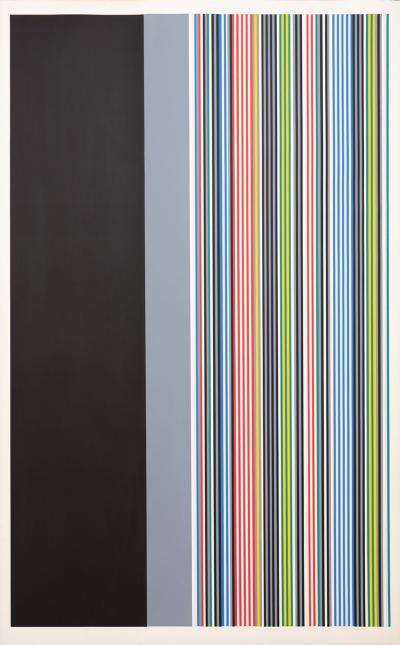

Gene Davis

American, 1920 - 1985

Gene Davis was an American abstract painter. Best known for his use of multicolored vertical stripes throughout his body of work, Davis was a major contributor in the Color Field and Post-Painterly Abstraction movements, and prominent figure of the Washington Color School.

Davis considered his nonacademic background a blessing that freed him from the limitations of a traditional art school orientation. His early paintings and drawings—though they show the influence of such artists as the Swiss painter Paul Klee and the American abstractionist Arshile Gorky—display a distinct improvisational quality. This same preference for spontaneity characterizes Davis's selection of color in his later stripe paintings. Despite their calculated appearance, Davis's stripe works were not based on conscious use of theories or formulas. Davis often compared himself to a jazz musician who plays by ear, describing his approach to painting as 'playing by eye.'

In the 1960s, art critics identified Davis as a leader of the Washington Color School, a loosely connected group of Washington painters who created abstract compositions in acrylic colors on unprimed canvas. Their work exemplified what the critic Barbara Rose defined as the 'primacy of color' in abstract painting. And while he took up abstract painting in the 1940s as a hobby, and was featured in a few local shows, he was never successful enough to devote his full time to art until, after 35 years in journalism, he finally turned to it 1968. “The idea of my ever making a livelihood out of painting was the farthest thing from my mind,” he said in a 1981 interview. But he hit on something—a parade of brightly-colored, edge-to-edge stripes—that not only made his name and changed his career, it put him at the forefront at the only major art movement to emanate from the nation’s capital, the Washington Color School.

In contrast, Davis experimented with complex schemes that lend themselves to sustained periods of viewing. Davis suggested that "instead of simply glancing at the work, select a specific color and take the time to see how it operates across the painting." In discussing his stripe work, Davis spoke not simply about the importance of color, but about 'color interval:' the rhythmic, almost musical, effects caused by the irregular appearance of colors or shades within a composition.Davis is known primarily for the stripe works that span twenty-seven years, but he was a versatile artist who worked in a variety of formats and media

In keeping with his unorthodox attitudes, Davis's works do not follow in an orderly sequence. Davis described his method as "a tendency to raid my past without guilt [by] going back and picking up on some idea that I flirted with briefly, say fifteen or twenty years ago. I will then take this idea and explore it more in depth, almost as if no time had elapsed between the present and the time of its original conception." As a result, similar works may be separated by years or even decades. … Davis's works, which resonate with his romantic, free-wheeling approach to art-making, reveal a seriousness balanced by whimsy and an unpredictability that is always a source of joy.

In 1972 Davis created Franklin's Footpath, which was at the time the world's largest artwork, by painting colorful stripes on the street in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the world's largest painting, Niagara (43,680 square feet), in a parking lot in Lewiston, NY. His "micro-paintings", at the other extreme, were as small as 3/8 of an inch square.

A lifelong Washington, D.C. resident, Davis died in his hometown on April 6, 1985, and his work is included among the collections of important institutions such as the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Davis considered his nonacademic background a blessing that freed him from the limitations of a traditional art school orientation. His early paintings and drawings—though they show the influence of such artists as the Swiss painter Paul Klee and the American abstractionist Arshile Gorky—display a distinct improvisational quality. This same preference for spontaneity characterizes Davis's selection of color in his later stripe paintings. Despite their calculated appearance, Davis's stripe works were not based on conscious use of theories or formulas. Davis often compared himself to a jazz musician who plays by ear, describing his approach to painting as 'playing by eye.'

In the 1960s, art critics identified Davis as a leader of the Washington Color School, a loosely connected group of Washington painters who created abstract compositions in acrylic colors on unprimed canvas. Their work exemplified what the critic Barbara Rose defined as the 'primacy of color' in abstract painting. And while he took up abstract painting in the 1940s as a hobby, and was featured in a few local shows, he was never successful enough to devote his full time to art until, after 35 years in journalism, he finally turned to it 1968. “The idea of my ever making a livelihood out of painting was the farthest thing from my mind,” he said in a 1981 interview. But he hit on something—a parade of brightly-colored, edge-to-edge stripes—that not only made his name and changed his career, it put him at the forefront at the only major art movement to emanate from the nation’s capital, the Washington Color School.

In contrast, Davis experimented with complex schemes that lend themselves to sustained periods of viewing. Davis suggested that "instead of simply glancing at the work, select a specific color and take the time to see how it operates across the painting." In discussing his stripe work, Davis spoke not simply about the importance of color, but about 'color interval:' the rhythmic, almost musical, effects caused by the irregular appearance of colors or shades within a composition.Davis is known primarily for the stripe works that span twenty-seven years, but he was a versatile artist who worked in a variety of formats and media

In keeping with his unorthodox attitudes, Davis's works do not follow in an orderly sequence. Davis described his method as "a tendency to raid my past without guilt [by] going back and picking up on some idea that I flirted with briefly, say fifteen or twenty years ago. I will then take this idea and explore it more in depth, almost as if no time had elapsed between the present and the time of its original conception." As a result, similar works may be separated by years or even decades. … Davis's works, which resonate with his romantic, free-wheeling approach to art-making, reveal a seriousness balanced by whimsy and an unpredictability that is always a source of joy.

In 1972 Davis created Franklin's Footpath, which was at the time the world's largest artwork, by painting colorful stripes on the street in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the world's largest painting, Niagara (43,680 square feet), in a parking lot in Lewiston, NY. His "micro-paintings", at the other extreme, were as small as 3/8 of an inch square.

A lifelong Washington, D.C. resident, Davis died in his hometown on April 6, 1985, and his work is included among the collections of important institutions such as the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Gene Davis

Gene Davis Signed and Numbered Limited Edition Color Field Serigraph 1974

H 75 in W 48 in D 2 in

$ 8,000

Loading...

Loading...