Housing Our History: A Celebration of Place, Past & Community

It’s been more than a decade since Richard Moe, president emeritus of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, raised the question: Are there too many house museums? 1 Since then, the discussion has remained on the museum field’s radar, and there is a conviction among many directors and curators that an estimated 7,000–9,000 house museums and historical societies nationwide are too numerous and too alike, and that insufficient funds put the buildings at risk and that the formula is unsustainable.2 And really, who needs another tutorial on rope beds and pre-industrial cooking? So when the National Trust and the American Association for State & Local History (AASLH) met, in conjunction with museum leaders and preservationists, at the Rockefeller Estate, Kykuit, in Westchester County, New York, in 2007 they launched an initiative aimed at transitioning house museums deemed unsustainable to other uses; the discussion is ongoing.3

In some cases such an initiative is sensible and necessary, but what’s missing is the message that the best house museums and community-based historical organizations preserve and present unique aspects of the American experience and are a refuge for local knowledge at a time when homogenization is destroying our sense of place and weakening civic attachment. Repositories of localism, they are in fact different, one to the next, and often do what they do with frugality and a heavy reliance on volunteers. What is not to love? As a colleague recently put it, “Historic houses are where the rubber meets the road—where kids find history can be real.” It’s also where communities keep their memories and past accomplishments alive and preserve their local wisdom and sense of place. Art, artifacts, archives, and antiques serving the needs of community are the antithesis of “art for art’s sake.”

Whether or not some of these house museums and local historical organizations face issues of sustainability—our American culture and civilization faces something worse without them. They are indispensible beacons of joy and civic reflection. Yes, most of them contain similar kinds of things—pottery, furniture, costumes, portraits, photographs, maps, and the products of home industries. But having local versions—local photographs, local architecture, and things made by local hands—in a global economy, where almost nothing we use is locally made or grown, makes the difference. The totality of all this local history and cultural material is as dazzling and multidimensional as our diverse nation. It is history made personal and accessible.

Half of our nation’s cultural patrimony is housed in small to mid-size community-based museums. How is that possible? Because they outnumber big museums by approximately 20:1. And, while doing that, are also sparing historic buildings from demolition or remodeling.

Our best house museums and community-based historical organizations are outposts of authenticity in a world increasingly blanketed in sameness. The problem is not that we have too many house museums, it’s that foundations, granting agencies, and even our partners in historic preservation inadvertently overlook the needs of small to mid-sized organizations and museums. Raising the bar of support is not only the least we as preservationists can do, it’s the best we can do.

The last half of the nineteenth century saw the birth of the heritage industry, when this country’s first house museums and historical societies were founded. In 1870, a decade after the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association was established to preserve George Washington’s estate, George Sheldon, heralded as the “Historian of the First Frontier,” founded the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association (PVMA) in one of the most historicized towns in New England, Deerfield, Massachusetts. One of the first regional history museums in America, PVMA was housed in the 1799 Deerfield Academy building, art and artifacts from local families—including dozens of masterpieces of furniture and what is now one of the best collections of Arts & Crafts movement work from any locale in the country, as well as archives and rare books of remarkable depth and variety—have been on display.4

Some of our first and most successful house museums belonged to famous occupants. George Washington’s Mount Vernon, in Fairfax County, Virginia, our first house museum, sets the gold standard for impeccably restored and interpreted historic houses. Others followed, among them President Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage in Davidson County, Tennessee; Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Fig. 1) in Charlottesville, Virginia; the Mark Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut; Frederic Church’s Olana in Hudson, New York. Houses like William Randolph Hearst’s “Castle,” in San Simeon, California; William Clay Frick’s Clayton, in Pittsburgh; George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore, in Asheville, North Carolina; and the Newport mansions speak more to class than community, many containing furnishings and art to rival any art museum. Indeed the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston is in essence a glorified house museum, as is the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, and the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California.

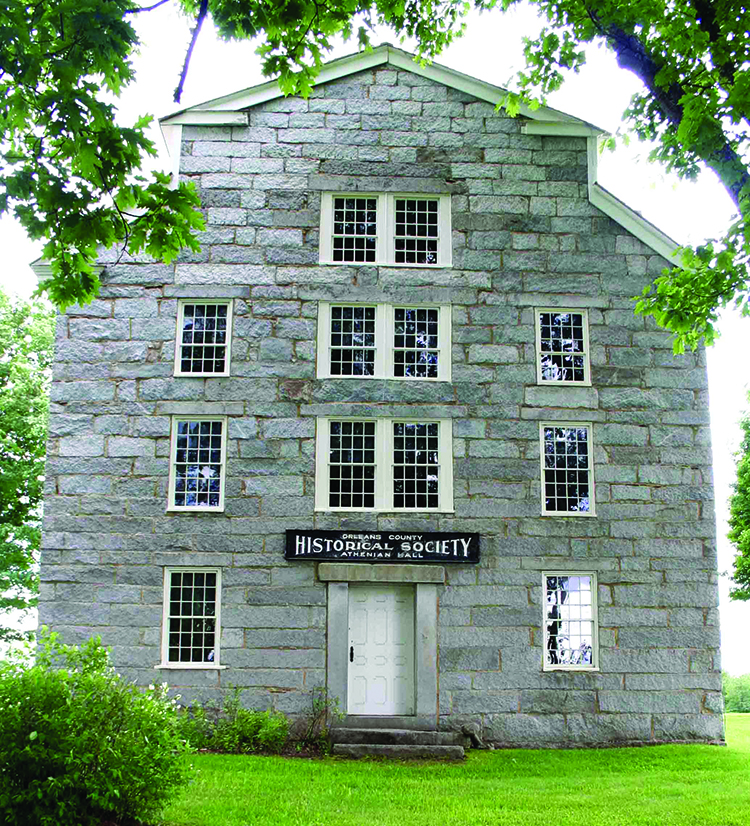

Many house museums did not belong to people of great wealth or national fame. They are simply the repositories of the stuff and stories of their communities. These collections are often maintained on a shoestring. One of my favorites is the Orleans County Historical Society (Fig. 2), aka the Old Stone House Museum in Brownington, Vermont. Housed in the 1835 Athenian Hall, originally a dormitory for the Orleans County Grammar School, it was built in 1829 by African-American Reverend Alexander Twilight (1795–1857), the school’s teacher. Its contents include local folk art, furniture, and paintings, while special subject galleries interpret a student’s room, Native American artifacts, the former Grand Army of the Republic collection, and the scientific equipment, teaching aids, and artifacts associated with Rev. Twilight. The Society operates several buildings within walking distance, giving the rural village the effect of a museum-without-walls. Adult courses, public programs, an array of youth education programs, special services for home-schoolers, and wedding facilities, make this treasure trove a model cultural organization serving a rural area.

Family-formed, document-rich houses are the best way to teach history—intimate, personal, close at hand, and authentic. Unadulterated and largely untouched by curatorial hands, they are material culture in a nutshell and as archeological as anything found underground. It used to be somewhat common for families to hold onto houses for generations. Today, when most people don’t know the names of their own great-grandparents, in these time capsules we can contemplate lives deeply infused with multigenerational continuity.

Hartford, Connecticut’s, Butler-McCook House (Fig. 3) was built in 1782, but contains items brought there from the seventeenth-century Butler Tavern further up on Main Street. When the tavern was demolished in the 1850s, the family salvaged its original staircase, stashing it away in the basement. The McCook House has so many layers and so many family stories and connections to the life of its city—letters, ledgers, books, diaries, deeds, and billheads and receipts from local merchants going back to 1705—it is an almost bottomless repository of civic memory. The McCook brothers (mostly from Ohio) were famously numerous in their service to the Union cause during the Civil War. Recently the museum, a property of Connecticut Landmarks, personalized this aspect of the tour experience by incorporating excerpts from letters home during the war and accessorizing some of the rooms with war-related memorabilia.

The Shaw-Hudson House in Plainfield, Massachusetts, is a time capsule with a unique claim to fame. Built in 1833 as a home and office for Dr. Samuel Shaw (1790–1870), the house was occupied by several generations of descendants until it was bequeathed to the local Congregational Church for use as a community center and museum. Every cabinet, closet, shelf and drawer contains unique and compelling evidence of this family’s life and, by extension, the life of the town. The crown jewel of the house is Dr. Shaw’s medical office and the expansive material culture (including medicine bottles, implements, and furniture) and archives documenting not only his practice, but that of his father-in-law, Dr. Peter Bryant (1767–1820), with whom he apprenticed; Bryant was the father of poet and author William Cullen Bryant. Dr. Shaw retired from his medical practice in the 1850s. The office, scrupulously preserved by his descendants, looks like he has just stepped out for an errand; it may be the most authentic, untouched and evocative pre-Civil War medical setting in the country. And not only Dr. Shaw’s, but also the books Dr. Bryant began amassing in the 1780s—an astonishing medical library—including rare American imprints like the first (1812) and subsequent issues of the New England Journal of Medicine. As a microcosm documenting the evolving science and practice of medicine, this house is unrivaled.

Then there are the houses preserved as museums because the architecture is important. The National Trust for Historic Preservation is proud of its flagship Drayton Hall in Charleston, South Carolina, and the fact that it is presented unfurnished (Fig. 4). A monumental work of art, there isn’t an earlier (1738) or grander Palladian house in North America. But how do you make an empty house an outstanding visitor experience? By interweaving great stories, reading the architecture imaginatively, with a scholarly interpretation that is deep and engaging. The lives of the owners, the builders, the donor, and the enslaved workers emerge as guides “furnish” the rooms with stories that evoke the whole world of eighteenth-century patrimony and privilege, warts and all.

Another house shown in the raw is the Olson House in Cushing, Maine (Fig. 5). A property of the Farnsworth Art Museum, the contents of the house were entirely dispersed in the 1970s when it finally passed out of the family. The Olson House became famous as the subject of numerous works of art by Andrew Wyeth, including his 1948 painting Christina’s World. The Olson House became a symbol of a weatherworn, old New England in decline. Absent its furnishings, the untouched patina of walls, woodwork, and floors are enriched with photographic representations of works by Wyeth in the exact rooms he painted them in. Guides navigate this forlorn housescape, animating the spaces with stories that rekindle the Olsons and their long, complex relationship with a complex artist.

Of the countless community-based historical organizations in the country, some are housed in modern facilities, some in mansions, some in one-room school houses, former churches, town halls, and libraries. Most start small and make the best of what they have through volunteerism. In my hometown, Enfield, Connecticut, the historical society occupies a building that started life as a Congregational house of worship in 1771 (Fig. 6). In the 1840s, when the parish built a new meetinghouse, the building was modernized, its steeple removed and for half a century it functioned as a town hall. The town still owns the building and helps maintain it. About 1980, the Enfield Historical Society entered into a lease arrangement and the Old Town Hall, as it is known, is now a historical museum with a growing and increasingly fascinating collection of local treasures, including material from one of New England’s first and largest Shaker communities.

Osawatomie, Kansas, is a town of about 4,500, with a modest economy based on agriculture, small industry, tourism, and government. The Osawatomie State Hospital (psychiatric) is the town’s leading employer. Like Gettysburg, Osawatomie might not be remembered beyond Kansas but for an event that engraved its name in history. Two Presidents (Theodore Roosevelt and Barack Obama) delivered speeches there after the fact. August 30, 1856, was when the Battle of Osawatomie took place, where John Brown and a band of about forty free-state guerillas faced down a force of 250 pro-slavery “border ruffians.” Several freedom fighters were killed. It was an opening act on the road to the Civil War and it made John Brown famous. The Osawatomie History Museum, housed in a storefront connected to the old railroad depot, preserves and presents the town’s stories. It complements the nearby John Brown Memorial Park and Historical Museum operated by the Kansas Historical Society. Together they provide a rich, multifaceted experience that includes art, antiques, and memorabilia in service to an epic story.

There are so many astonishing house museums and historical societies—deeply evocative and unique in the way they bring the story of our nation home. If it was possible to round up 100 important objects and artworks from the 1001 best house museums and historical societies in America, it would be the greatest presentation of American art and cultural material ever brought before the public.

Historic preservation isn’t just about saving the built environment. It is also about content, stories, collections, and civic spirit so richly encapsulated in local organizations that often were doing the work of historic preservation before the birth of the modern preservation movement. Through the accessible history of local organizations, we learn and understand the context of the present and gain the critical thinking to aid in our path forward into the future. Caring and raising the bar of support and visibility is not only the least we as preservationists and those who care about cultural history can do; it’s the best we can do. The importance of having repositories that provide a sense of place and community are more needed now than ever before.

William Hosley is the principal of Terra Firma Northeast, Cultural Resource Development, and a marketing consultant. He has built an active community of like-minded preservationists at Housing Our History a Facebook community. All photography by the author unless noted otherwise.

This article was originally published in the Anniversary 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. This is an estimate. New data on the number of museums in America (gathered between 2009–2014) totals approximately 35,000; about half are history museums. The latter are not broken out by size, though 2010 estimates report that roughly fifty percent of history museums are considered “small,” with annual budgets under $250,000 USD; many even fall below half that amount. The new figures are in the Museum Universe Data File, compiled by the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS), an independent federal agency. The figures were “created from IMLS administrative records, commercial vendors, and the Department of the Treasury, which collects financial information for all active nonprofit organizations on an annual basis.” (See http://blog.imls.gov/?p=5464.) Previously, the estimated number “was based primarily on information from state museum associations.”

3. Jay D. Vogt, “The Kykuit II Summit: The Sustainability of Historic Sites,” History News (Autumn, 2007): 17–21. Part 1 of the summit was held at Kykuit in 2002; for an article about the summit see Gerald George, “Historic House Museum Malaise: A Conference Considers What’s Wrong,” History News (Autumn, 2002). Links to numerous articles on the subject are available in a pdf bibliography by Kendra Dillard, Director of Exhibitions, Capital District, California State Parks, for her talk at the AASLH 2011 Annual Meeting, which addressed “A New Beginning: Historic House Museums Adapt for the Future.” The topic continues in conferences, blogs, and other forum available online.

4. In Middlebury, Vermont, Sheldon’s cousin, Henry Sheldon, founded the Henry Sheldon Museum in 1881 as the Sheldon Art Museum, Archaeological and Historical Society. That year, Sheldon wrote “I have spent all my leisure the past year trying to benefit future generations by preserving the handiwork of the articles representing all the different occupations of the early pioneers which I have called a Museum. May those who many years hence look at these articles take as much pleasure in doing so as I have in collecting them.”