Early American Trade Cards

Trade cards, an early form of advertising by tradesmen and shopkeepers, originated in England in the 1600s and appeared in the colonies by the 1720s. Eighteenth-century trade cards provided the seller’s name, location, and products for sale, often with ornate engravings of wares, shop signs, storefronts, or interiors. Contemporaneously known as tradesmen’s or shopkeepers’ bills, trade cards, as they are now commonly called, occasionally doubled as invoices, while those with the words “Bought of” began life as billheads, which served as proof of delivery. Highlighted here are a number of examples from Winterthur’s collection.

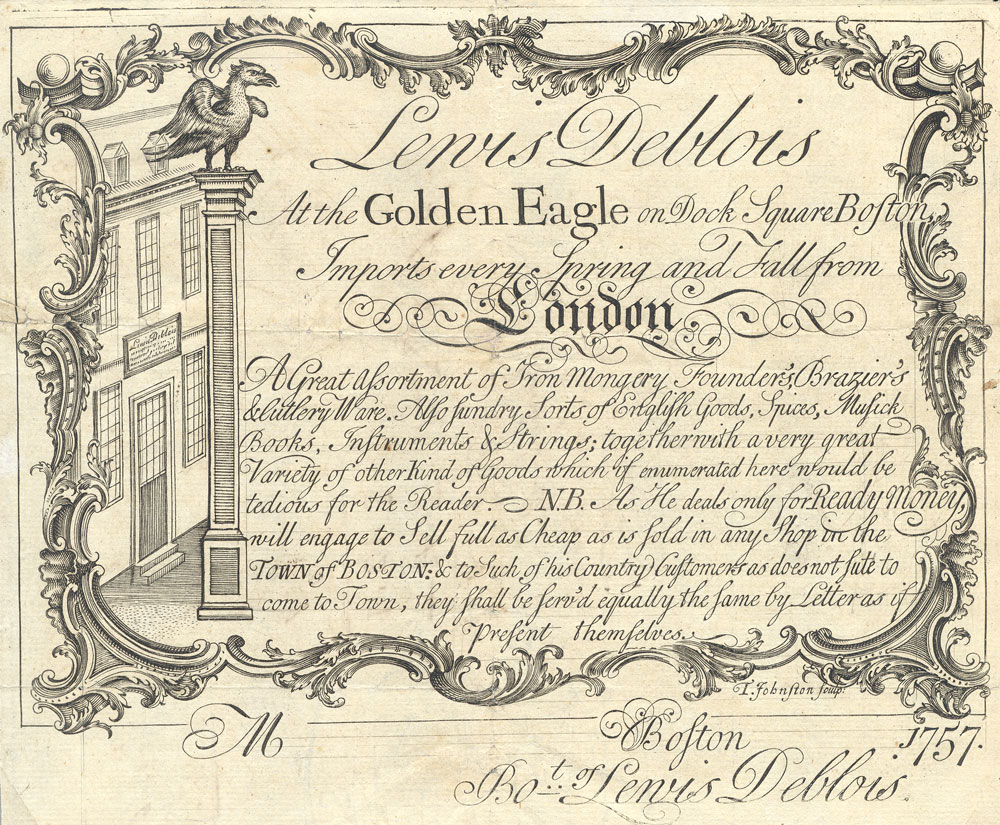

Boston merchant Lewis Deblois was a member of a prominent French Huguenot family (Fig. 1). In business with his brother Gilbert for nearly ten years, by 1757 he was operating his own shop in the prime commercial center of Dock Square, near the waterfront.1 He imported a multitude of items twice a year from London for his customers in town and in the “country,” suggesting not only the colonists’ desire for fancy goods from abroad but also the presence of distribution networks and the reach of his business connections. Deblois’ ties to England never diminished; in 1776 he evacuated to Halifax in response to the Revolution and later sailed to England, where he died in 1799 at age seventy-one.

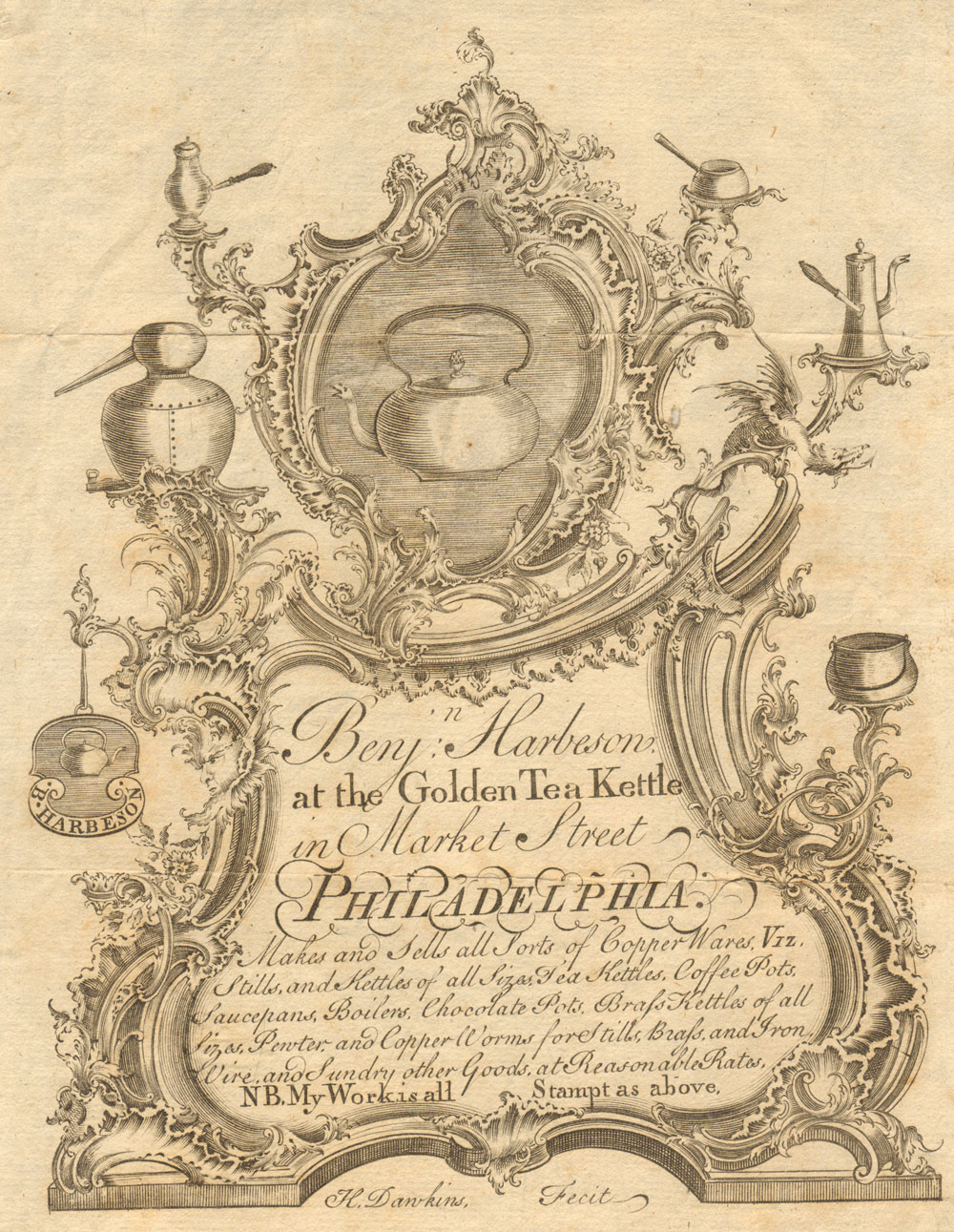

The elaborate design of Philadelphia coppersmith Benjamin Harbeson Sr.’s trade card (Fig. 2), with its cartouches, copper wares, and shop sign, leads us to a fascinating character, Henry Dawkins. The English-born engraver first trained as a silversmith. He arrived in New York City around 1753, and worked there and in Philadelphia until the late 1780s. Dawkins copied the design for Harbeson’s trade card from several English examples, one of which was Edward Warner’s label for razor-maker Henry Patten.2 Besides pirating this design, Dawkins was arrested in 1776 for counterfeiting paper currency, a logical sideline for owners of copper plates. Full details of the story are unknown, but in 1777, he was possibly freed by the British after they gained possession of White Plains, where he was incarcerated, or he may have escaped. Suffering no permanent damage from the disgrace, Dawkins was soon engraving bills of credit for the Continental Congress.

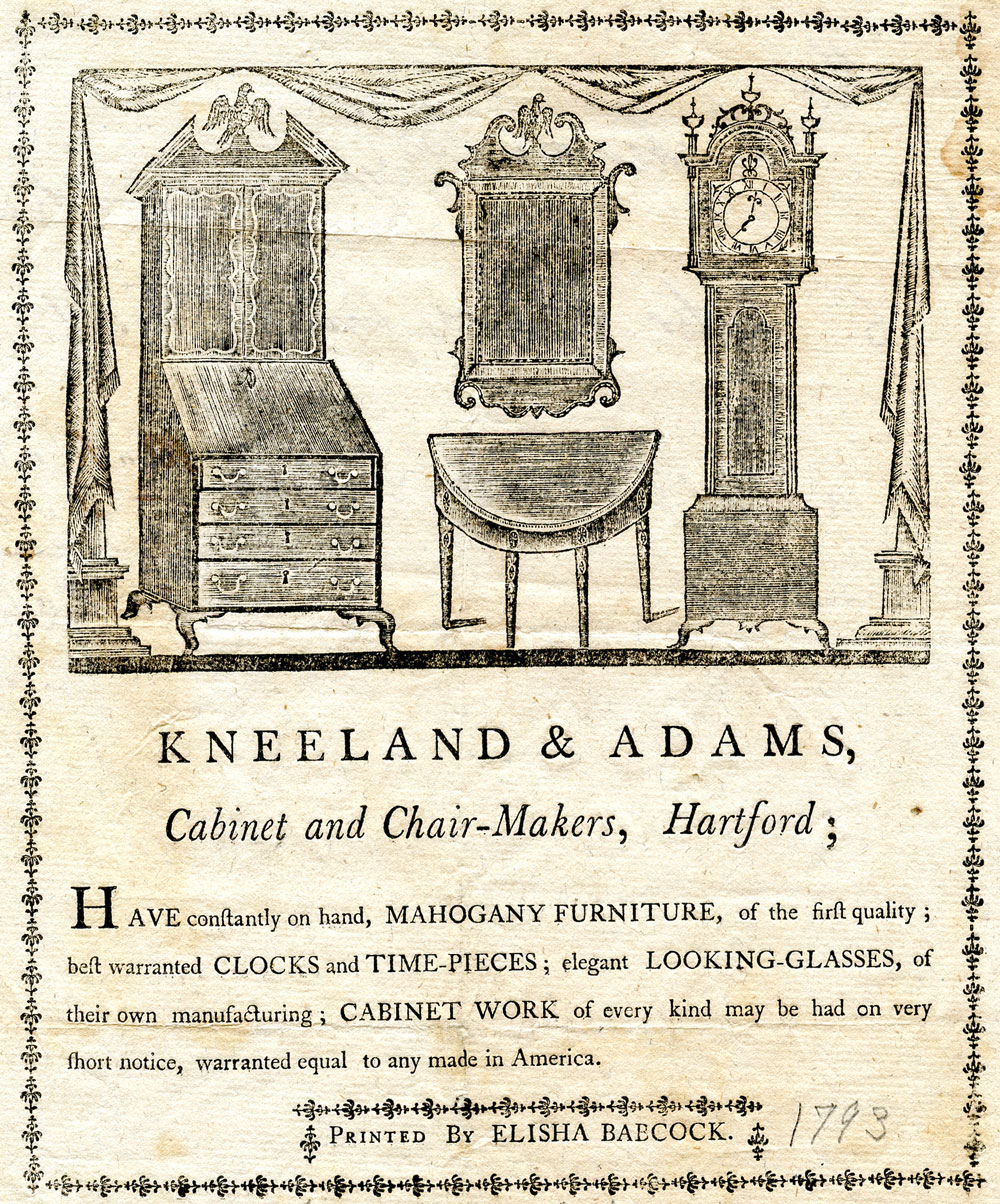

In contrast to the rococo flourishes of the two previous cards, the trade card of cabinetmakers Kneeland and Adams (Fig. 3) demonstrates a classical restraint in its simple border framing their wares, two of which sport eagles to represent the new republic. The partnership of Hartford cabinetmakers Samuel Kneeland and Lemuel Adams lasted only from September 1792 to March 1793, yet they secured a notable commission to make furniture for the State House. While labels were sometimes glued to furniture where remnants found today can aid in authentication, this item was not attached due to its size. Instead it was used as an invoice for six parlor chairs and a stove frame and saved with the chairs by the original owner’s family. In 1967, Winterthur acquired both the chairs and the card, a happy marriage of artifact and documentation.4

The mid-1790s was an exciting time for Raphaelle and Rembrandt Peale, sons of Philadelphia artist Charles Willson Peale, and painters in their own right. Beginning in 1794, they jointly sought portrait commissions; with Raphaelle painting miniatures and Rembrandt full-size likenesses (Fig. 4). In 1795 and 1796, they spent several months in Charleston and Baltimore seeking sitters and exhibiting copies of their father’s portraits of patriots. The year 1795 also marked their professional debuts at an art exhibition and Rembrandt’s first portrait of George Washington. Parting ways after a few years, Raphaelle became known for his still life and trompe l’oeil paintings and scientific writings, and Rembrandt for portraits of famous figures and his involvement in early art academies and museums.

Now highly collectible as engraved prints, trade cards also provide valuable insights into printing processes, stylistic influences, product availability, economic history, and everyday life in America. You can see more advertising ephemera from the Winterthur Library online at http://content.winterthur.org:2011/cdm/.

-----

Jeanne Solensky is librarian in the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available on Incollect. They are also gathered together at www.Winterthur.org.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. The Primer articles are regular contributions from the curators and conservators at Winterthur Museum. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

2. Examples of Henry Patten’s trade card exist in several repositories, among them the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Guildhall Library.

3. Notices of the formation and dissolution of their partnership were placed in the weekly newspaper American Mercury, published by Elisha Babcock, printer of their card.

4. Winterthur accession numbers 1967.0151.001–.006.